“If you assume any rate of improvement at all, then games will be indistinguishable from reality, or civilization will end. One of those two things will occur,” Elon Musk told Joe Rogan during his infamous pot-smoking podcast appearance in September 2018. “Therefore, we are most likely in a simulation, because we exist . . . . I think most likely—this is just about probability—there are many, many simulations. You might as well call them reality, or you could call them multiverse.”

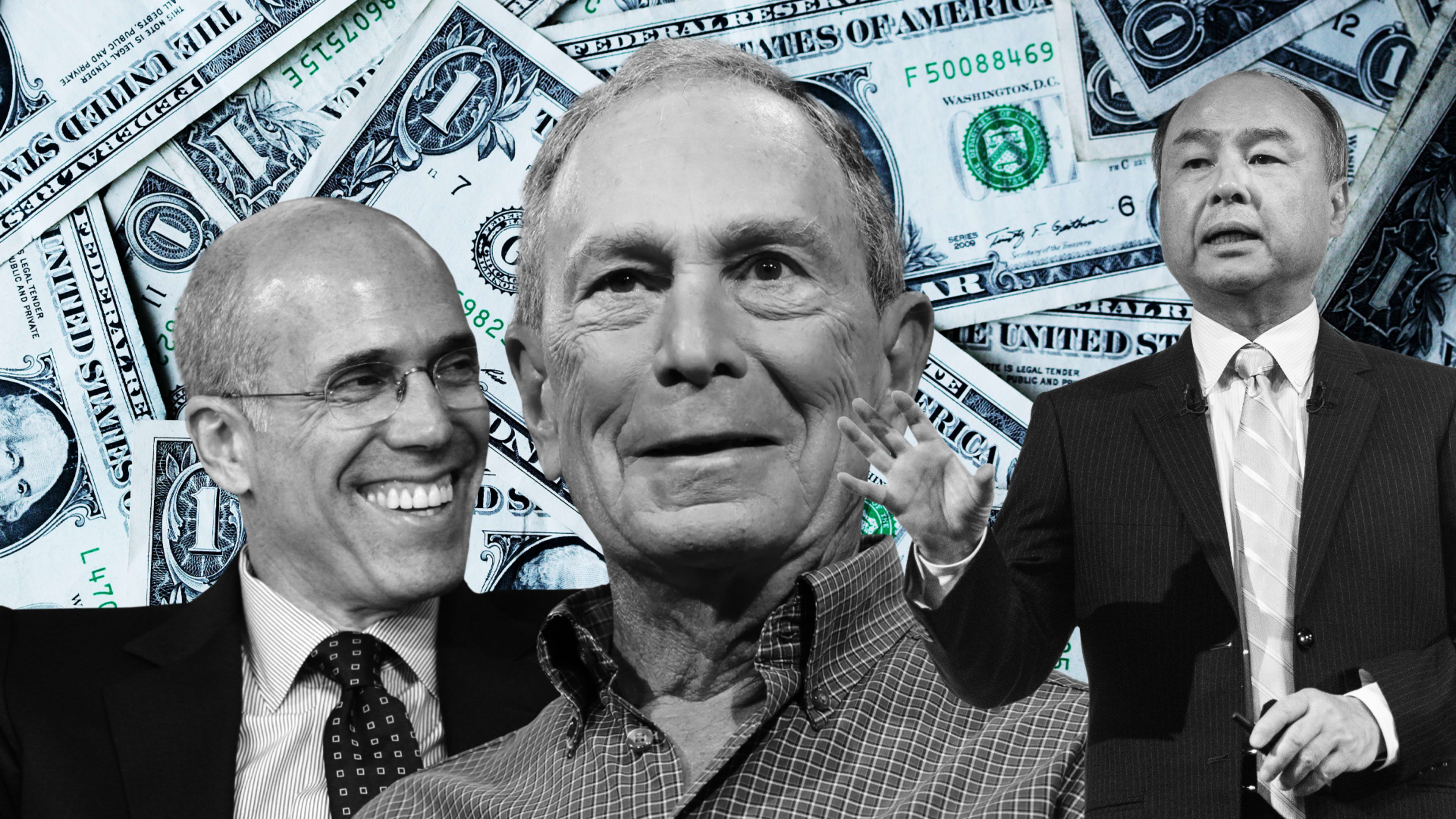

I scoffed at Musk’s comments then, but sometime during the January 14 presidential debate, when it became clear that Mike Bloomberg, the billionaire mayor turned 2020 candidate, had hired someone to write weird Twitter posts to steal attention from the candidates onstage, I realized that I should not have doubted Musk.

Bloomberg was living in a simulation.

But it wasn’t a video game.

No, he was living in a simulation of the 1985 movie Brewster’s Millions. It was the most plausible explanation I could muster for his spending behavior.

As I’d come to realize, he was not alone.

The genius premise of Brewster’s Millions

Brewster’s Millions is a Hollywood plot so surefire that it’s been made into a movie half-a-dozen times, going all the way back to 1914. The 1985 version starring Richard Pryor and John Candy, though, is the most recent (and the only one that’s readily available). Originally conceived by the early 20th Century novelist George Barr McCutcheon, the plot outline is deliciously simple: When our protagonist Brewster (their given name has been everything from Jack to Montgomery to Polly—yes, there was a Miss Brewster’s Millions) inherits a significant sum of money from a long-lost relative, there’s a catch: Brewster has to spend it all in 30 days. If he or she does, they’ll receive 10 times the money. That’s their true inheritance. But wait, there are more catches: They can’t just give the money away or destroy things of value, and they cannot tell a soul why they’re spending the way they are for a month. If they fail in any way, they get nothing.

Hijinks ensue!

In the 1985 version, Pryor plays Montgomery “Monty” Brewster, an aging minor-leaguer still dreaming of pitching in the major leagues. He thinks he’s being followed by a pro scout, but turns out he’s a bounty hunter hired by the firm managing his great uncle’s estate. His uncle explains the rules via a filmed message made before his death, telling Brewster, “I’m going to teach you to hate spending money. I’m going to make you so sick of spending money that the mere sight of it is going to make you want to throw up.”

Mike 2020

The parallels between the plot of the movie and the surreal winter of Mike Bloomberg trying to buy the presidency are perhaps the most remarkable evidence of the Brewster’s Millions simulation.

An hour into the movie, and about halfway through his quest to spend the $30 million, Brewster runs into the rich-guy problem of having his money make even more money, thus putting him in an even-deeper hole to spend everything he has by his deadline. That’s when he flips on the TV to hear a local news commentator say, “With less than two weeks remaining until the election this station is sorry to report that it finds itself unable to endorse either of the candidates for Mayor of New York . . . . In the view of this station, the only issue being raised by the Heller-Salvino debate is whether the City of New York is for sale and just how much slush money it’ll take to buy it.”

Of course! What better way to drain a bank vault of cash than to launch a self-funded run for office? (Tom Steyer can tell you that. Another Brewster’s Millions, to be sure.) Almost immediately after Brewster enters the mayoralty campaign, he’s plastered his ads everywhere encouraging people to vote “none of the above.” His spending is so omnipresent that the film’s villains lament that Brewster is not only buying prime time on every station, but he’s buying ads in all 50 states, just in case there’s a New Yorker on vacation who might see it.

Bloomberg bought a 60-second Super Bowl ad. He bought Instagram influencers. He advertised during his second debate appearance last week, which was weird! He cut an ad with dogs endorsing him. He bought three minutes of prime time on two networks on Sunday night to address the nation about coronavirus in front of a blurry backdrop that sure made it seem a little bit like he was already president and living in the White House and we just missed it while in our own simulations. On last week’s episode of The Underculture, comedian and impressionist James Adomian’s podcast, he satirized the Bloomberg ad strategy by having him buy ad time within his own ad.

The former New York City Mayor packed campaign events with lavish catering, offering potential voters (and the media) BBQ sliders and bottomless caipirinha pitchers. When Brewster does the exact same thing in the movie, he whips a crowd into a raucous call-and-response by saying, “I want to ask a question: Who’s buying the booze?”

The response: “You are!”

“Who’s buying the food?”

“You are!”

“And who’s trying to buy your vote?”

“You are!”

In hindsight, perhaps the Bloomberg campaign’s greatest failing was that it was too subtle.

A vision with the Vision Fund

Now that I’d been blackpilled, I saw Brewster’s Millions simulations everywhere I looked.

SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son had shocked the world by raising almost $100 billion in 2016 for a Vision Fund to usher in the future of technology for the next 300 years, and then investing it all in just three.

Had to be a Brewster’s Millions.

Early on in the movie, Brewster reveals his insecurities about his spree when he says, “Excuse my expression, but you think I’m a real asshole, don’t you? A country bumpkin that flashes his money around like some big shot.” That’s how other VCs and any entrepreneurs who didn’t receive a Vision Fund investment felt as they watched Son blow up traditional venture investing, buying up stakes in every global ride-hailing platform, for example.

The media, though, loves Brewster’s antics, showering him with attention and calling his behavior merely “eccentric.”

Upon receiving his $30 million, Brewster is quickly inundated by people wanting him to invest in their projects. This culminates in a scene where a guy explains to him that a glass of water costs $5 in the desert in the Middle East but we have huge icebergs at the North Pole. So what if we cut a chunk out of a big iceberg, install an outboard motor, and drive it down to the desert? “Brewster’s Berg to Mecca,” the pitchman says.

“If I gave you $1 million for this iceberg thing,” Brewster asks, “would that be enough?” The entrepreneur can hardly believe his good fortune in receiving far more than he expected, and Brewster, for his part, exclaims, “I just bought an iceberg!”

The Vision Fund’s investments have been so dizzying and multitudinous, are we 100% sure that it hasn’t invested in an iceberg mobility startup?

Son’s bet was that his unprecedented investments would help his startups succeed by making them inevitable, but doesn’t the Vision Fund make more sense if you think that Son’s Uncle Rupert promised him his $1 trillion fortune if he could lose $100 billion without telling anyone the real reason why he was investing in dog walkers and robotic pizza startups?

Cuckoo for Quibi

There was no turning back now. You’ve heard people say that they’ve been Jokerfied? I’ve been Brewsterfied.

The other head-scratcher barreling right toward us is the April 2020 launch of Quibi, the streaming-video startup with Hollywood production values but a 10-minute time limit per episode. These have been dubbed “quick bites” of content, or Quibis, by their creator, the longtime Hollywood impresario Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Katzenberg is also Monty Brewster. He’s taking two or three breakfast meetings a day. There isn’t a ritzy A-list conference locale in the last year—from Austin to Aspen to Las Vegas—where he and Quibi CEO Meg Whitman haven’t appeared on stage. Every star in Hollywood now appears to have a Quibi deal. He, too, bought ad time on the Super Bowl two months before Quibi existed.

In the movie, Brewster spends a significant sum arranging for a three-inning exhibition between his Hackensack Bulls and the New York Yankees, a quick bite of baseball, if you will. He spiffs up the stadium, buys everyone new uniforms, and rents luxury apartments for all his teammates while they train for the big game. Spoiler alert: The minor-league team still loses.

Although one can argue that Hollywood is built on the very idea of spending outrageous sums of money with no logic or reason, there’s something special about trying to succeed in high-quality, short-form mobile video. The last startup I can think of built on this premise was called Amp’d Mobile in the mid-2000s, and it burned through $360 million in 36 months before going bankrupt. Was it a Brewster’s Millions? Probably! Even Katzenberg himself tried this same idea 20 years ago with a startup called Pop.com, which imploded in the dot-com crash. Was Pop.com a Brewster’s Millions? Sure, why not?

Think about it this way: If Quibi succeeds, it’ll only make it that much harder for Katzenberg to lose the $1.75 billion he’s raised to get the $17.5 billion awaiting him.

It’s Brewster’s world

McCutcheon’s original novel is described as a comic fantasy, and in the early 1900s, I bet it was!

In 2020, though, Brewster’s Millions is reality. Modern startup culture can be neatly summarized as spending tremendous amounts of cash, as quickly as possible, in the hopes of unlocking 10 times the value. And what’s the harm when you’re playing with house money? Today’s world is awash in capital, closely held by a handful of billionaires with an insatiable appetite for pricey ego trips. With about $60 billion to his name, Michael Bloomberg can make back the $600 million he spent on his campaign with one good day in the stock market.

Such vast sums of money are immaterial to those who have them, and almost incomprehensible to those who don’t. In the 1985 Brewster’s Millions, the prim accountant character tracking Brewster’s receipts (played in this version by Lonette McKee) is aghast as she thinks about how this money being wasted could be better spent helping people in need.

Toward the end of the movie, with Brewster having spent what he thinks is his last $38,000 on a party, he invites the accountant, whom he’s now in love with, to join him at the soiree. “If you want to know the truth,” she says, “I don’t see what you could possibly be celebrating unless you think it’s okay to squander $30 million.”

“I don’t,” Brewster replies. “I just think maybe it was just a phase I was going through. Listen, tomorrow, things will be different. I won’t be like this anymore.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.