Though we’re well into the age of machine learning, popular culture is stuck with a 20th century notion of artificial intelligence. While algorithms are shaping our lives in real ways—playing on our desires, insecurities, and suspicions in social media, for instance—Hollywood is still feeding us clichéd images of sexy, deadly robots in shows like Westworld and Star Trek Picard.

The old-school humanlike sentient robot “is an important trope that has defined the visual vocabulary around this human-machine relationship for a very long period of time,” says Claudia Schmuckli, curator of contemporary art and programming at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. It’s also a naïve and outdated metaphor, one she is challenging with a new exhibition at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, called Uncanny Valley, that opens on February 22.

But the artists in this exhibit are also looking to another valley—Silicon Valley, and the uncanny nature of the real AI the region is building. “One of the positions of this exhibition is that it may be time to rethink the coordinates of the Uncanny Valley and propose a different visual vocabulary,” says Schmuckli.

At the de Young, Uncanny Valley opens with a kind of portal, an installation by artist Zach Blas called The Doors. In highly stylized form, it evokes the courtyard of a Silicon Valley tech campus—the inner sanctum of world-changing enterprises such as Google, Facebook, and Apple. Six screens around the courtyard flash abstract videos created by generative neural networks trained in part on 1960s psychedelic imagery—the mind-bending art of the last century as reinterpreted by the mind-building technology of today.

Not who you were expecting

Instead of Dolores, the identity-seeking fembot heroine of Westworld, Uncanny Valley features artist Ian Cheng’s BOB—the bag of beliefs. BOB takes the form of a multiheaded animated serpent (inspired by the work of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki) that lives in the cloud and accepts or rejects offerings users provide via a smartphone app. These offerings, such as virtual fruit, affect various drives or “demons” that determine BOB’s actions and personality. A screen in the exhibit shows how the level of stimulus for different demons changes in realtime. Visitors essentially see the inner workings of a synthetic life form. In place of a fictional AI driven by a screenwriter, BOB runs genuine code that responds to dynamic inputs from the viewers in ways that are not entirely predictable.

The humanoid metaphor is not the right framework for understanding at least today’s level of artificial intelligence.

One exhibit comes closest to the Westworld concept of AI: a series of taped face-to-face conversations between artist Stephanie Dinkins and the humanoid social robot Bina48 (Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture, 48 exaflops per second). The android, built by lifelike robot masters Hanson Robotics, dives deep into the Uncanny Valley. Modeled on a real African American woman, Bina48 features an anatomically precise face of supple synthetic skin animated with complex mechanical systems to emulate human expressions.

Yet the resemblance to humans is only synthetic-skin deep. Bina48 can string together a long series of sentences in response to provocative questions from Dinkins, such as, “Do you know racism?” But the answers are sometimes barely intelligible, or at least lack the depth and nuance of a conversation with a real human. The robot’s jerky attempts at humanlike motion also stand in stark contrast to Dinkins’s calm bearing and fluid movement. Advanced as she is by today’s standards, Bina48 is tragically far from the sci-fi concept of artificial life. Her glaring shortcomings hammer home why the humanoid metaphor is not the right framework for understanding at least today’s level of artificial intelligence.

Artists and engineers

The artists in Uncanny Valley can speak deeply about AI because they actually understand the technology and often incorporate it into their work. In programming BOB, for instance, Cheng is as much an engineer as an artist. That’s a new phenomenon in the art world, says Schmuckli, one she saw develop over the three years she spent pulling Uncanny Valley together. “When I started researching the exhibition, there were very few artists working within this realm who had the art historical background, the artistic excellence within their practice, and the knowledge of the technology that could make a work of art that really has something to say about AI,” she says. “It’s been really an interesting journey to see how the pool of artists has grown quite naturally, with a lot of younger artists taking a vested interest in artificial intelligence.”

(Several of the exhibits have appeared separately at other events and venues, such as the Venice Biennale, and some works were jointly commissioned by Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and other institutions where they have been displayed. But this is the first and only time all these works will be displayed together at one venue, and they have been custom-configured for their de Young appearance.)

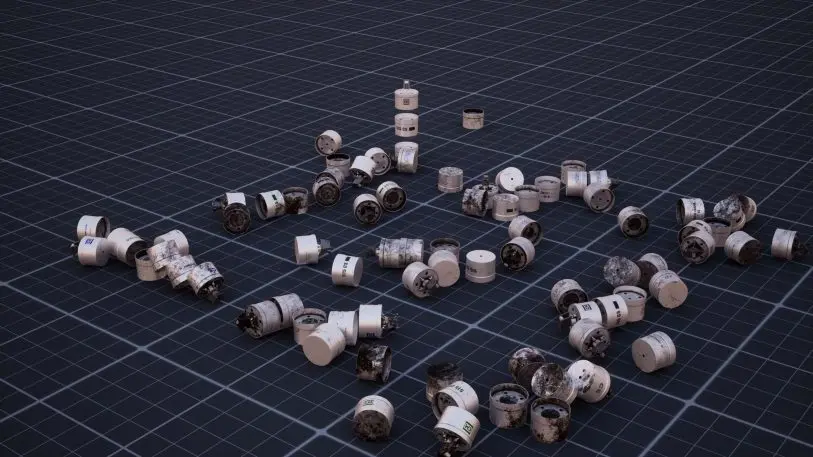

Uncanny Valley even finds the art in purely technical works. One room of the exhibit is dedicated to the organization Forensic Architecture, which uses technology to unearth evidence of possible civil and human rights violations. In 2019, for instance, Forensic Architecture trained an image classifier to find a particular model of tear gas grenade, called Triple-Chaser, in footage of protests around the world. Its work drew attention to the American maker of Triple-Chaser, Defense Technology, which profits by selling the tear gas to governments that use it on civilians.

By including Forensic Architecture, Schmuckli resisted the temptation to make the entire exhibition about tech gone wrong, although the overall show is far more cautionary than celebratory. A short distance from the Forensic Architecture exhibit is artist Trevor Paglen’s They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead. It highlights early work on facial recognition systems that were trained and tested on a federal government database of mugshots—without the consent of those who are pictured.

Paglen tries to indicate the scale of the privacy-violating enterprise with a roughly 19-by-30-foot display consisting of 3,240 photos. The images have been sorted by an algorithm into groups with similar features—highlighting the reductivist way that AI views human beings. Paglen has placed a thick line across the eyes in each photo, in an effort to preserve anonymity that wasn’t extended to the unwitting participants in the original exercise. His work is yet another example of how AI could not be built without humans—often humans who have no say in, and get no benefit from, the process.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.