The hospitality industry is in the process of introducing remote panic buttons in an effort to address the widespread issue of violence and sexual assault against hotel staff, and other sectors—including education and healthcare—may soon follow.

Thanks to the hard work of unions and the American Hotel & Lodging Association, over 20,000 hotel properties in Canada and the United States have committed to providing an estimated 1.2 million employees with Employee Safety Devices. Participating brands are currently in the process of rolling out a program that will require all housekeeping staff to carry a panic button device on them at all times. When activated, the devices provide precise location information to first responders. Early experiments have already proven them to be effective.

These efforts, however, are being undermined by the spread of low-quality versions of the technology that pose significant privacy and security risks to the people who carry them. Weak password protections and a lack of encryption leave users vulnerable to cyberattacks, which could render the devices unusable—or, worse, be used to invade hotel employees’ privacy. Furthermore, for the vast majority of hospitality workers who aren’t union members or aren’t employed by a major chain, there are few protections to limit their employers’ ability to abuse the technology, which in some cases has the ability to provide real-time data on the precise location of employees.

A decades-long fight

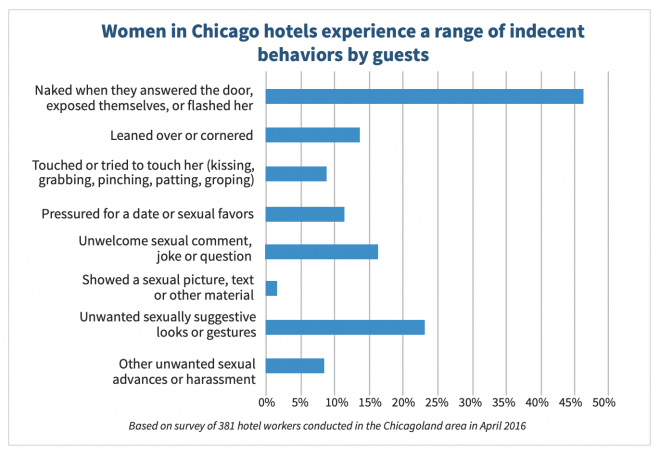

Sobering data makes clear why service-industry workers are eagerly turning to technology to help defend their personal safety. A July 2016 survey of 500 Chicago-based female hospitality workers by UNITE HERE—a labor union that represents roughly 300,000 hotel, food service, warehouse, and casino workers in Canada and the United States—found that 58% of hotel workers and 77% of casino workers have been sexually harassed by a guest. Nearly half have had guests answer the door naked or expose themselves, and nearly 15% have been cornered.

“We often hear reports of guests exposing themselves and housekeepers being subjected to harassment and assault, and we’ve been advocating for changes in the industry for over a decade now, going all the way back to 2011 with the Dominique Strauss-Kahn situation in New York,” explains Tiffany Ten Eyck, a spokesperson for UNITE HERE. (Its unusual name is an acronym based on the names of the two unions that merged to form it—the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees, or UNITE; and the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union, or HERE.)

“Something that sounds like such an exceptional and horrifying story is something we found was not exceptional among our membership, and it was sickening,” says Ten Eyck.

Since then, UNITE HERE has fought for greater protections for its members, participating in city- and state-level initiatives in locales such as Chicago, Seattle, New Jersey, and multiple areas in California. Those efforts recently appeared to have paid off, in part thanks to mounting pressure resulting from the #MeToo movement.

In September of 2018, the American Hotel & Lodging Association took up the cause and introduced the 5-Star Promise to its members, who represent more than 54,000 properties in North America. The organization described the initiative as “a pledge to provide hotel employees across the U.S. with employee safety devices (ESDs) and commit to enhanced policies, trainings and resources that together are aimed at enhancing hotel safety, including preventing and responding to sexual harassment and assault.”

When the initiative was first announced, the CEOs of a number of major hotel chains—including Hilton, Hyatt, IHG, Marriott, and Wyndham—joined the pledge. One year later, in October of 2019, the AHLA announced that there were a total of 56 participating brands, representing an estimated 20,000 properties and 1.2 million employees across the United States and Canada.

Taking a pledge is not the same thing as fulfilling it, and the details of rolling out ESDs are fraught with complications. “We’ve won these protections, but we haven’t seen the devices implemented in a lot of our hotels,” says Ten Eyck. “It really comes down to implementation; about what kinds of devices we’re putting into properties, if unions and workers have a voice in that. Those are the kinds of conversations we’re going to have this year.”

Safe but insecure

The discovery of vulnerabilities in certain versions of this technology may pose a potential challenge to the unions’ progress. In recent years, a range of vulnerabilities have been discovered in similar devices designed to be used as panic buttons for the elderly and for parents as a way to watch over their children. These mostly unresolved issues may soon spread to the hotel industry as well, as thousands of properties prepare to deploy similar devices to millions of hotel staff in North America and around the world.

In the fall of last year, a cybersecurity expert named Martin Hron was curious to see how difficult it would be to hack into a location tracker purchased by a colleague for his child.

Martin Hron, Avast SecurityIt’s not a problem of the security of one particular vendor, but a problem of the supply chain.”

But it wasn’t just a lack of encryption that compromised the device’s security. As Hron continued to analyze the Chinese-made GPS tracker, he discovered even more vulnerabilities.

“Usually these devices come preprogrammed with a default password, which is usually ‘123456,’” he says, adding that users have the ability to change the default password. “You can send an SMS message to a tracker, which instructs the tracker to send you a GPS coordinate back, and you only need to provide the password in that SMS, and usually the password is ‘123456,’ or something similar.”

Hron also discovered that the software powering the tracker was hosted on a cloud-based service, which it used to communicate with a mobile application. But the cloud software didn’t require any authorization. A hacker could connect to the service and “instruct any tracker in the world to do things,” he explains.

Among the vulnerabilities a hacker could exploit are the ability to see the real-time location of users and to gain access to built-in microphones and cameras, which are popular in versions of the product that are used to monitor children and the elderly. (At this point in time, it doesn’t appear that the hospitality industry intends to incorporate voice and video capabilities into employee safety devices.)

While Hron discovered these flaws in the T8 Mini GPS trackers created by Shenzhen i365 Tech, the company sells a range of similar products under a variety of different brand names all over the world. Overall, the vulnerabilities he discovered apply to 30 models, totalling more than 600,000 trackers sold worldwide. The various models include location-services products designed and sold for children, the elderly, and car fleets, as well as panic buttons.

“It’s not only Chinese brands; these trackers are being sold in the U.S. and Europe as well,” he says. “I would say it’s not a problem of the security of one particular vendor, but a problem of the supply chain.”

That poses a problem for the hotel industry, Hron believes, because establishments not bound by union or legislative requirements may buy inferior devices without vetting them properly, merely to satisfy new regulations. “Each hotel is buying these devices themselves—it’s not like some central authority is giving these devices to hotels,” he says. “My guess is [some are] going to buy a cheap device, and in this case, it’s pretty reasonable to think that there aren’t any analysts doing security checks on them.”

Patchwork legislation, inconsistent policies

In the coming months, hundreds of thousands of hotel workers across North America will be equipped with location-enabled panic button devices, which they will be required to have on them at all times. It’s a clear victory for hotel workers and the unions that represent them, but the introduction of a new technology may also introduce risks to individual privacy and security, especially for the vast majority of hotel workers who are not employed by a major brand or benefit from union protections.

Employees of major hotel brands and those who have the benefit of union protection are less likely to be provided vulnerable devices, but only 7% of accommodation workers are represented by unions, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Furthermore, more than a third of all hotels in America are independently run, and roughly 60% are small businesses.

“Where there’s a big unknown would be the franchisees and the smaller boutique hotels that aren’t part of a big corporate chain,” explains Brian L. Kinne, the vice president of PinPoint, a business unit of RF Technologies and maker of the HelpAlert personal safety device.

For example, hotels in Washington state are required to provide staffers with a device that can be used to emit an audible sound if they are in distress. “We saw hotels in the State of Washington and the city of Seattle over the years issue whistles, because it met the intent of the legislation,” he says.”From a logical perspective, if you hear a whistle, first of all, if you’re in the room, who’s going to hear it? And as a frequent traveler if I hear a whistle, I’m going to assume it’s some kids playing.”

Vanessa Ogle, EnseoThese stories of security failures are tragic for the health and safety of the workers we’re trying to protect.”

Kinne says that HelpAlert and other reputable vendors don’t provide customers with the capability to access the location of staffer unless they signify that they’re in distress, but cautions that not all of his competitors are doing the same. He explains that the technology isn’t capable of real-time tracking because it runs on WiFi and Bluetooth Low Energy, or BLE, and only transmits a signal when activated. Other devices that utilize GPS or WiFi connectivity, however, have the ability to transmit real-time location data on an ongoing basis.

The AHLA has released a buyer’s guide to help its members select the right technology vendor. It advises hoteliers to ask suppliers if their solution can track an employee when the device is not activated “because some local regulations or union Collective Bargaining Agreements (CBAs) may forbid tracking hotel staff during normal day-to-day operations when a staff alert device has not been activated.” In areas where no such regulations or CBAs exist, however, there is nothing preventing employers from using the devices to keep tabs on employees.

Shaky foundation

The very existence of less secure devices and vague regulations in certain jurisdictions, however, could threaten the confidence of the 1.2 million or more frontline staff who will soon be required to have the device on their person at all times.

“That is not only a real concern—we are seeing that happen today, where some of the independent hotels or smaller brands are being presented with a lower-cost solution,” explains Vanessa Ogle, the CEO of Enseo, makers of the MadeSafe employee safety system. “When this happens, not only are we putting individual teams at risk, but we’re really challenging the confidence levels of the employees, the unions, and the investor-owners, and that slows down the adoption of good products.”

It’s a difficult prospect for reputable providers who are still fighting for credibility. That’s because devices of all shapes and sizes are attempting to corner the same market, and their products come at a wide range of price points with varying levels of built-in security and privacy.

Ensuring the successful rollout of employee safety devices requires a lot of education, not just among those making buying decisions but among the staffers who will use them as well. “The technology has to work every time, but the product only works if the right policies, procedures, and personnel are put in place that allow the system to function as a system,” says Ogle. “With hotel staff, it’s particularly challenging because you have a high rate of turnover, so you need that training to make sure every person understands how you wear the device, how you hold the device, what areas of the building are covered, what the reasons to push the button are, and who will be coming when they do.”

Now or never

It’s important to get this right, says Ogle, because it’s not just about the safety of hospitality workers. Companies like Enseo and RF Technologies are branching out into other markets such as schools, hospitals, and other industries that have a need for location-based distress response services, but their products don’t just help staff members. Having a distress signal that can transmit location data to first responders also makes the environment safer for students, patients, and hotel guests.

“While the initial reason for the solution was to address sexual assault, there are other things that happen to housekeepers in hotel rooms as well,” says Ogle. “We’ve had team members that have had medical issues themselves, or found guests in rooms with medical conditions that were asking for assistance.”

Providing precise location data to first responders in the event of an emergency actually has the potential to save lives, but the technology will only be adopted if users believe it is being used appropriately. According to Ten Eyck of UNITE HERE, it is vital that policies are in place to protect workers, or these potentially life-saving devices might not get the widespread adoption the organization has spent a decade fighting for.

“The industry needs to do everything they can to make sure these devices are on, they’re working, and workers feel good about putting them on,” she says. “If not, it’s going to be all for show, all for publicity, all for the industry to say they’ve put these devices out there, but if they’re not implemented correctly, they won’t actually protect workers.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.