While COVID-19 spreads across the United States, the best thing that most of us can do is self-quarantine. Companies across the country have closed their offices so people can work safely from home. K-12 schools, from San Francisco to New York City, have shuttered to thwart the spread of infection. We can expect more school districts to follow suit, as the CDC now recommends schools close and stay closed for the next eight weeks to protect our population; President Trump has recommended closing schools, too.

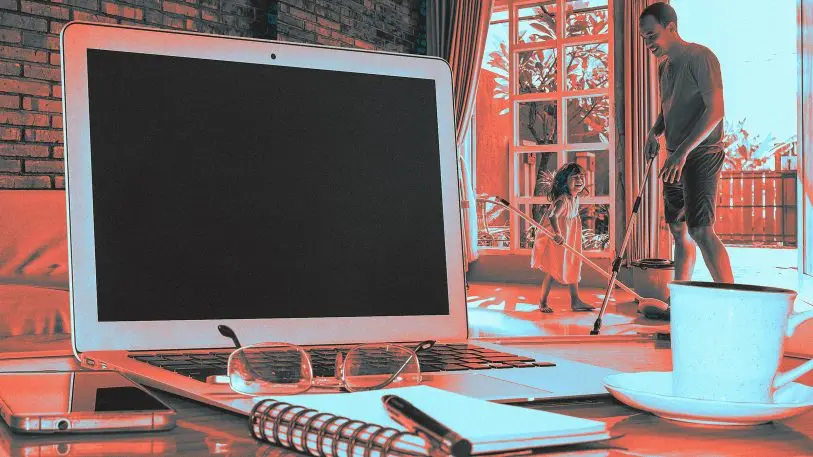

That means means the 57 million children in our educational system could soon be home all day, in the same houses and apartments as their working parents. In the United States, where more than half of families have a pair of working parents, and 23% are headed by single moms, this is an unprecedented crisis. How do we watch and educate our children while also clocking in the current 47-hour workweek?

Here’s a proposal: We don’t.

I’m not saying we go on strike. (Though companies that can afford it might consider adding a few months of paid leave for employees.) We should keep working, but work a whole lot less so that we can support our children a whole lot more. And that applies to everyone, with kids or without.

I recognize that I’m making this argument from a position of privilege. I’m a salaried, staff writer, not working hourly or as a freelancer. My checks will keep coming even if my output temporarily dips. Meanwhile, more than half of full-time employees in the U.S. are hourly. Nearly 2 million of those employees make minimum wage or less. Already, many of these jobs are being cut.

Which is all the more reason that we need to ask less of ourselves as professionals and less of each other as coworkers. It’s time to phone it in, literally and figuratively, to both protect our world and nurture the next generation.

The rise of omnipresent productivity has already squeezed us dry

It’s no secret that we live in a nonstop work economy, which has both necessitated and enabled new tools to make sure we can and do work all the time. Over the past decade, omnipresent internet connections, Slack, Office 365, Google Docs, and Zoom have made it easier than ever to collaborate with peers from thousands of miles away . . . or just from home! Telecommuting grew 159% between 2005 and 2017, but taking a meeting in sweatpants doesn’t change the fact that a third of Americans routinely work more than 45 hours a week, and nearly 10 million people work more than 60. (Note that Americans work about an hour longer per day than people do in Europe.)

In the United States, we work about 8% more hours than we did in the 1978. Doesn’t sound like that much, right? It’s actually about 150 hours, or three full weeks of work added to each year, by back-of-napkin math.

Over this span, all those aforementioned tools really did make us better employees. We’re six times as productive as we were in the 1970s, even though we only make 11.6% more for the work. This capitalist paradox has been referred to as the “The Productivity-Pay Gap.” Employee compensation hasn’t grown alongside corporate profits.

What does this have to do with COVID-19? You hardly need to go full Bernie Sanders to recognize that we are beholden to a life of too much work, reinforced by companies that profit off of enabling that work. That arrangement is not really working for our society on any given Monday—90% of Americans report being at least somewhat burned out at work—but it is entirely unsustainable in a world where tens of millions of Americans are working from home while watching their children.

For working-class parents, it’s too much. I see this already with my fellow parents at Fast Company, each of whom is hustling to invent some balance of work-parenting over the coming weeks—which includes watching kids in shifts with their spouse, working hours into midnight, or shelling out money for tutors or babysitters. These are unsustainable practices that could make our entirely justified anxiety even worse.

No helping hands means we use our own

The other reality is that, even as we face the earliest days of this pandemic, most working parents have already lost many of the resources we rely upon to maintain our productivity. Every parent relies on a support system to do their job well.

Those missing helping hands vary wildly in nature—from Amazon Prime food deliveries and Walmart grocery pickup (both of which are currently down in my local Chicago suburbs) to grandparents stepping in to help watch our children (and one in three parents relies upon their parents to do just that). In many areas, senior citizens have been instructed to quarantine themselves for their own health. Who watches our kids then? We do.

Closed schools mean more than children being on vacation for a few months. Many schools have already decided that the weeks and months missed under this “Act of God” classification will not be made up at the end of the year. They’ve shared lesson plans, apps, and other educational resources for parents to run themselves at home to map up any educational gaps. Teaching, needless to say, is a full-time job—and it’s a separate full-time job from parenting, which is a separate full-time job from whatever you might do to get that check every two weeks.

Heard this from a friend: “I’ve homeschooled my son for 30 minutes and I’ve come to the conclusion that all teachers should be paid a million dollars.”

— Steve Gilbert (@SteveGilbertMLB) March 16, 2020

Put differently, it’s a lot to ask parents to teach their own children, but it’s even more to ask parents to work instead of teaching their own children. Free public schools are one of the great accomplishments of modern civilization, so much so that lawmakers were prescient enough to make school a legal obligation for children to attend. Last I checked, there was no law about checking notifications from my manager on Slack.

I certainly don’t need to tell you what matters more

But more than getting education, or entertainment, or even just our attention, our children deserve to feel safe and secure. The coronavirus is an adult’s problem, and it’s spread as far as it has largely due to our own failings of policy and infrastructure. We are at grave risk of losing much of our oldest generation, while traumatizing much of our youngest generation. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Health and others, has issued a warning around the COVID-19 pandemic, and recommends we keep kids in a routine, communicate with them, and serve as role models through the course of this pandemic. This is active parenting in the strictest sense, and it’s the most important thing that many of us can actually do in a world where we’re supposed to just stay home.

And if parents are working less, everyone should be working less—and for many of the same reasons. Employers need to adjust their expectations of all employees because it’s the right thing to do in the face of a national emergency and global pandemic. Everyone needs to take care of themselves and their families right now, whatever that family may look like—roommates, dogs, or neighbors.

In the next month, our country is going to face incredible loss to this virus, just as we’ve seen previewed so horrifically around the globe. This is not a moment for business as usual, for bringing smartphones to the dinner table and working into the late hours of the night as part of some fealty to corporate America. We need to slow our companies down—whether they like it or not.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.