What did Facebook expect? The company has doubled down on its policy of allowing political ads that contain lies, explaining that it shouldn’t be in the business of evaluating ads. One unfortunate (and predictable) consequence of that is that the Trump campaign, the biggest overall buyer of Facebook ads, would take advantage. In fact Facebook’s policy looks almost tailor-fit to Trump’s Facebook ad game.

When you look through President Trump’s voluminous collection of ads in the Facebook Ad Library, you see all kinds of oddities, from contests with the prize of seeing Trump’s Superbowl ad early to sales of Trump hats that say “Woke” on the front. And hidden among the thousands of ads you occasionally find ad copy and video containing lies and half-truths. But in the last few days, as the president’s impeachment trial hit full stride in the Senate and on national TV, the campaign seems to have bumped up the misinformation level a few notches. Here are a few examples.

This one, found by Popular Information’s Judd Legum and posted on Twitter, makes the false claim that “dirty cops” illegally spied on Trump’s campaign in 2016. The president has long defended the conspiracy theory that the Obama administration wiretapped his campaign headquarters. He even ordered a government investigation, which came up with zilch. He later claimed the FBI placed a spy within his campaign. Actually, the FBI placed a confidential informant near, but not within, Trump’s 2016 campaign while investigating suspected Russian interference in the election. The FBI inspector general found no wrongdoing. Nor is there evidence that Hillary Clinton or the DNC spied on his campaign.

The ad began running on January 21, and is still running.

Now that the Trump campaign has the green light to lie in Facebook ads, here is what is happening.

Just a string of unhinged falsehoods.

In exchange for cash, Facebook is infecting its users with misinformation. pic.twitter.com/ifYs591oLc

— Judd Legum (@JuddLegum) January 23, 2020

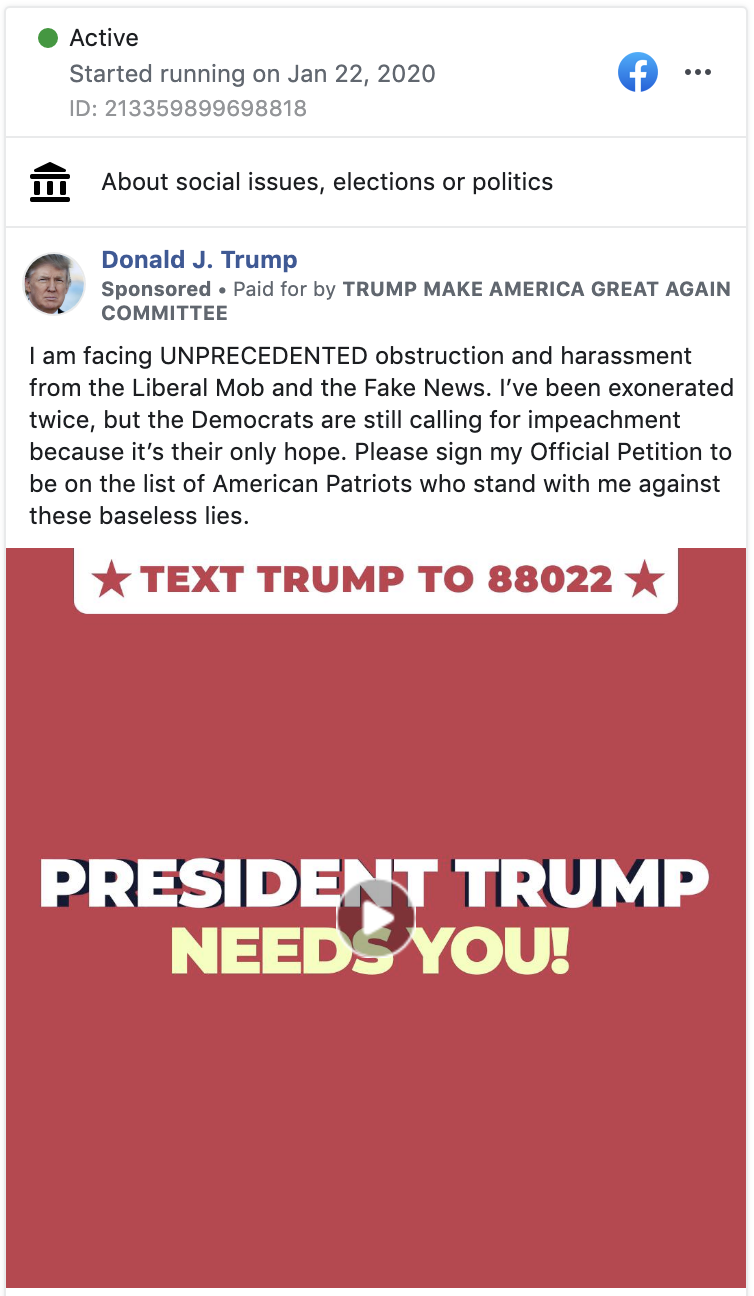

In another ad (which barely makes sense), the Trump camp claims that the president has been “exonerated twice.” One of those “exonerations” surely refers to the Mueller Report, which found ample evidence of Russian interference in the 2016 election. It also found evidence that the Trump campaign tried to conspire with the Russians but not enough to recommend charges. And it explicitly said that it could not exonerate Trump of charges of obstruction.

A number of other Trump ads show mere half-truths or milder distortions, like this ad, which is also in circulation now. The text says Trump “obliterated” Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, which is an odd way of describing the result of an election in which Trump lost the popular vote by close to 3 million votes.

The leadership and board at Facebook, whose platform was exploited by Russia to aid candidate Donald Trump in 2016, was reportedly divided on whether to allow political ads containing falsehoods. But the Wall Street Journal’s Emily Glazer, Deepa Seetharaman, and Jeff Horwitz reported in December that board member Peter Thiel, a Trump supporter and advisor, urged CEO Mark Zuckerberg and the board to ignore public concerns and adopt the company’s current political ads policy.

In a speech at Georgetown last fall, Zuckerberg said that Facebook doesn’t fact-check political ads because it doesn’t want to be an arbiter of truth and believes that people are entitled to hear what public figures are saying. Whatever the motivation, the policy allows politicians to spread as much BS on the world’s biggest social network as they wish—as the president’s campaign keeps on proving.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.