At his day job, Renzo Verbeck runs a long-standing Colorado architecture firm. For the past two decades he has designed houses, condominiums, offices, and mixed-use retail. But for the Burning Man festival this summer, he’s an architect of another sort. Alongside artist and radiology technician Sylvia Adrienne Lisse, he’s designing and overseeing the construction of one of the festival’s main attractions, its temple.

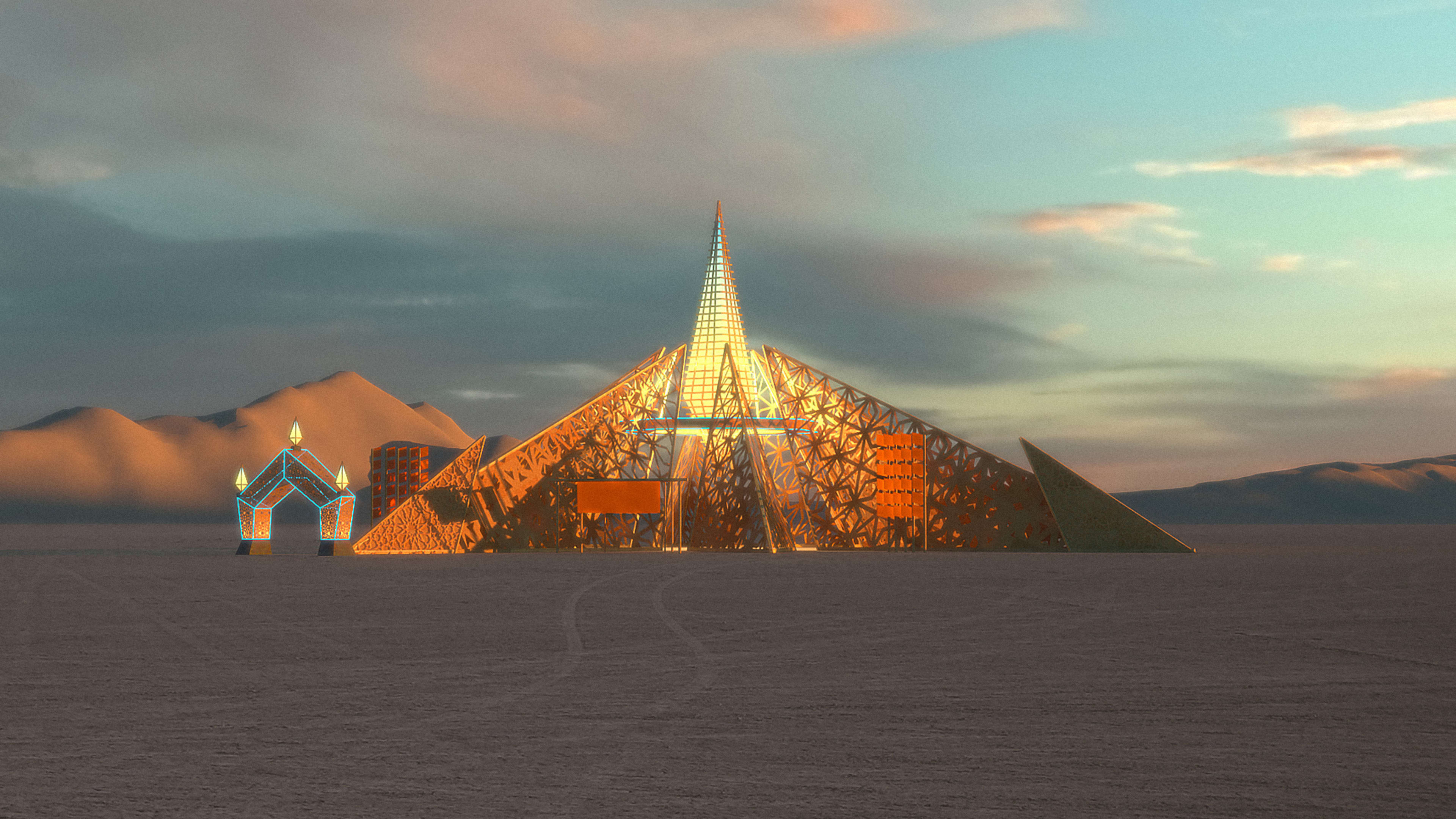

This year, the temple (which is a different design every year) will be an eight-pointed star dubbed Empyrean. That’s Greek for “of fire” symbolizing the spiritual line between heaven and earth. It’s a secular, communal space that goes up in a blaze on the last night of Burning Man, alongside the burning man himself.

Burning Man has a “leave no trace” philosophy, which means that all human materials are supposed to leave the playa by the end of the festival. This makes construction difficult, and indeed, in past years, local cities have complained that, while the desert is left clean, its garbage just gets dumped elsewhere. Verbeck has designed his temple out of wood and very minimal amounts of metal to make its cleanup simple.

“It is a little unnerving, honestly. I build buildings that are supposed to last lifetimes,” says Verbeck. “I really had to reconsider, how do you build a building that’s 220 feet across and seven stories tall, which is designed to last only a week and then [be] burned . . . It takes a while to even think about how that works as an architect. I want to build things that last and, of course, don’t burn!” he says.

Verbeck is not your typical, lifelong Burner. He first attended Burning Man in 2000 and then, while building his practice, “wanted to go back every day since,” he says. But he didn’t return until 2019 when he volunteered to spend three weeks on the crew building the temple before the event. And that’s when he began to think that he’d like to someday design the temple himself.

To be the temple designer is actually fairly competitive, he tells me. For Burning Man 2020, 20 different groups submitted plans for the temple. Alongside these plans, they had to detail how they would go about building it, from the volunteers they would sign as crew to how they would handle the logistics of feeding 100 people for three weeks in the desert as it’s assembled. “It’s a difficult place to build,” says Verbeck. “There’s no hardware store around the corner.”

The other big question that Burning Man asks is how the architect will pay for it all. Burning Man provides a $100,000 stipend for the structure, which as anyone who has built a backyard shed can attest, doesn’t go very far. Verbeck has budgeted the total cost closer to $320,000, and he has enlisted seven volunteers to help make up the rest—while launching a Kickstarter campaign for anyone who wants to chip in.

Verback has finished designing the temple and is currently planning for prefabrication that will begin in March. The temple will be constructed in the humblest of materials: untreated planks of wood, like two-by-fours and two-by-eights. These boards are flammable by design, and they assemble together easily enough that volunteers with no carpentry skills can handle much of the prefabrication in a warehouse in Oakland. Then, in the beginning of August, three weeks before the event takes place, a small construction crew accompanied by dozens of volunteers will drive heavy machinery to the Black Rock Desert in Nevada to construct it.

During the final burn, the structure will be surrounded by a safety team, with a buffer of several hundred yards between it and crowds to avoid accidents, or even suicides. While I’ve never been to Burning Man and cannot speak to the existential sensation of watching the central hub of a small city smolder to the ground in just 45 minutes, I’m in awe of the sheer amount of money and effort that goes into the project. It’s a case study of design within extreme constraints.

“It is quirky,” Verbeck agrees. “A building this size—a civic building—might take years of planning and construction, and millions or tens of millions of dollars. This will be built on site in three weeks, with 100% volunteer labor, and burned.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.