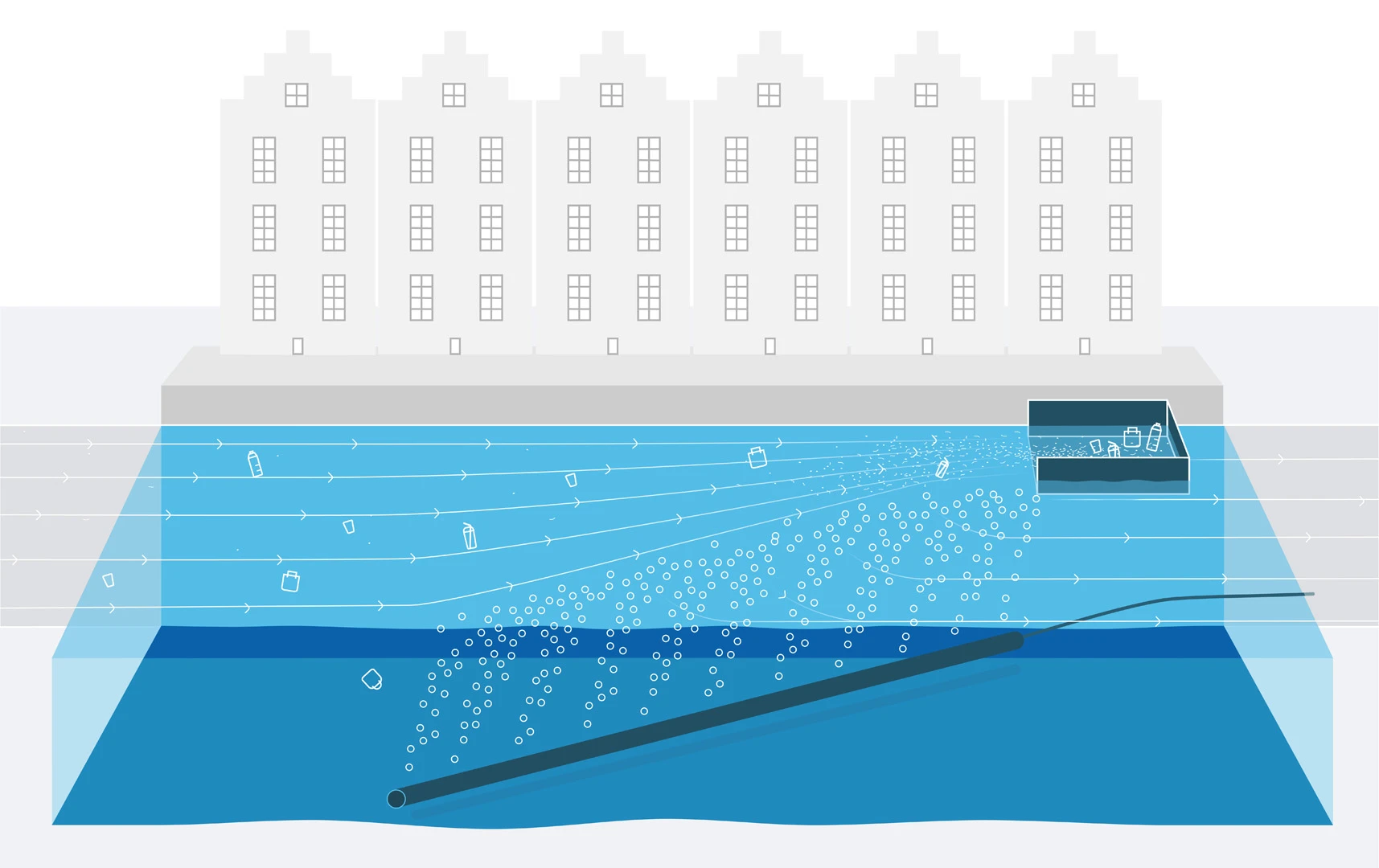

If you walk along the Westerdok canal in Amsterdam, you might not notice a line of bubbles moving across the surface. But underwater, a tube stretches along the bottom of the canal, pushing air upward. It’s a pilot test of new technology, called the Great Bubble Barrier, designed to help catch plastic waste before it flows into the North Sea.

“It can stop plastics that are drifting not only on the surface, but also underwater,” says Philip Ehrhorn, the coinventor of the device, who works on technical development at the startup that created it, also called the Great Bubble Barrier. An air compressor—connected to renewable energy from Amsterdam’s local grid—pumps air into the tube, and holes in the tube let the air escape as bubbles. Because the tube sits diagonally across the canal, the flow of bubbles combines with the natural flow of the water to help push plastic to the side, where it lands in a catchment system and can be collected by the city. In a previous test in a Dutch river, the system was able to capture 86% of the plastic flowing through the water.

Amsterdam already has a set of garbage boats that travel through canals collecting all types of trash that end up in the water. Waternet, the organization that manages water for the city, collects around 90,000 pounds of plastic waste each year. But the system tends to miss small pieces of plastic and plastic that has drifted below the water surface. The screen of bubbles can catch more. Unlike a physical barrier, it also doesn’t interfere with boat traffic or block wildlife in the water. “A lot of times these waterways are used for ship traffic, but they also play an ecological role,” Ehrhorn says. “So we shouldn’t be blocking a river—a river is a live ecosystem.”

[Image: courtesy The Great Bubble Barrier]

Ehrhorn, originally from Berlin, first started thinking about the technology when he happened to visit a wastewater treatment plant as a student in Australia. At the plant, a section of water was swirling like a Jacuzzi, and plastic waste was accumulating at the side. “That was for me the first spark to say, if I see this here, what if I do this in a way that is a lot more directed?” he says. Simultaneously, three women in Amsterdam were beginning to consider the same idea, and they won a competition to begin working on it; Ehrhorn discovered them online, and they all decided to work together. In November 2019, the city began piloting the startup’s device in a test that will last for three years; if all goes well, it will be installed in other canals.

[Image: courtesy The Great Bubble Barrier]

The company is interested in working in other cities where plastic waste currently escapes to the ocean through rivers and canals, though it doesn’t want to work in areas where plastic is dumped in rivers as a matter of course. “We don’t want to be the replacement for waste infrastructure,” Ehrhorn says. Instead, the device is meant to help supplement existing systems. And even in Amsterdam, where the city is working to increase recycling rates and reduce single-use plastic (at events, for example, organizers are now required to use reusable cups), a large amount of plastic is still littered in the water.

Other organizations are testing devices to help in similar ways: The Ocean Cleanup released a robotic trash-collecting system last year that also pulls waste out of rivers. (The Ocean Cleanup, by contrast, is working in areas where recycling infrastructure is currently poor or nonexistent, noting that most ocean plastic comes from key rivers where the worst dumping occurs.) “I think the plastic problem is so complex that there’s not going to be one solution that’s going to solve everything,” says Ehrhorn. By one estimate, as much as 2.4 million metric tons of plastic flows into the ocean from rivers each year, along with millions of additional tons from other sources.

The Great Bubble Barrier is working with a nonprofit, the Plastic Soup Foundation, which is counting each piece of plastic collected and noting the brands on the packages. The data will be publicly available. “We still don’t know enough about how much plastic we actually have in our rivers or how much it’s actually ending up in the oceans from the rivers,” he says. With the data, the team also wants to help solve the problem upstream—by identifying what types of trash show up most, the city can potentially start to draft new policies to stop the problem. “Hopefully, in the future, these will not end up in the water in the first place.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.