Human innovation has long been inspired by other organisms, from the wild thistle plant that spurred the invention of Velcro to the kingfisher bird that helped engineers design bullet trains. It’s called biomimicry: looking to nature’s systems, designs, and processes for inspiration to solve human problems. So wouldn’t it make sense, then, that as climate change threatens to make our world inhospitable, with rising sea levels and intense heat, we could learn something from the way the earliest life forms survived when Earth had similarly harsh conditions?

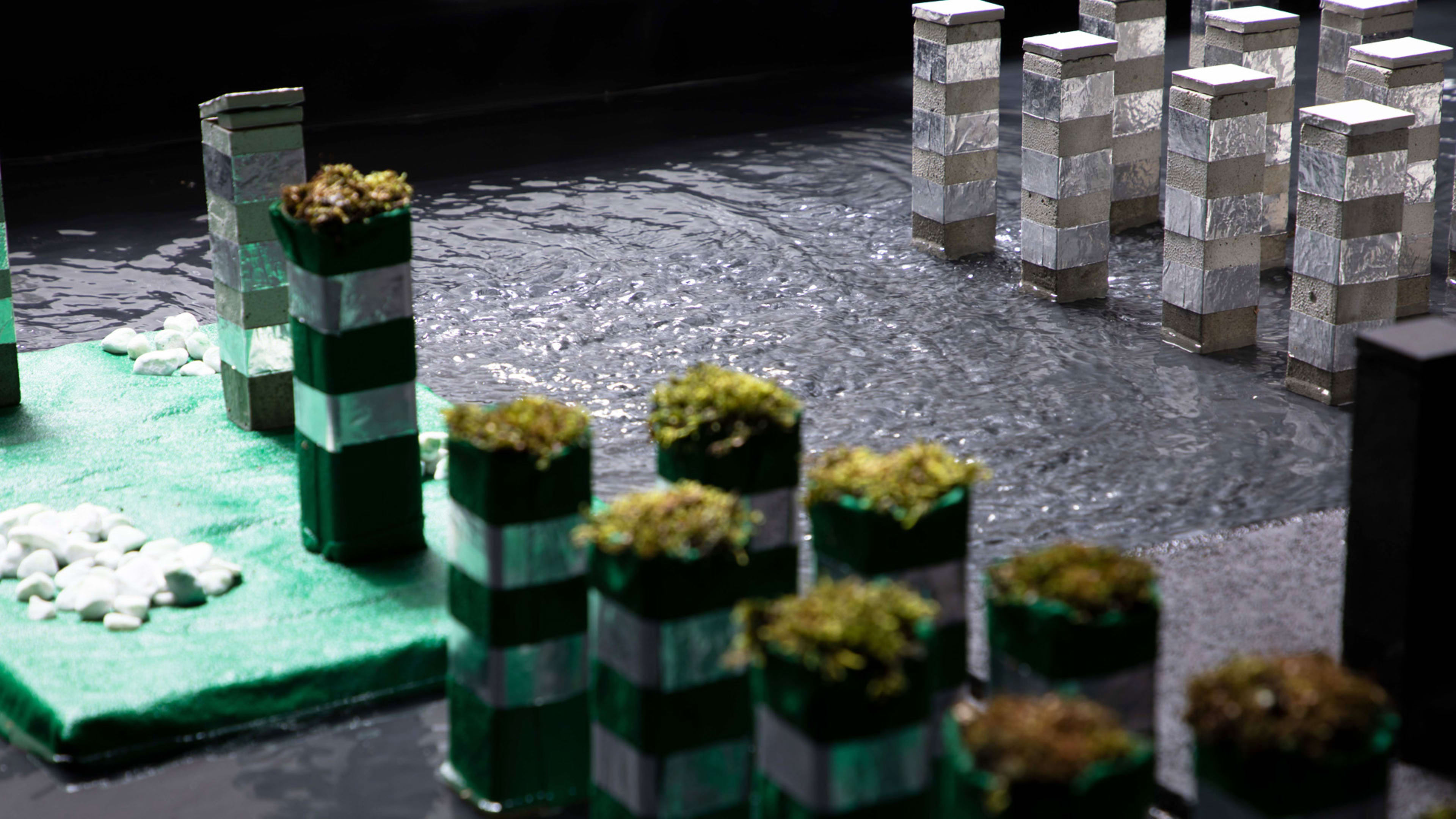

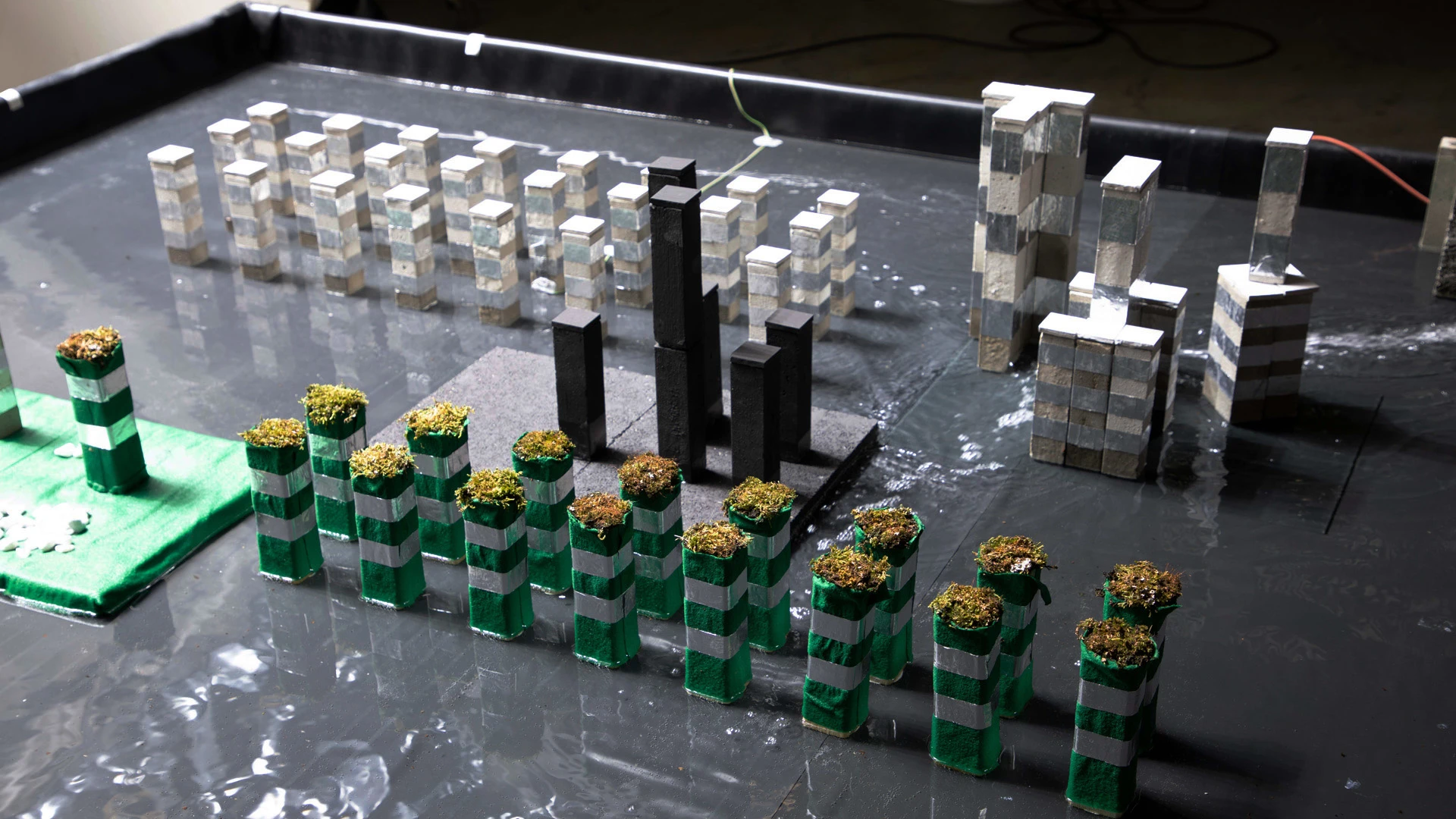

That’s the hope of artist and experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats. In a new exhibit called The Primordial Cities Initiative, which will open at STATE Studio in Berlin on December 12, Keats shares his “stromatolite cities” concept. Stromatolites, the fossil remains of early microbial communities, are made of layers of limestone, the remains of those single-celled organisms, and the silt they trapped from the water. Stromatolites, which are among the oldest record of life on Earth, proliferated in tidal environments.

As water levels rose, stromatolites grew, essentially “sacrificing” the lower layers to be an underwater foundation for new layers that rose above the ocean. As climate change threatens to submerge our existing cities, Keats proposes a way we could adapt to that new environment like stromatolites, rather than seeing inland migration as our only option of survival. In “stromatolite cities,” skyscrapers could be erected in the same way, with continuously layered construction that allows people to move to higher floors as water fills in lower stories.

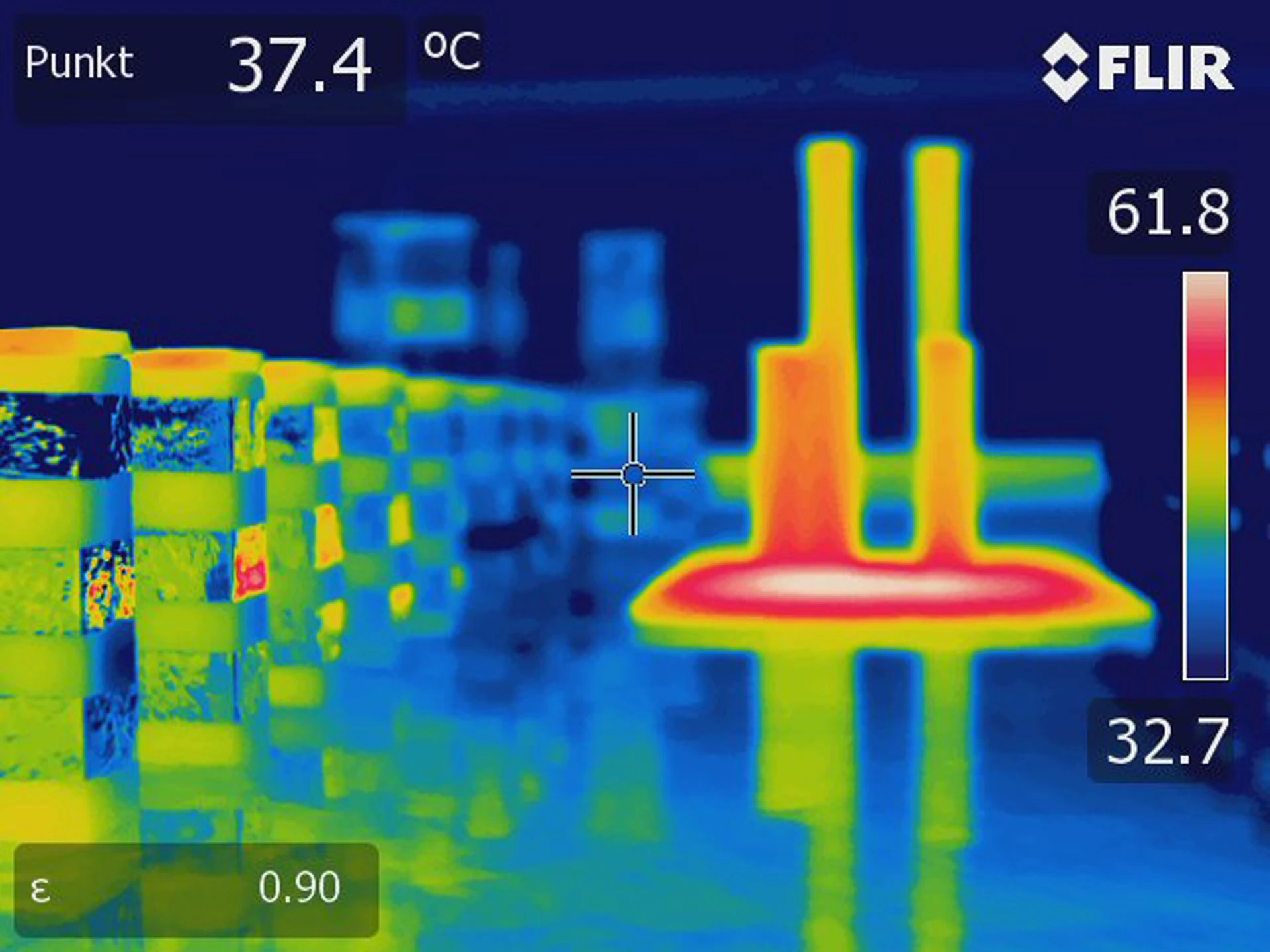

Living like stromatolites could also mitigate the urban heat island effect. “Stromatolites lived in these environments because they moderated a lot of these extreme conditions. There was a homeostasis provided by the tidal environment,” says Keats. Large bodies of water act as a heat sink, and can help conduct heat away from something like a stromatolite or a building.

“The idea then became to think about how we might build cities to take advantage of tidal environments, and to take advantage of them in a way that would help to address the overheating in cities and as a result of overheating, the increasingly extreme use of air conditioning,” he says. Not only will temperatures be mitigated by the surrounding water, but that water could also serve as an energy source, through both pump systems in the lower levels of buildings that are sacrificed to rising tides, and from extra solar energy harvested from the sunlight reflected off the water.

As with all his work, the stromatolite cities are based on theory, but one borne out by some hard science. Keats worked with researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics to create computer simulations that analyzed the cooling effect of flooding in districts of Shanghai, Manhattan, and Hamburg, three cities sure to be affected by rising sea levels in the coming centuries. The simulations projected the sea level rise and expected seasonal temperatures in the years 2100 and 2300, and found that the effects were made milder—and thus more hospitable to humans—by the evaporative cooling effect of the surrounding water.

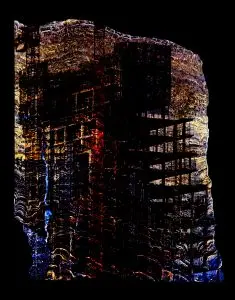

The exhibition will include the results from these Fraunhofer IBP experiments along with models of Keats’s stromatolite-inspired building designs: one made of concrete, with a hollow base that sits on a mast so it can float up and down with the changing tides; and one made of wood, which Keats says is like if you built “a log cabin as a skyscraper,” with a green roof to grow trees, which could then be used to build additional stories.

Keats doesn’t expect urban planners see his exhibit and immediately start drawing up plans. He’s realistic that this very likely won’t be what our cities of the future will look like, but he hopes that providing this alternate reality gets us all thinking, with more urgency, about our future, and what kind of future we want. “By showing a potential future like this,” he says, “it provides the ability for a conversation and debate for how we want to live, and how we want society to operate in relation to our environment.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.