Australia’s wildfires—which, since September, have burned 17.9 million acres of the continent—have not only turned skies vermillion and made breathing the air a health hazard, they have also claimed the lives of an estimated 27 people and 1 billion animals. This global warming-fueled crisis began thanks to a combination of lightning, arson, and an unusually hot and dry summer season.

Historically, Australia’s indigenous Aboriginal community has practiced cultural burning on native land to control weeds and increase biodiversity. In indigenous communities, this ritual (also known as fire-stick farming) has long been known to be a preventative measure against massive wildfires like Australia’s current one. But because it’s a form of traditional ecological knowledge and not taught in institutions or practiced by Australia’s government, cultural burning as a land management strategy has been ignored for centuries.

In Lo-TEK, Watson explores the living root bridges of Mawlynnong village, India, the Mahagiri rice terraces of Bali, Indonesia, and the floating city of Ganvie in Benin, along with other examples of indigenous design practices in places like Peru, the Philippines, Tanzania, and Kenya. She ends up with a text that chronicles the ways indigenous wisdom can be used to supplement high-tech design.

As a native Australian, the relevance this text has to the fires burning in her homeland today is not lost on Watson. Growing up in Australia’s colonial culture, it was easy to think of nature as pristine—not a living, breathing part of society, ripe with materials for designing and building technologically advanced structures. When she started to notice that the Aboriginal community understood its relationship to Australia’s landscape differently than the mainstream majority, and observed the “Aboriginal relationship to land and country and how that manifests in architecture,” she began thinking about how far we’ve veered from the tools nature provides us, all in the name of modernity.

For instance, deliberately setting fires to small areas of forest and brush is tradition among Aboriginal communities in Australia. “Pyrotechnology, fire farming, and cultural burning is a custom that you see all over the world, a slow burn in a ground system that’s really well controlled,” Watson says. “There are stories about properties that have had cultural burning and the fires now are going around those areas and not even touching them.” Cultural burns are cooler, slower moving, and closer to the ground than wildfires, and allow for animals to have the time and treetops available to seek refuge from the flames. The way these small fires are lit—with matches and in a circular pattern—comes from thousands of years of shared knowledge.

“It’s more than just putting the fire on the ground—it’s actually knowing the country, knowing what’s there . . . the soil types, the geology, the trees, the animals, the breeding times of animals, the flowering times of plants,” Dennis Barber, Aboriginal cultural fire practitioner, told the Sydney Morning Herald.

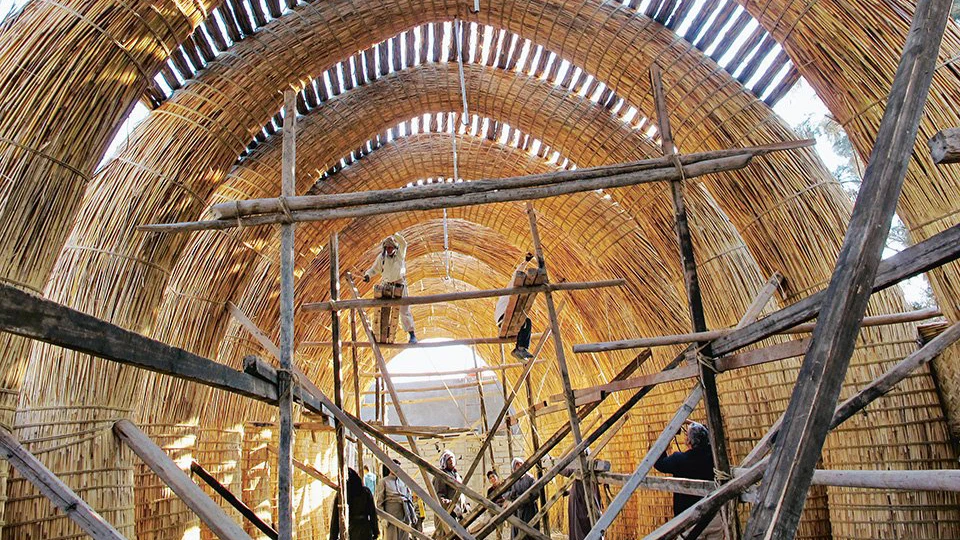

In highlighting these indigenous practices, Watson sheds light on the failures of contemporary land development and architectural production. “There’s a parable about technology; [we need to] question what we think and how we got here, and think about [design] differently. We need to reframe [it]. Then there’s this tool kit of methods and practices . . . that we can apply in urbanized conditions,” she says. Green roofs are now a popular, sustainable alternative to traditional tile ones, but come from a long line of natural shelters (like the Ma’dan homes built entirely from qasab reed in Southwest Iraq). The larger architectural community only started to consider green roofs sophisticated when they started being produced mechanically, instead of by hand using found materials.

“We need to think about different [futures] . . . we need to surrender to the idea that we know our cities are going to be filled with water and figure out how to work with that,” Watson says. “How do we not just fall back to using high-tech solutions and use nature technology instead? It can be a hybridized high-tech/low-tech solution . . . we’re not thinking about this technology as potentially a starting point for new technologies, we’re trying to solve problems with the same tool kit that created the problem in the first place.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.