In 2018, a series of earthquakes struck the Indonesian island of Lombok, killing 560 people. The area was reduced to rubble and hundreds of thousands were displaced. Near the epicenter, most buildings were destroyed, in part because of poor concrete construction. A new project in the area aims to help villages rebuild with earthquake-resistant houses made of local bamboo.

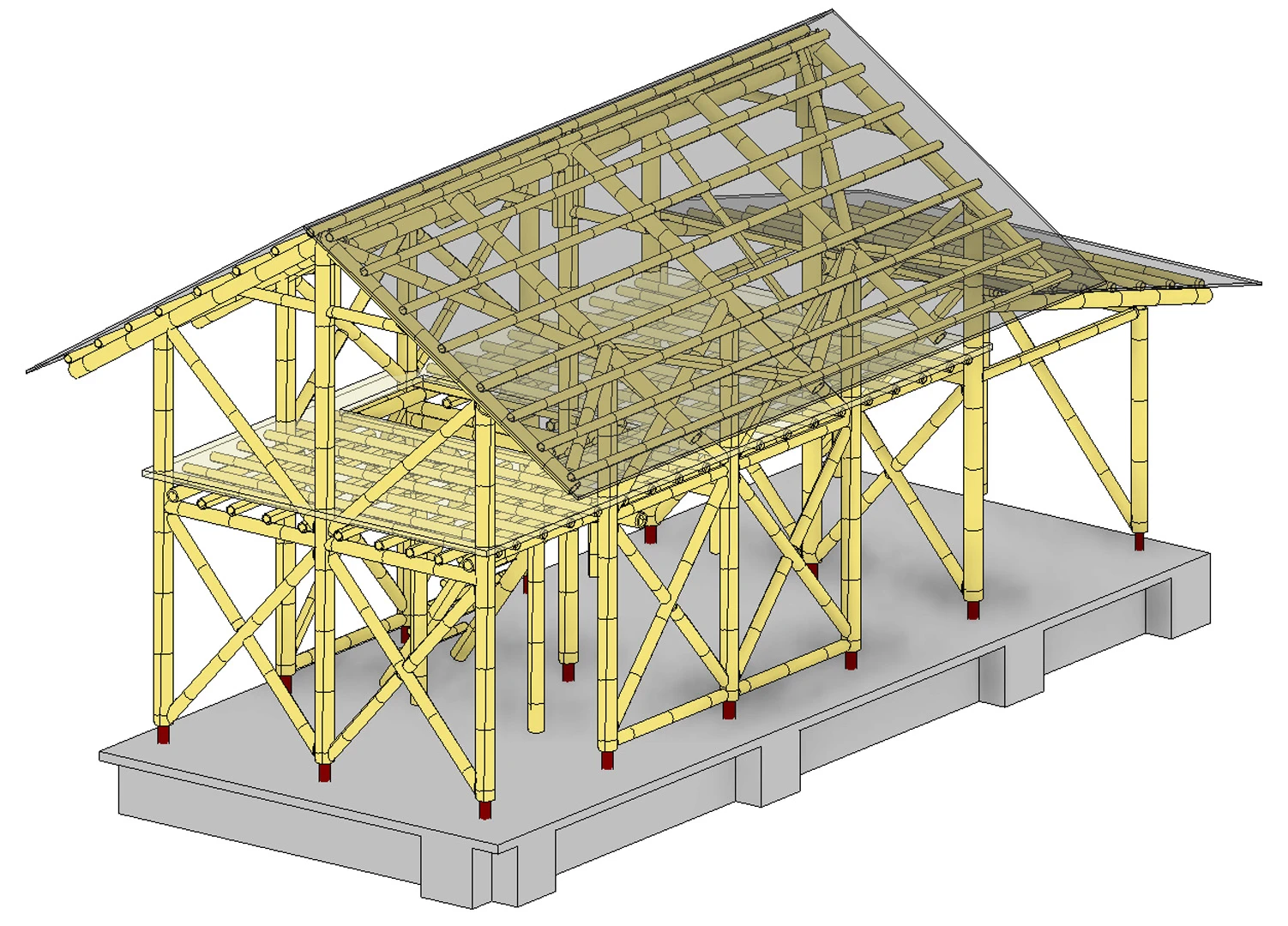

“Bamboo is a lightweight material, and it’s very strong,” says Marcin Dawydzik, a structural engineer at the London office of Ramboll, the engineering, design, and consulting company that designed a template for the house. The light weight means that when an earthquake hits, there’s less mass to creates stresses on the structure. The material is also flexible. “As the earthquake happens, the house will move a little bit and wobble and shake,” he says. “But that actually means that the energy is being dissipated, and all that movement makes it survive very strong earthquakes.”

When the earthquakes hit Lombok, Dawydzik happened to have a friend living in the area working with a local nonprofit. He reached out to check on her and learned that her house—made from bamboo—had survived, while neighboring concrete houses had been obliterated or were no longer liveable. “I thought, I’m an engineer, working for an engineering company,” he says. “I have the skills. How can we help?” He ended up traveling to Indonesia a few months later to see the destruction and to begin to work on a bamboo design that could be validated as structurally sound and used more broadly.

Using the bamboo itself was a hurdle, even though it grows abundantly in Indonesia and traditionally was used for construction. “Bamboo is viewed in Indonesia a little bit as a kind of poor man’s timber,” he says. “That’s what they call it . . . They look to the Western world and they see big concrete buildings full of glass and steel and concrete and they want to live the same way.” The problem is that the strength in concrete comes from the reinforcement inside it, and if it’s made incorrectly, and if a building is designed incorrectly, it’s likely to fail in an earthquake. (Concrete is also a contributor to climate change, which is leading to other disasters in Indonesia as the sea level rises.)

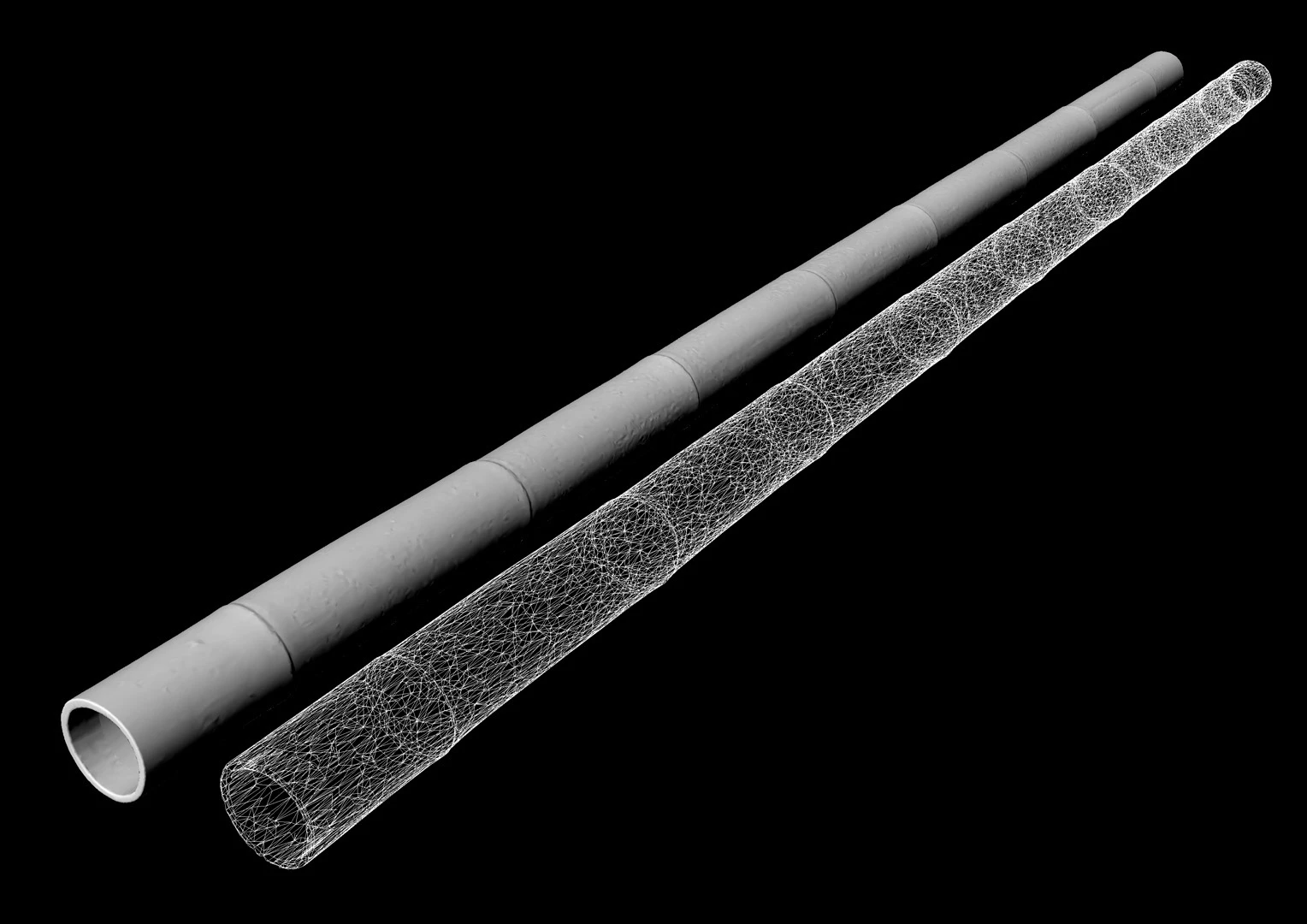

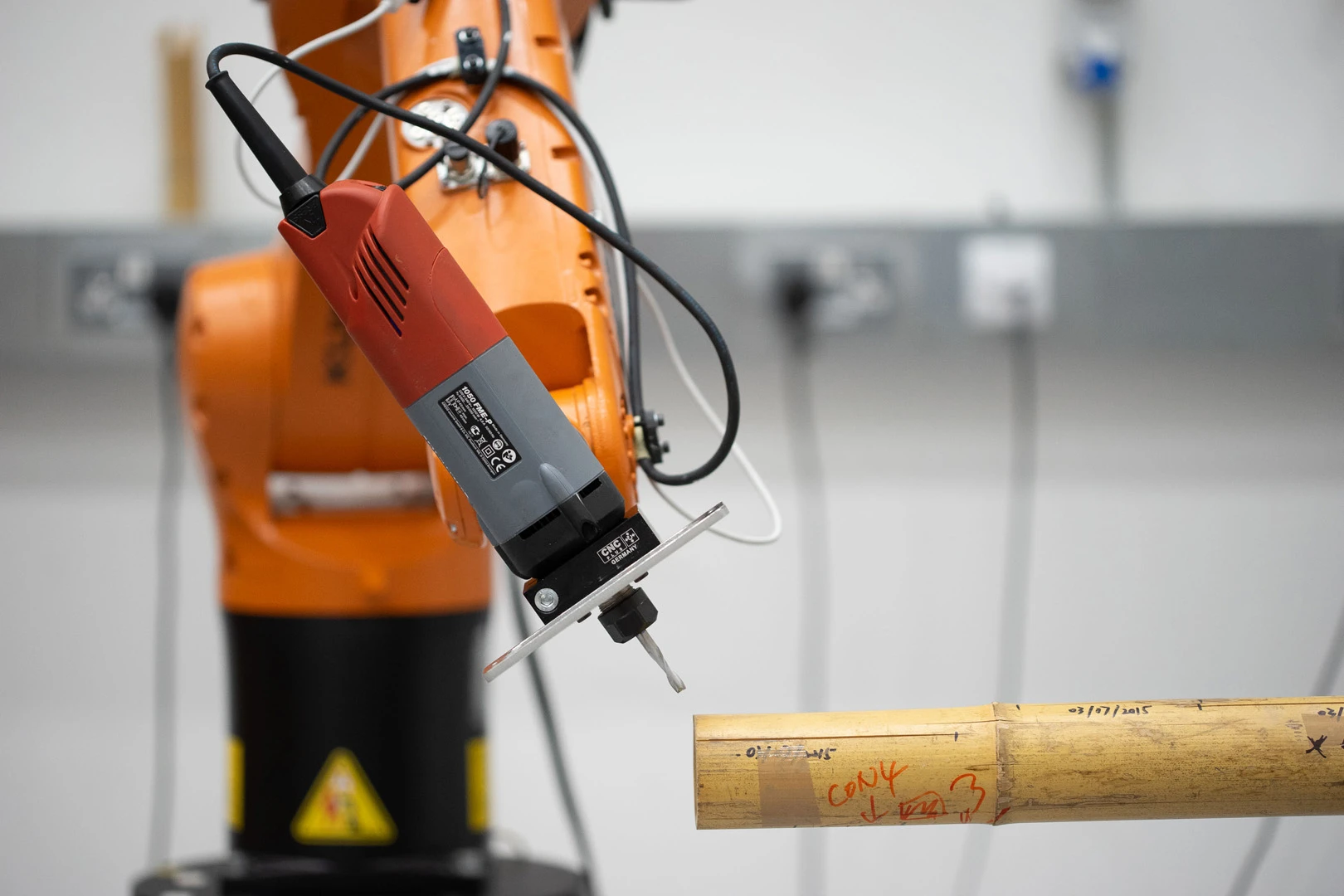

The engineering team returned to London to work on the design, and partnered with researchers at University College London who used 3D scanning on pieces of bamboo to help model the house’s performance. “What we do is to try to essentially create a digital blueprint of each pole,” says Rodolfo Lorenzo, an engineering professor at the university. Unlike a steel beam, a bamboo pole doesn’t come in a uniform size, but by scanning the material, the engineers were able to better understand how the design would perform.

Late last year, the engineers partnered with a local nonprofit, Grenzeloos Milieu, to build three template houses in three villages, working with both skilled and unskilled community members on the construction, educating them about how the structure was designed to resist earthquakes. The nonprofit is now working with local communities to plant bamboo forests that can be used to build future houses. As the young bamboo grows, the shoots can be used for food; after two or three years, the material can be harvested to make crafts and furniture. After five years, it’s large enough to be used in construction.

The team is currently tweaking the design and creating a construction manual that anyone will be able to use. “It’s a step-by-step manual like you’d use to build your own shelf from Ikea,” says Dawydzik. An online tool may also let someone enter the dimensions of their own plot of land and then output a custom design for a house. He’s hoping that it could be used anywhere bamboo is abundant. “I imagine it being a reference for other NGOs around the world.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.