This is the second installment in The Design of Y2K, a series telling the stories behind the most influential products of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

In 1996, the burgeoning internet service provider American Online, also known as AOL, was growing fast. The company had just implemented a radical new pricing model: unlimited internet for just $20 per month, rather than a price-per-minute system. User numbers exploded, and AOL’s engineers were fighting to keep up with demand.

Eric Bosco joined the company a week before the unlimited plan rolled out. With the rest of the team busy building capacity, his boss assigned the young engineer a project that was still just an idea on a white board: AOL Instant Messenger. Bosco became part of a small, largely autonomous team, a kind of “skunkworks” within AOL, that was building the ambitious messaging functionality. They were led by the vision of Barry Appelman, who conceived AIM as a free, interoperable service—not just for AOL users, but all internet users.

Yet soon, AOL leadership decided to turn AIM into the core messaging service within the AOL ecosystem, setting up a tension between the team’s vision of AIM as a free messaging service versus AOL’s vision of AIM as a feature reserved for subscribers. After all, why give away something for free and cannibalize AOL’s product? “Our counter argument was: If we don’t cannibalize ourselves, somebody else surely will,” Bosco says.

It caught like wildfire.”

In those early days, the AIM team didn’t even have the servers they needed to launch the software. Instead, they intercepted a load of outgoing Hewlett-Packard servers from the AOL data center and repurposed them. “I would administer the servers at night and do the software engineering during the day because I couldn’t ask for any other AOL resources,” Bosco remembers. Likewise, when it came to the interoperability between AIM and the rest of the web, the team planned to beg for forgiveness, rather than ask for permission.

They never had to. AIM was a hit, and soon its user numbers were growing exponentially. As Bosco puts it, “It caught like wildfire.”

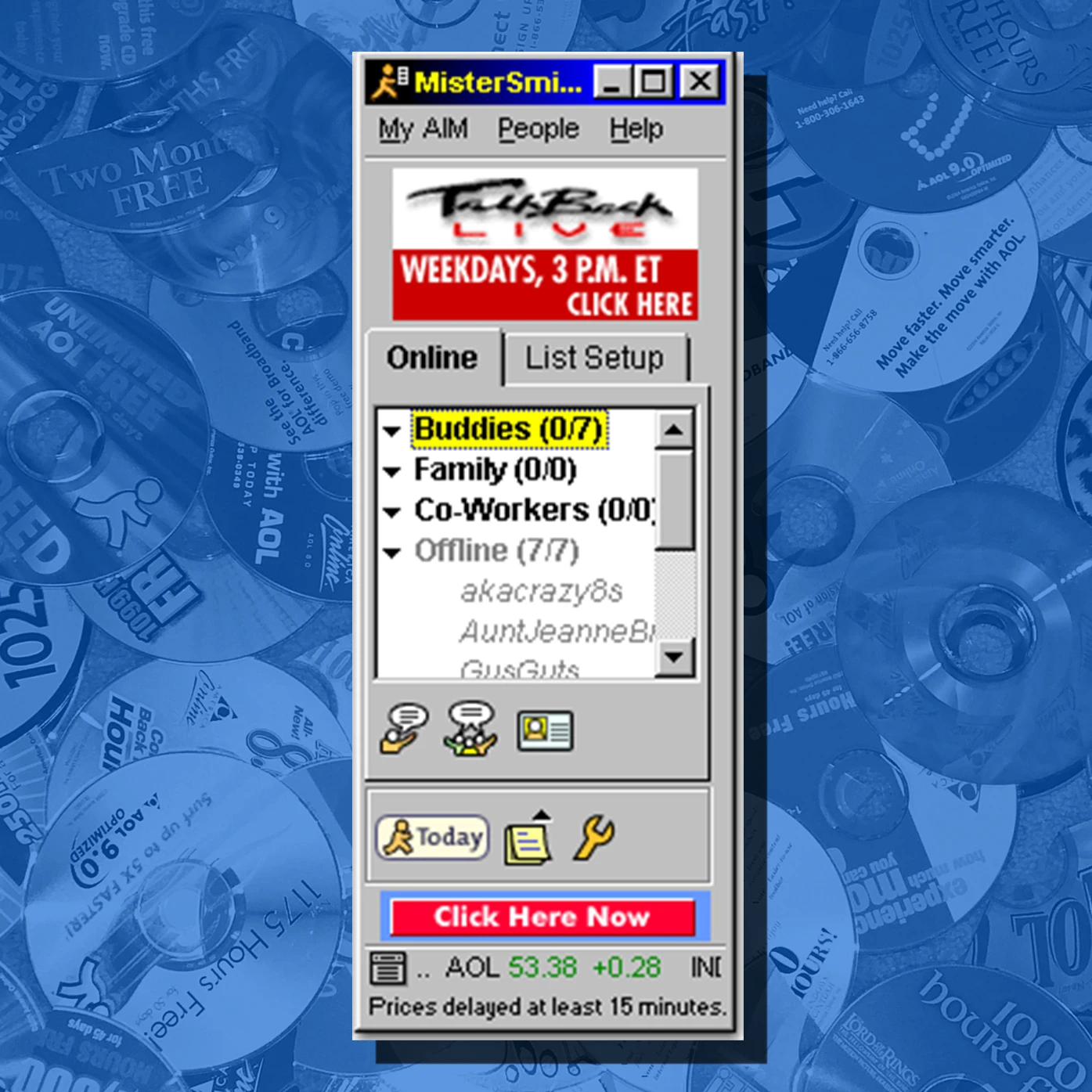

AIM lasted for almost exactly two decades, launching in 1997 and shuttering in 2017. It was the quintessential millennial technology: a free messaging service that allowed people to broadcast their personalities, via avatars and profiles, for semi-public consumption. AIM invented the idea that you were always online—and if you weren’t, you’d set up an away message to let people know. It created a UX framework that nearly every other messaging app in the world has borrowed in the two decades since. The designers and engineers who built it, many of whom were just out of school, pioneered ideas about user experience design, software engineering, and even branding that have since become industry standards.

Though its official sunsetting in 2017 inspired many nostalgic blogs about the chat service, it’s safe to say AIM’s legacy is still very much alive in the apps we use every day—and in the contours of the internet at large.

A folksier, friendlier internet

By the mid-1990s, AOL was introducing millions of people to the internet for the first time. It was a historically unique design project: How do you explain the web to people who have never used it? You make it as simple and as accessible as possible.

JoRoan Lazaro was a young designer who had double-majored in computer science and psychology until the second semester of his senior year, when he decided pursue a fine arts BFA, ultimately finishing both. “None of it really made sense back then, in the ’90s, until the internet came around,” he recalls. In hindsight, it was the perfect education for a UX designer—if UX had existed as a formal industry then.

After he accepted a job at AOL’s Northern Virginia office in 1996, Lazaro and two other young designers were tasked with designing AOL 4.0. All three had backgrounds outside of tech, and they approached the design process by pulling in insights from disparate disciplines of design. Lazaro designed the company’s now-iconic “Running Man” logo after being inspired by old books of hand-drawn trademarks from the 1930s and ’40s. “I was seeing that kind of style of people and logos for craftsmen or for electric companies that were very easy to understand and, in a way, very folksy, but communicated what the product and service were for,” Lazaro remembers.

For some reason, the little dude was just charming enough.”

The idea that a user interface could be friendly, even folksy, was unusual in an era when software was viewed a tool, plain and simple. Microsoft Word and other common computer programs were cold pieces of software; this was before the era of Clippy. The Running Man proved disarmingly human. “For some reason, the little dude was just charming enough,” Lazaro says. “It was a novel concept to have something friendly and accessible as an interface.”

The idea behind the logo informed the rest of the AOL design system. The icons featured him holding keyword objects: If you wanted to check your mail, you could click on him holding an envelope. To favorite something, hit the icon of him holding a heart. Lazaro, who had worked as a graphic designer and on magazine projects, let his experience telling stories guide the process, right down to a color palette that was alien in the cold, black-white-and-blue world of ’90s software. “I chose warmer earth tones—there were greens, oranges, and ochres in there,” he says. “I really want something that was friendly and not cold and not techy.”

Slack before Slack existed

The design team’s interface was a hit with young users, both inside and outside of AOL. “We thought that the animations . . . the buddy icon . . . [were] so cool,” Bosco says.

Meanwhile, AOL employees were using AIM at their desks—and proposing new features based on how they used the chat client during office hours. “We were using AIM internally for work, like Slack,” Bosco remembers. “So a lot of the innovation in AIM happened from just solving problems that we faced as users of the service.”

One early frustration emerged from a relatively common scenario: A coworker would stop answering their AIM, so you’d have to get up and walk over to the person to see if they were away from their desks or just busy. “This is dumb, we should automate this!” Bosco remembers thinking. They came up with the Away Message, a new feature that could automatically be posted if the computer went to sleep, or set up while the user was out at lunch.

We were working so much, and it was so busy, that you barely had time to really stop and think about it.”

At the same time, users even younger than AIM’s twentysomething engineers were driving its adoption: middle- and high-schoolers. “I think part of it [was] just the network effect—these kids who were using it, their parents were paying for AOL to get onto the internet,” Bosco says. “And so for them, it was kind of like what they had.” Lazaro points to the way young people use Google Docs today to chat during school. “You use what you’ve got—and it’s not even about rebellion or personal identities,” he says. “It’s just like, oh, here’s this thing. Let me use it to do the things that I want to do—which is talk to my friends.”

AOL and AIM—with its friendly interface and functionality that let people customize their avatars, away messages, and usernames—seemed tailor-made for an era when the internet was beginning to reshape young people’s ideas about digital identity and messaging.

rip, aol instant messenger (1997-2017) pic.twitter.com/auB3D7f3hr

— Tiny Cartridge (@tinycartridge) December 15, 2017

The dawn of UX

In the later years of the 2000s, it would become common to refine the minutiae of a product by testing and retesting it; Google famously A/B tested 40 shades of blue for its hyperlinks. But during the heyday of AOL and AIM, user experience design was a field still in its infancy.

User testing wasn’t commonplace when Lazaro and his coworkers were building AOL 4.0, so instead, they learned as they went. Before a full usability lab was established at AOL, they listened to customer service calls to understand how AOL users interpreted their work. It may have been low-tech, but it was an education on how people really used and understood the services they were designing.

“It was super educational for young designers like myself. Back then, I literally had blue hair!” he says, recalling his baggy jeans and the dance culture that flourished on the East Coast during those years.

The experience of designing for such a huge group of users was “eye-opening.” So was meeting some of those users in the wild—perhaps on the way home from a late night of dancing, talking to a cab driver who asked what he did for a living. “It becomes really real when people tell you that the thing that you and the team have designed and made is something that they use, and has so much meaning and value for them,” says Lazaro, who today is VP of product design at experience design studio Elephant.

“It’s heartwarming and meaningful and also very humbling that the thing that we were designing made such a difference in people’s lives, in that very simple way of just communicating,” he adds. “So it was really cool—but truthfully, we were working so much, and it was so busy, that you barely had time to really stop and think about it. So for me, it was those conversations with people out in the world that had the most meaning.”

The internet without AIM

AOL and AIM shifted the way people thought about the web: that users step away from the network momentarily, rather than stepping into it to communicate for brief periods.

“We were in a unique position working for AOL,” says Bosco, who today is global VP product for experiences at TripAdvisor. “This was the company that was the backbone of the internet. Outside of all of the AOL consumers, quite literally all of the business internet in the United States flowed through AOL data centers that we had in Virginia. We had a real sense that if there was a company in America at that time that was connected and fully on all the time, it was that company. And we saw the value of that.”

We had a real sense that if there was a company in America at that time that was connected and fully on all the time, it was that company.”

Slack, Gchat, and other platforms owe the idea of ambient communication to AOL. Of course, today, many users view that always-on mentality with a healthy dose of skepticism—where America Online’s creators never intended to create a culture of 24/7 work, the way other companies have optimized the messaging model for productivity has been sharply criticized by employees who feel controlled and surveilled.

What would the internet look like had AIM not become the dominant chat platform around the millennium? If the AIM team hadn’t fought to make their chat service free and interoperable, would a different messaging paradigm have won out in the 2000s? It’s hard to say. Companies like Google, Apple, and Facebook are still attempting to keep their messaging platforms as walled gardens that serve their larger, proprietary ecosystems. If AIM’s legacy is any guide, the most successful messaging platforms are the open ones.

“Eventually, people will want to talk to other people and other communities,” Bosco contends. “And those systems [that] make that seamless, across communities, are the ones that people tend to gravitate to over time.”

Read the rest of this series here.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.