The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect in May 2018 to give users more transparency into and control over their personal data. A key component is that companies must now ask users for their explicit consent before hoovering up their data—but new research suggests that only 11% of major sites are designing these so-called consent notices to meet the minimum requirements set by law.

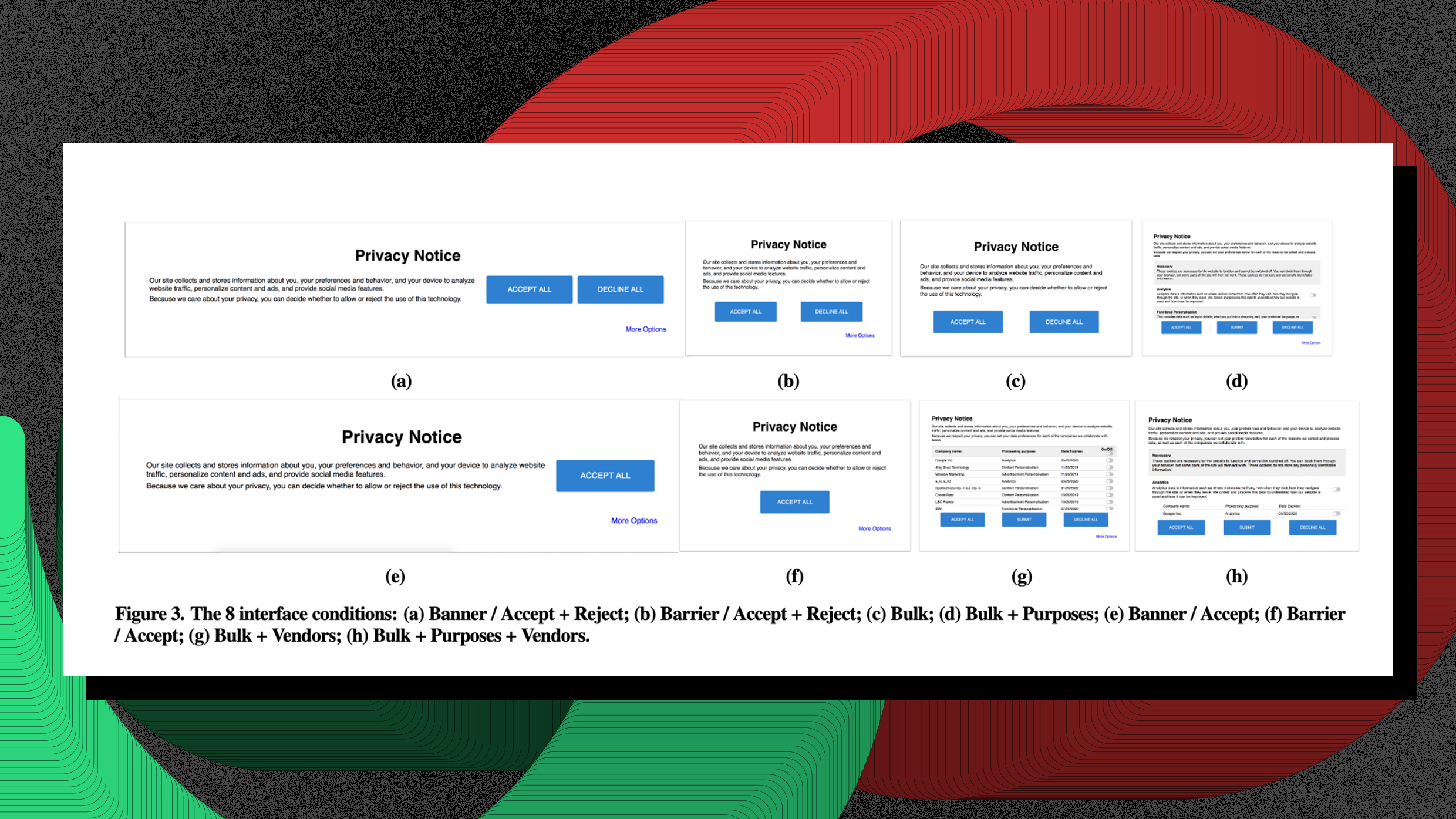

The research conducted by Aarhus University, University College London, and MIT took place in two parts: The first reviewed the compliance of the top 10,000 websites in the U.K., finding that only 11.8% of those sites met the minimum requirements set by law. The second looked at the effect of interface design on data consent actions and found that the style of the consent notice could increase or decrease acceptance rates by about 20 percentage points. So there are obvious solutions. But companies are deliberately opting not to use them.

According to the study, websites often outsource the design of these pages to what is commonly called consent management platforms (CMPs) or third-party code libraries that claim to help website owners meet compliance regulations. But as that 11.8% compliance stat shows, CMPs just aren’t cutting it. A big reason why is that their design puts companies in violation.

The GDPR defines consent as “any freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.” In layman’s terms, that means the user has to explicitly agree to share their data.

Passive agreement won’t cut it, so that puts implicit or opt-out consent—forms that require users to uncheck boxes, or that consider continued use of the site consent—in violation. Forms that emphasize “agree” over “disagree,” or that make the “reject” option more difficult to find, are also in violation. “Accept all” buttons are only valid if there is an additional option to consent to each specific instance of data use—and all organizations processing the data have to be specifically named. Basically, sites need to follow three core rules: They need to ask for explicit consent, they should make “accept all” as easy as “reject all,” and they should not have pre-checked boxes. If the user has to follow a trail of digital breadcrumbs just to deny consent to sharing data, that interface violates the GDPR.

So are design patterns that prevent the user from making an easy and clear privacy decision examples of simply poor design, or are these design patterns intentionally nudging users to share data? According to the study, CMP vendors are “turning a blind eye to—or worse, incentivizing—clearly illegal configurations of their systems.”

I asked David Carroll, a professor of media design at Parsons, if he thought design patterns that violate the GDPR are intentional or just incompetent. “It has to be intentional because anyone who’s actually read the GDPR in an honest way would know that it’s not right,” says Carroll. “Both the design and the functionality of them are very manipulative in favor of the first- and third-party collectors where possible.”

One way websites might engage in this type of malignant behavior is through dark patterns—which this study defines as “interface designs that try to guide end users into desired behavior through malicious interaction flows.” This includes default settings that are privacy-intrusive and that users have to opt-out of, discouraging privacy-friendly options by making them more difficult for the user to find, all-or-nothing choices, and yes, those hellishly long privacy agreements.

In the researchers’ second study, reviewing the effects of designs on user consent or rejection of consent, they found that participants limited virtually all interactions (93.1%) to the first page of the pop-up CMP shown to them. When available, participants clicked a “more options” link only 6.9% of the time. When given a scrollable list of data collection purposes, participants ignored it 68.6% of the time. “Anything not immediately visible to the user, anything requiring interaction to access,” wrote the researchers, “might as well not exist.”

When participants were shown a visualization of their consent patterns and “asked if it matched their ideal settings, the responses were predominately that it did not.” The majority of this study pool was college-educated—not unlike the general population of either the European Union or the United States.

There are few solutions. The researchers suggest that regulators use automated tools to more quickly scan for violations, that designers create tools to help regulators enforce the law, and that regulators restrict CMP vendors so that only sites in compliance with GDPR rules can go live.

Another avenue, of course, is overhaul: going beyond improving status quo enforcement and making positive changes, such as designing consent forms that are user-friendly—clearly written and allow users to quickly and easily make privacy decisions that are best for them.

The issue is that there is no incentive to do this: If a company’s UX makes consent options transparent enough to be compliant with the GDPR, their data collection will be a tiny fraction of what it was previously, Carroll tells me. That’s not in the interest of most businesses today.

Okay, so there’s no carrot. How about a stick? Bad news here, too. “The regulators are so weak and are unwilling to really do any penalties, from a business perspective there’s much to be afraid of yet,” says Carroll. For a company to get noticed by GDPR regulators, Carroll says the burden is on the user to call foul by filing a complaint or lawsuit. (Brave, the company that produces a free web browser by the same name, says it has filed such a lawsuit against Google.)

Carroll knows how difficult it can be to put a company in check. Carroll filed a complaint against London-based consultancy Cambridge Analytica in 2017, to retrieve details about how it had clandestinely mined personal data from him. According to Carroll, when Cambridge Analytica filed for bankruptcy, the company was then protected by a moratorium. So he never got his answer. The saga “exposed the escape valve of last resort” for companies in violation: bankruptcy.

According to the researchers, some designers have developed alternatives to existing consent forms. There are “nutrition-label” like notices that use icons to indicate how data is used. These were developed by Patrick Gage Kelley and others in 2009. There’s also a color-coded, expandable “interactive matrix visualization” that was developed by Robert W. Reeder and others in 2008. Yes, both of the solutions mentioned by the study were created over 10 years ago. Tellingly, few to no companies have actually started using them.

That’s because dark patterns are a symptom of business that prioritizes data as a modern kind of currency: Why give it away if you don’t have to? “It’s a design problem,” Carroll says, “but it’s a business model problem first and foremost.” The smoke and mirrors distract from the main cause of noncompliance: Companies don’t want to change.

Such an abysmal level of GDPR compliance can only make you wonder about the influence of dark patterns and the level of data collection here in the United States. The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)—a sweeping regulation that advocates for consumer privacy protections, and the closest to the GDPR here in the U.S.—technically went into effect on January 1, 2020, although the attorney general can’t begin enforcement until six months after regulations are in place. It’s expected that other states will follow suit and adopt similar privacy laws, but the when and the how of that legislation will have to be determined on a state-by-state basis. The Verge suggested that California—the first state out of the gate—isn’t in a position to enforce the new legislation anyway, because parts of the regulation were “still unclear” and enforcement regulations weren’t finalized by the time the law went into effect. And while the CCPA is a great first step, it’s not as extensive as the GDPR. Under the new California law, companies can still collect your data. The difference is that users now have the ability to opt-out and companies are obligated to tell users what personal data they collect or to delete that data if a user requests it. But again, there’s little incentive for companies to make these features easy to use.

I wondered if considering the lax regulation of the GDPR, there would be any incentive for states in the U.S. to be more aggressive. Offering us a small piece of silver lining, Carroll thinks there is. Because the ballot initiative was so popular, the California attorney general “may have a political reason to show some teeth behind the law when it becomes enforceable.”

It might take just one domino to fall for dark patterns to become a thing of the past. “Even if one company was singled out, it would ripple through the industry and a lot of UX designers would say, ‘We have to redo our consent box,'” Carroll hypothesizes. “It could happen in the coming year, but until it happens, I think we’ll see more of what we have here.” Consider this a warning: Companies are still figuring out how to siphon off your data, and they’re using tricky design to do it. Chew on that next time you mindlessly click “agree” on a consent form.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.