In late 2019, Dyson pulled the plug on its most ambitious project ever: an electric car that the tech company built from the ground up. The car itself was reported to have been largely completed; everything from the drivetrain to the windshield wiper motors were powered by Dyson technology. Four years in the making, the project had $2.5 billion in promised investments from James Dyson himself.

But building cars is an expensive business, and electric cars, only more so. As Dyson explained to Fast Company in an interview on the eve of the company’s latest product launch, a new flat iron, it was only in the 11th hour of the car project that he realized the truth: He couldn’t sell his electric car and cut a profit.

The same can be said of Tesla, which lost $862 million last year, but Tesla is a publicly traded company that just raised another $2 billion as of this year to cover its financial shortcomings. Dyson is a private, family-owned business, and James Dyson tells us that he didn’t want to take external investment.

But just because he’s given up on electric cars doesn’t mean that he’s given up on electric transportation. The micro mobility market, which includes electric scooters, bikes, and new forms of transit entirely, represents what’s estimated to be a $300 billion to $500 billion business by 2030. When we asked Dyson if he imagined the company could compete in this industry, he didn’t hesitate. “You know electric motors are one of our big [products] . . . we made a very good electric motor for our electric car, and we’re developing solid state batteries,” he says. “So we could get into some form of transportation—I wouldn’t doubt it at all—particularly when we have a very efficient battery.”

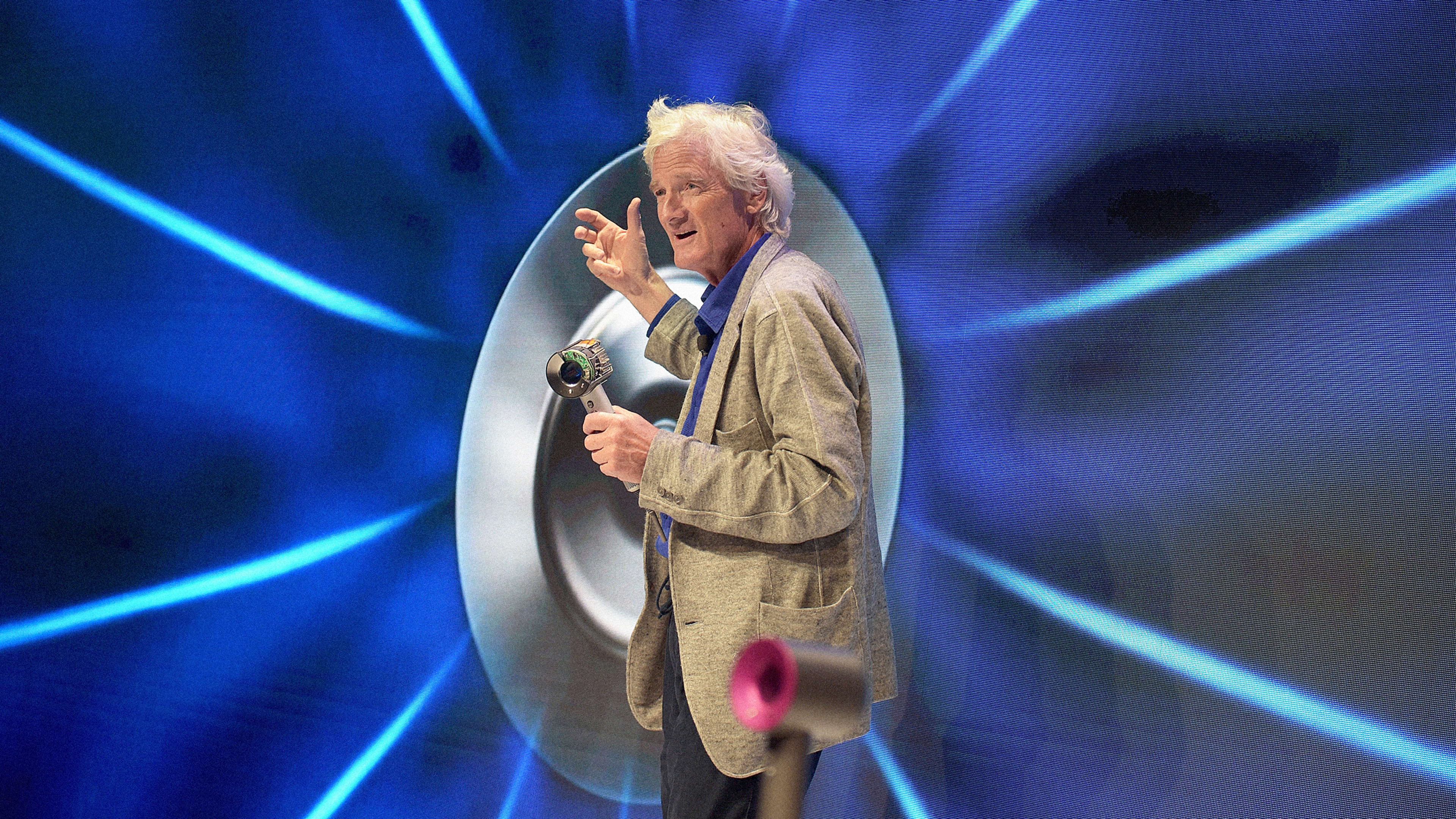

Below, James Dyson discusses his company’s new hair straightener, lifts the curtain on the company’s product development process, and yes, has more to say about his dream for a clean electric vehicle.

Fast Company: So Dyson has this incredible engineering and design heritage. I’m curious, how do their inventions become a product like this new flat iron [released earlier this week]? Is the product born from market insights? You see the market potential and just think, we can do this better—go at it, development team?

James Dyson: We never think of the market for the product. It’s not something that guides us. We look for a problem in the product, and then we go to solve the problem. Hand dryers aren’t a particularly big market compared to hair dryers or vacuum cleaners, but that didn’t stop us from wanting to make a hand dryer. Having an interesting technology for products decides what we do, whether the market is small or big.

FC: Isn’t picking a new product to develop about more than problem-solving, though? Because your company has the talent to solve problems for just about any product in the world. Take the fan, for instance. How did you choose to get into fans? The fan eventually became an air purifier, and air conditioner, and all sorts of other combo products. But it started as a simple fan. Did you know there would be this long tail to the product category all along?

JD: The fan was from the Air Multiplier idea, which came about from something else we were developing that didn’t work as well as we wanted it to. Again, I didn’t go and look at the size of the fan market or anything, but thought we have a really good fan to make.

We have confidence, maybe misplaced, we can go on and keep improving technology. By the time we launch it, we’re onto the replacement because we’ve already thought of it. Fortunately, we developed the fan, so it became a heater, and then purifier, then a heater and cooler and purifier and humidifier all in one! We’re creating a real market and solving real problems. Although the fan market is comparatively small . . . it’s become more.

FC: You really didn’t plan this whole product category at launch?

JD: In the case of the fan, we were just thinking in terms of a fan. I happened to launch it in NYC—in the winter. [laughs] And sitting in the back of a yellow taxi during the launch, and I talk to my chief engineer Pete Gammack, and I said, “We need a heater.”

FC: A lot of startups aim to raise money, go IPO, and cash out—and then they build a business that answers to Wall Street instead of actually innovating. Even Apple is beholden to shareholders every quarter. Do you ever wonder how life would be different if Dyson were a public company, whether there are products you would or wouldn’t have made?

JD: I have to say, it’s not the sort of thing I like to imagine! But of course I occasionally imagine it. But the reason I wouldn’t [go public] is precisely what you say—we don’t have to worry about getting bigger or ever increasing our profits. It doesn’t need to be a worry for us. We don’t have to worry about what the market thinks of us. All our efforts can be geared toward making a better product. And if we make better product, then we survive. That’s how we think.

If we were a public company and we decided to do the car . . . we might have been able to raise money to do it and make it better. But on the other hand, our failure, or our decision to pull out of and not do it, doesn’t really matter to us. We can do that and we save ourselves from possible disaster, but we haven’t really lost anything aside from money.

We’re not charged by people because of the commercial failure. We just were able to make a rational decision: “Are we going to make money out of this? Probably not.” We can also afford to think very long-term on ideas that won’t come to the market for 10 to 15 years.

FC: With the car, if you weren’t answering to anyone but your own family, I’d actually wonder the opposite: Did you consider, not abandoning the project rationally, but staying with it passionately?

JD: I developed something that collected diesel exhaust years ago. I have a passion for producing a clean car that doesn’t pollute. That’s a real thing that really mattered to me. That was part of the drive to make an electric car.

The trouble is you have to see what’s happening in the marketplace. Existing car manufacturers making an electric car, in the EU particularly, they have to have exhaust emissions across their range of cars. It’s fine to lose $12,000 to $15,000 making an electric car, because it balances out with big SUVs. So they can afford to lose a lot of money on the electric car. But you know, we couldn’t afford to get into that sort of market.

FC: The scale of revenue just wasn’t there for Dyson to make that bet.

JD: Yes . . . they have an advantage to offset an electric car . . . but that only became apparent as we were developing it. It took us about four years, and towards the end, we started realizing . . . it would be a lot more expensive than [competitors’ cars].

FC: Could you imagine building a smaller personal transportation device—companies like Segway are prepping for a complete second act, as Uber and Lyft imagine a new wave of micro mobility in cities.

JD: You know electric motors are one of our big [products] . . . we made a very good electric motor for our electric car, and we’re developing solid state batteries. So we could get into some form of transportation—I wouldn’t doubt it at all—particularly when we have a very efficient battery.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.