Anyone over a certain age has seen how electronic medical records (EMRs) have changed the doctor-patient experience. Today, doctors spend more time mousing and clicking across their screen than they do examining their patients. And what’s on the screen can influence a doctor’s behavior and affect a patient’s course of treatment—more than you’d think.

In the latest issue of JAMA, a research team at UC San Francisco has demonstrated how changing EMRs might impact the opioid epidemic: By reducing the default number of pain pills suggested for a prescription on screen (such as 12 instead of 15), the user interface of medical records can coax doctors to prescribe fewer pills. In fact, researchers found that in some ranges, for every one extra pill the default settings suggested, doctors prescribed 0.2 more on average.

“I definitely wouldn’t want to oversell this and say it will dramatically impact how doctors prescribe,” says Juan Carlos Montoy, a medical doctor and assistant professor at UCSF. “But it does nudge people a little bit, where at a population level, these small differences might add up.” Indeed, for a prescription of 10 pills, to reduce the count to nine would represent an overall reduction of pills in circulation by 10%.

For the first time in a century, global life expectancy has been falling, largely because of drug overdoses and suicides linked directly to opioid addiction. Opioids have been notoriously overprescribed in part because drug companies have lobbied the healthcare industry very effectively.

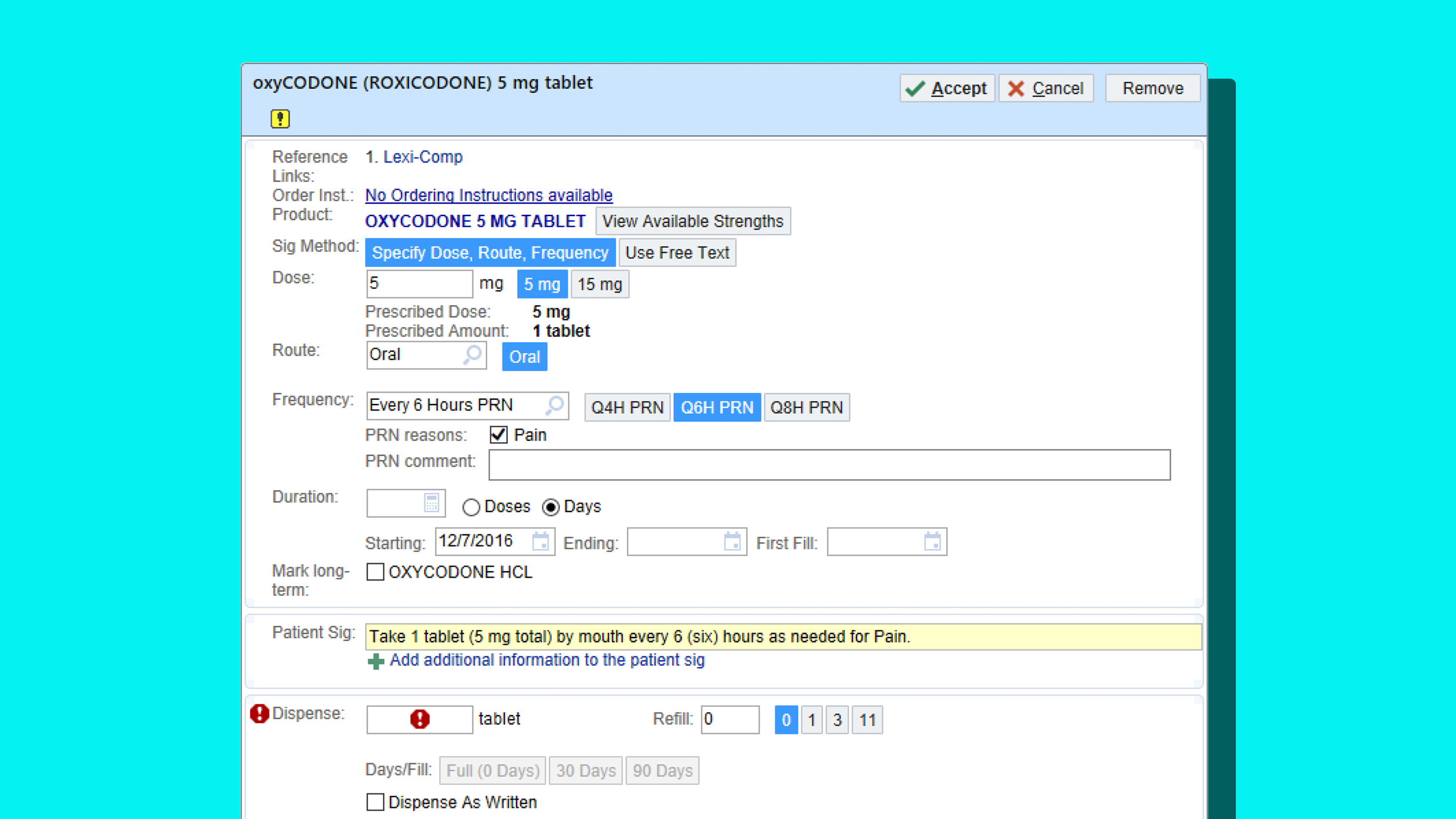

Montoy and his team didn’t attempt to answer why opioids were being overprescribed, but they did try to nudge doctors to prescribe fewer—with success. They did so by taking control of the EMRs at UCSF’s emergency department and Highland Hospital in Oakland. The researchers randomly assigned new defaults to the opioid prescriptions written by over 100 doctors and healthcare professionals in the department—without telling the doctors an experiment was taking place. Over 20 weeks, the researchers tested new pill defaults for opioids like Percocet and Oxycodone. Whereas former defaults had been 12- and 20-pill prescriptions, the researchers tested 5-, 10-, and 15-pill alternatives.

In most cases, reducing pill defaults did reduce pill prescriptions, even by small margins. In many cases the final prescriptions went unchanged; doctors didn’t seem to be swayed by defaults at all. One important finding was that at the lowest end, the default of five, doctors actually prescribed more pills than they would have otherwise—as if the doctors read the number and thought, “Oh, that’s way too low!” then signed an overly generous prescription to make up for it. “[Defaulting to] less is probably better than more,” concludes Montoy about the pill counts. “But if you put it too low, you’ll have an unintended consequences and people might overcompensate.”

One thing the team did not measure was patients’ pain, and how the prescriptions impacted the overall well-being of people. But before embarking on the research, researchers had already concluded that the testing would be of little, if any, risk to patients, while the possibility of reducing cases of addiction to opioids could be a major gain.

Montoy likens the work of his team to that of behavioral economists, who research how numbers might be presented differently to get people to invest more money into their 401Ks for retirement. Meanwhile, companies like Amazon are notorious for using behavioral economics to change the default price of items millions of times a day, to ends that likely influence user behavior and increase its bottom line.

In the context of the healthcare system, Montoy is hopeful that such research can improve the well-being of patients. While more studies are needed to understand the perfect opioid default prescription—and in truth, that figure is probably a moving target that should take into account illness and patient history in ways this study did not—Montoy points out that every hospital department already has a few assigned people who program and oversee information like the prescription defaults in their EMRs. So updating the defaults with best practices isn’t a large ask; it’s simply good medicine. “This is something that happens on an ongoing basis anyway,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.