Designer Rebecca Minkoff and her brother Uri are well known for incorporating new technologies into the fashion company they’ve built together. They’re at it again with the launch of their newest brand, a kid’s label called Little Minkoff.

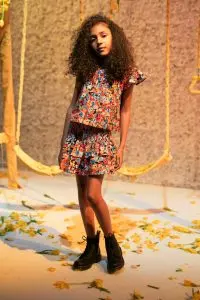

This time, the tech isn’t particularly obvious to customers: The collection of ruffle skirts, moto jackets, and jogger pants for kids ages 5 to 12 has fun, spunky patterns, like tie-dye and leopard prints—teeny versions of what you might expect from the adult Rebecca Minkoff collection. But behind the scenes, the Minkoffs worked with a tech platform called Resonance, which allows them to trace each garment as it moves through the supply chain to ensure that it is made using eco-friendly materials and ethical labor practices. The products are also made on demand in a factory in the Dominican Republic, which cuts down on excess inventory and wasted materials.

Rebecca had been dreaming up Little Minkoff for several years. As the mother of three young children, she found that her own kids wanted to wear clothes that she designed. The Rebecca Minkoff brand launched 15 years ago, so many of the women who first got to know the brand in their teens or early twenties now have children of their own as well. An environmentally minded collection was a must. “Many parents are so concerned about toxins in food and in the environment,” Rebecca says. “I wanted to make sure that there weren’t toxins in the clothes we made and that the manufacturing process produced as little waste as possible.”

Uri found a solution in Resonance, a blockchain startup cofounded Christian Gheorghe and Lawrence Lenihan, who collectively have decades of experience in the tech and apparel industries. Resonance has built an apparel supply chain all the way down to the fibers: The company owns its own factory, and hires each of the workers in these facilities. This means that Resonance has more control over the process than most apparel companies on the market.

Resonance says it uses largely biodegradable materials, like silk, linen, and cotton, and works with suppliers that minimize the water and chemicals used in the production process. Resonance also uses a digital printing technology that reduces the amount of ink used in clothing compared with traditional fabric dying. (And, for that matter, it only uses nontoxic dyes, which decreases the amount of pollutants that end up in waterways and the chemicals that wind up in the final garments.)

One consequence of this process is that it enables factories to make products when a customer places an order because there is a digital blueprint of how the garment is made. The items are then shipped directly from the factory in the Dominican Republic to the customer’s house within a week. This has major implications for the design process. “Traditionally, designers need to work within a budget and place bets about how many of each item they should order for a given season,” Uri says. “But this way, they’re able to design whatever they want, without worrying about waste or excess inventory.” Ultimately, this is better for the brand’s bottom line because it’s not throwing away clothes or selling them at a discount, thereby possibly diluting the brand.

Uri says it made sense to roll out this new approach with Little Minkoff, since it’s an entirely new supply chain. It’s much harder to introduce transparency into an existing supply chain than to build one from scratch, but ultimately, the ambition is to shift all of the clothes and accessories produced by Rebecca Minkoff into a similar system. Last month, I reported about how the modern suiting label Theory has been working to trace its garments all the way back to their raw materials, but it’s a slow, laborious process that the brand must execute in stages. “Little Minkoff has been two years in the making,” Uri says. “It’s going to be more complicated to introduce it into our larger collection, which has its own supply chains, but that is absolutely our intention.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.