At the stroke of midnight on December 31, the City of San Diego’s long experiment with facial recognition technology came to an abrupt end. For seven years, police had used a sophisticated network of as many as 1,300 mobile cameras (smartphones and tablets) and compiled a database of some 65,500 face scans—placing California’s second-largest city at the center of a national debate about surveillance, privacy concerns, and algorithmic bias.

Now, after the California legislature instituted a three-year ban on police use of mobile facial recognition technology, one of the nation’s most overhyped and least well-understood policing tools has been switched off.

Some local police are frustrated, and privacy advocates are optimistic. But it’s almost completely unclear how effective the initiative was, since the city’s law enforcement agencies didn’t track the results. And a police spokesperson told me that they were unaware of any arrests or prosecutions tied to the use of facial recognition technology.

Introduced in secrecy

Introduced in 2012 by the countywide San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) without any public hearing or notice, the Tactical Identification System (TACIDS) gave law enforcement officials access to software that focuses on unique textures and patterns in the face—ear shape, hair, skin color—using the distance between the eyes as a baseline. In less than two seconds, the software compares those unique identifiers to a mugshot database of 1.8 million images collected by the San Diego County Sheriff’s office.

The system, whose software is supplied by surveillance vendor FaceFirst, is part of a larger database called the Automated Justice Information Systems (ARJIS), a network formed by city and county agencies to provide criminal justice information services to each other.

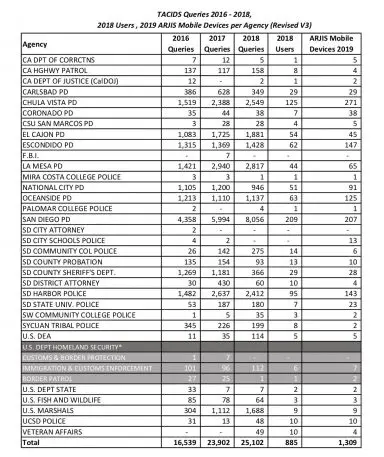

In all, 30 law enforcement agencies, including the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration & Customs Enforcement, had access to TACIDS. But it was the San Diego Police Department that used the system the most, which the department says reflects the size of its police force (over 1,900 officers). According to SDPD, the department used facial recognition scans more than 8,000 times in 2018, almost double the number in 2016, which it says was largely due to the formation of a new division, Neighborhood Policing Division (formed in March of 2018), aimed at addressing the issue of homelessness. SDPD equipped officers in the new division with TACIDS devices to help identify homeless people, who often do not have identification.

San Diego’s love affair with surveillance technology extends beyond just TACIDS. According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for digital privacy, the city has the highest concentration of surveillance technologies of any of the 23 counties that comprise the northern side of the U.S.-Mexico border. The San Diego County Sheriff’s Department also uses tattoo matching software from a national vendor, DataWorks Plus. And a license plate reader system supplied by Vigilant Solutions has often been coupled with TACIDS, although in May of this year, San Diego quietly ceased sharing license plate data with federal agencies, including Border Patrol and other Department of Homeland Security agencies. And for several years the San Diego County Sheriff’s Office, as well as some smaller police departments in the county, have been operating drones to photograph crime scenes, locate homeless encampments, and assist with emergency response.

Statewide, concerns about the expanded use of facial recognition technology in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and other cities led to pressure on lawmakers to pass the ban. Back in the fall, the American Civil Liberties Union found that when it ran photos of California state legislators through Amazon’s Rekognition software, the program mistakenly matched 20% of them (more than half of whom were lawmakers of color) to mugshots in a massive state law enforcement database.

Community leaders, such as San Diego Councilmember Monica Montgomery, have raised concerns about the accuracy of the matches made by TACIDS and say that it violates the civil liberties of residents. The lawmaker, who represents the city’s Fourth Council District and is the chair of the city’s Committee on Public Safety & Livable Neighborhoods, has “stood with advocates in voicing concerns over surveillance capabilities and how these capabilities are utilized,” according to a spokesperson.

Now, the department is prepared for a return to traditional policing. “We will be terminating the usage of the [TACIDS-enabled] devices,” says a SDPD spokesperson, noting that since the department is only the end user of the program, no department face data is stored in the devices. “The only biometric technology we will be utilizing is fingerprint scanners.”

“When I showed him his booking photo, his jaw dropped”

Over the last seven years, the program has been used in a variety of ways, both controversial and laudable. TACIDS has enabled officers to connect homeless people with service providers and identify drug overdose victims so that the victim’s families could be alerted. But it’s also been criticized for its use in cases where people were photographed without their consent—including an African American man driving by his grandmother’s house and a retired firefighter who had a dispute with a man he claimed was a prowler—to determine whether they had criminal records. (They didn’t.)

Law enforcement officials who work with Immigration and Customs Enforcement have been particularly positive about their experience using TACIDS. An ICE agent told the Center for Investigative Reporting about using the device during a warrant sweep in Oceanside. When he ran a man’s photo through the system, he found out that the suspect was in the country illegally and had a 2003 DUI conviction in San Diego.

“I whipped out the Droid (smartphone) and snapped a quick photo and submitted for search,” the immigration agent wrote in his testimonial for the Automated Regional Justice Information System. “The subject looked inquisitively at me not knowing the truth was only 8 seconds away. I received a match of 99.96 percent. This revealed several prior arrests and convictions and provided me an FBI #. When I showed him his booking photo, his jaw dropped.”

Just last month, ICE lost its access to the shared database, and its accounts were disabled since it refused to sign and comply with updated California Department of Justice guidelines, according to SANDAG. A rep for ICE did not return several requests for comment.

Police unaware of any successes in arrests

Police officers are mixed on the potential impact of the new moratorium. “While facial recognition could be a useful tool, we do not foresee the three-year moratorium on mobile face recognition use by law enforcement as having much of an impact on our department,” says Lieutenant Justin White, media relations director for the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department.

But Jack Schaeffer, the president of the San Diego Police Officers Association, says he has some concerns over A.B. 1215’s ban. Instead of a moratorium, Schaeffer believes clearly defined face recognition usage rules would be preferable.

Shaun Rundle, California Peace Officers Association“You can’t perfect it if you can’t even use it.”

“We should put restrictions on technology with a clear set of rules,” says Schaeffer. “There are a lot of situations where facial recognition could help let us know who our suspects might be in a series of crimes, or inform us about a threat of violence . . . So, I really am reluctant about a moratorium.”

In August, Shaun Rundle of the California Peace Officers Association said that keeping citizens safe involved using the most cutting-edge technology. At the time, he had hoped California wouldn’t outlaw face recognition, saying, “You can’t perfect it if you can’t even use it.”

“We hope to get to that place where there’s no misidentifications,” Rundle added, responding to the finding of the ACLU test that matched legislator’s faces to mugshots. “But to say we can’t even use it at the get-go, that’s where we have a problem.”

Despite law enforcement concerns over the face recognition ban before the technology can be “perfected,” there are few statistics that measure its effectiveness, even after seven years of use in San Diego. Lieutenant White of the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department said they have not been tracking TACIDS successes in arrests and prosecutions, so they do not have any statistics. Neither does the SDPD, according to spokesperson Lieutenant Shawn Takeuchi.

“The stereotype of [face recognition] we see is real-time use that leads to the identification of a violent guy that is wanted worldwide, and it leads to an arrest,” says Takeuchi. “That’s absolutely not how we view and utilize these devices.”

Takeuchi says that when an officer stops an individual for a violation of either a local ordinance or state law, and they must issue that person a citation, SDPD policy requires them to first confirm the individual’s identity. In the past, if a suspect didn’t have identification and refused to identify themselves, SDPD would arrest the individual, take their fingerprints at the jail, and run the prints through state and federal databases. Takeuchi says that face recognition and mobile fingerprint scanning devices are two ways that officers can avoid having to arrest and book an individual for failing to identify themselves. Of those two technologies, Takeuchi says officers actually prefer fingerprint scanners over mobile face recognition devices, given that the searchable TACIDS database was only local, while the fingerprint database is national.

At the request of Fast Company, Takeuchi made inquiries throughout the SDPD and is unaware of any success stories in which TACIDS devices helped to successfully arrest and prosecute an individual. That said, there might have been success stories, but he just hasn’t heard of them since the department doesn’t keep statistics on face recognition usage.

Although usage of the devices will be terminated across San Diego County law enforcement agencies, it’s currently somewhat unclear what will be done with face recognition devices equipped with TACIDS technology, which was created by FaceFirst, a contractor based in Encino, California, that offers face recognition systems for a variety of markets, including retail, banking, airports, and schools. The company, which did not return several requests for comment, appears to have started marketing its face recognition technology in the late 2000s, when it began applying for grant funding.

As for the facial template data captured by TACIDS, it will be retained for three years for audit purposes with the name and ID of the law enforcement user, “the name of the agency employing the user, and the date and time of access,” says Jessica Gonzalez, the spokesperson for the Automated Regional Justice Information System (ARJIS), a network formed by city and county agencies to provide criminal justice information services to each other.

Gonzalez adds that access to the TACIDS face recognition application will be removed from all devices. Additional transparency into ARJIS’s compliance process will likely come after the January 1 shutdown.

Beyond the ban

For proponents of the ban, it’s a first step to a long-overdue realignment of priorities in the state. Matt Cagle, technology and civil liberties attorney at the ACLU of Northern California, who led the lobbying effort to pass A.B. 1215, says California acted boldly to protect civil rights and liberties from threats posed by “an unprecedented surveillance technology.” Instead of facilitating the expansion of what the ACLU sees as a “discriminatory surveillance state,” Cagle believes that California needs to invest resources into the fostering of free and healthy communities where everyone can feel safe, “regardless of what they look like, where they’re from, how they worship, or where they live.”

Matt Cagle, ACLU of Northern California“But face surveillance remains a threat to civil rights and liberties even if its use is fully known to the public.”

“We look forward to building on California’s victory and urge other legislatures to follow suit,” says Cagle. “Moratoria and bans help ensure people don’t become test subjects for an invasive and dangerous tracking technology that undermines our most fundamental civil liberties and human rights.”

California’s ACLU offices plan to ensure city, county, and state law enforcement agencies comply with the deadline to shut down face recognition programs, whether by CPRA requests or other means. Cagle says the ACLU of California and its civil rights partners will use all available tools to ensure full compliance. Regarding TACIDS, in particular, Cagle emphasizes that people should never be subjected to “flawed and dangerous surveillance” without their knowledge or consent.

“But face surveillance remains a threat to civil rights and liberties even if its use is fully known to the public,” he adds. “People are less safe and less free when they know their identities and locations will be tracked simply for walking down the street or attending a protest.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.