For the past eight years, I’ve spent every day of my professional life enabling an industry that is responsible for nearly 40% of global climate emissions. I don’t work for an oil or gas company. I don’t work for an airline. I’m an architect.

The environmental impacts of the built environment are staggering. Although it’s become mainstream to discuss energy efficiency and advocate for minimizing those impacts, architects, engineers, and planners have yet to truly reckon with the magnitude and consequences of everyday design decisions. Not only do we burn fossil fuels to heat and cool most buildings, but construction itself is responsible for plenty of global emissions. Construction requires massive amounts of concrete, steel, aluminum, and glass—all of which are carbon-intensive materials. Their emissions extend up and down the supply chain, crossing property boundaries, economic sectors, and markets. While architects are not fully responsible for steel manufacturing or concrete production per se, there is a direct line from the material specifications that architects write to the steel mills of China, the coal mines of Appalachia, the brick kilns of India, or clear-cut forests in the Pacific Northwest or the Amazon.

It is time for the design community to come to terms with carbon and climate change—both the reality of our shared climate emergency and the very personal implications of the building industry’s role in perpetuating it. Only then can we do the hard work of connecting our climate concern with our day-to-day actions, transforming guilt into collective change.

Focus on carbon

Broadly speaking, there are two ways of measuring the emissions caused by buildings: operational carbon (the emissions associated with energy used to operate a building) and embodied carbon (the emissions associated with materials and construction processes throughout the whole life cycle of a building).

Programs such as LEED, Passive House, and the Living Building Challenge focus on decreasing the former—operational carbon. This is a laudable goal; after all, building operations account for 28% of global carbon emissions, and improving the energy efficiency of buildings through widespread electrification and through decarbonization of the energy grid is essential.

However, we’ve come to recognize that it is not enough for architects and engineers to focus solely on operational carbon. For decades, we have been ignoring the role of embodied emissions in global carbon budgets.

Embodied carbon from building materials and construction currently represents at least 11% of global carbon emissions, much of which can be attributed to just three materials: concrete, iron, and steel. However, that seemingly small slice of the full carbon pie can be misleading. Global construction is proceeding at an incredible pace—with roughly 6.13 billion square feet of construction each year and global building stock expected to double in the next 30 years. When we look at new buildings anticipated to be built between now and 2050, embodied carbon, also known as “upfront carbon” because it is released before a building is even occupied, is projected to account for nearly half of total new construction emissions. For practicing architects, engineers, policymakers, and anyone who cares about climate strategy, this should give us pause.

We have 10 years to radically decarbonize the building industry. Think hard about what that really means.”

In 2018, a special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), called Global Warming of 1.5 ºC, asked two pressing questions: How can the global community reach the 1.5ºC target laid out by the Paris Agreement, and what happens if we fail? The report has two major takeaways. First, it is still possible to meet our climate targets, but only with immediate and unprecedented action. Second, the world presented if we fail to meet this target, by even a modest-sounding half-degree, are bleak—widespread ecosystem destruction, financial instability, growing social inequity, conflict and unrest, the disappearance of landmasses and nations. The scenarios are so clearly articulated, the models so robust, and the science so well documented, that they have ignited new urgency to find pathways across all sectors to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement and accelerate our progress towards a 1.5ºC pathway. Unfortunately, we are nowhere near meeting these targets. Last week, the UN Environment Program issued its annual Emissions Gap Report showing the ever-growing gap between the actual carbon reduction of countries and those necessary to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Since 2010, global emissions have risen by 11%, and the gap between “where we are likely to be and where we need to be” has grown enormously. Countries and industries have failed to stop the growth of global carbon emissions, and now faster and more aggressive cuts are required.

All projections that give us a chance of avoiding catastrophic and potentially irreversible climate impacts mandate that we must radically cut carbon emissions immediately. The report makes the case for the urgent need for action, and also painstakingly lays out strategies that can help us bridge this gap, while also focusing on creating transformational change and just transitions. It is time for the building industry to act.

We have 10 years to radically decarbonize the building industry. Think hard about what that really means. We have a decade to fundamentally reshape our global economy. Fifteen years ago, we needed exemplary projects, to build capacity in our industry, to increase carbon literacy, to educate our clients. We needed case studies to show that net zero-carbon projects were possible. I’m sorry to say that we’ve basically squandered those years. Now, we need every project to dramatically reduce emissions if we are to stand a chance of meeting global carbon goals and averting the catastrophic effects of a 2º future.

The task is daunting, but not impossible. It does mean that we need all the skill and talent of this industry to care about carbon, to be as serious about climate change as we are about our professional responsibility to protect the health and welfare of building occupants or to protect the financial interests of our clients. We need to be as excited about decarbonizing the building sector as we are about making the tallest towers in the world, works of great cultural significance, or exquisitely crafted details.

After spending the bulk of my career jumping back and forth between the technical side of carbon modeling and the practical realm of architectural design, I’ve come to realize that our big challenge is not better data or complex modeling. Architects are adept at balancing a never-ending list of project requirements, values, and demands on our time and energy. Embodied-carbon analysis tools exist for nearly every design workflow. Environmental impact data continues to improve. Manufacturers are starting to do the work of material and chemical disclosure.

There are changes to policy and code on the horizon. The real challenge is design culture.

Transforming design culture

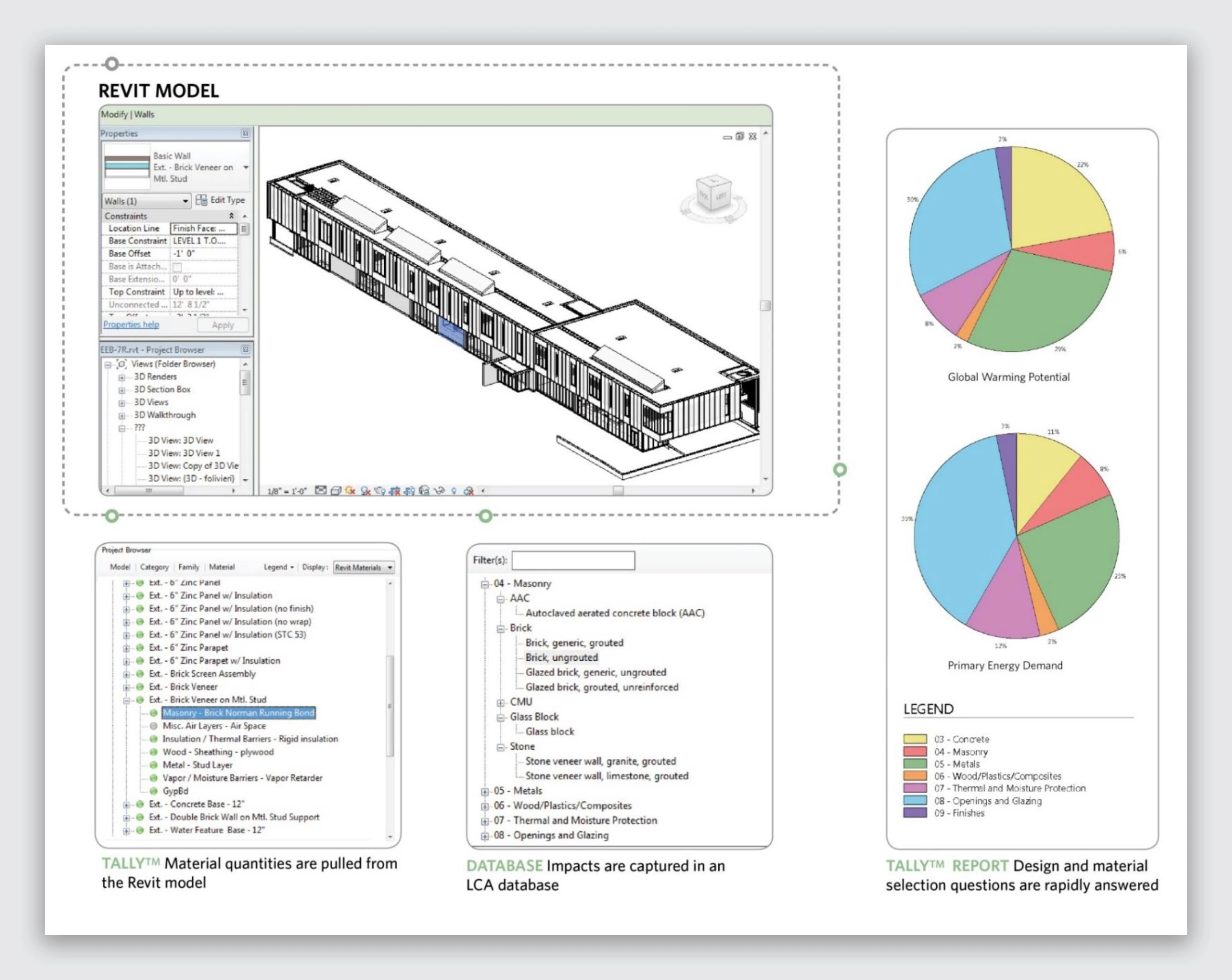

Let me tell you how our firm, KieranTimberlake, decided that we needed to take carbon and climate change seriously and how this desire has challenged our design practice. Roughly seven years ago, after three decades of sustainability-minded practice, we decided to get real about environmental impacts and embodied carbon. We educated ourselves on life cycle assessment (LCA), a method for evaluating the environmental impacts of a building or product over its full life cycle, from material extraction through manufacturing, distribution, construction, use, recycling, and final disposal. The practice of LCA has been around for almost three decades and is widespread across industries and sectors. It’s the international standard for evaluating the carbon footprint of everything from biofuels to blue jeans, cellphones to the entire meat industry. As we started to run LCA models of whole buildings, we found that while the software and methods existed, there was a real scarcity of tools built specifically for our industry and for a design workflow—we simply couldn’t integrate existing tools into our design process.

For life cycle analysis to be useful to designers, it must be capable of answering design questions and lead to measurable carbon reductions on real projects. Therefore, we needed a tool that was easy to use, that could be integrated into a design workflow, and that produced data at a speed and resolution that supported design decisions. When carbon information is not readily in the hands of design teams at the moment of decision-making, designers lose out on opportunities to reduce the carbon footprint of buildings in strategic and cost-effective ways. Designers can’t make informed decisions if they don’t have the information at hand.

There are changes to policy and code on the horizon. The real challenge is design culture.”

Unfortunately, such a tool did not yet exist. So, we set out to make the tool that we wanted to use on our own projects; we hoped others across the industry would also find it useful. After two years of development, we produced Tally, the first Revit-integrated LCA tool. Our principles and goals have remained consistent throughout the development of Tally: Make it easy, accurate, iterative, and clear. Tally is a plug-in for Revit, a 3D modeling and documentation software that most architects and engineers use to design and build complex projects. For many teams, having the ability to run carbon assessments natively within a design model was a game changer. It did away with the need for an outside consultant to construct an entire model for analysis purposes, an exercise that is inefficient, time-consuming, and prohibitively expensive for most projects. It also meant that teams could run iterative assessments, getting real-time feedback as design options are developed and evaluated.

While the development of building-industry-specific carbon accounting tools such as Tally have given architects and engineers the ability to consider both embodied and operational carbon on every project, you still need to convince design teams to make use of these tools. Once we began using Tally on our projects, we found that we could easily make embodied carbon reductions of 10-20% with simple design changes such as using low-cement concrete mixes, light-weighting the structure, or beginning to consider timber and other bio-based materials. Still, too many projects have little incentive even to try.

The real transformation happens when we run carbon assessments on every project. Not the special projects, not the LEED Platinum projects, not the ones where clients pay extra. Even in a firm that has dedicated years of research and development to furthering the practice of LCA across our industry, this has been hard. It has forced us not only to take seriously the technical aspects of LCA and building documentation but also to interrogate how design decisions are made. A tool is useless unless it is used. A low-carbon strategy is meaningless unless it is actually implemented, and the design proposal is actually built.

Low-carbon architecture is ethical architecture

So, what is the role of the designer in tackling carbon emissions? The goal is not to transform architectural design into an act of analysis. The real work now is to figure out how to make carbon assessments part of ethical and inspired design practice. The practice of architecture is already overburdened with modeling and simulation, with litigation, and with cost-cutting. However, I would urge every designer to consider that by failing to connect your concern over climate change to the impact of your day-to-day work, you are already expressing your values. You’re already saying that this is an issue that you don’t really care about at all. Climate change cannot simply be an issue we talk about only when it is convenient.

By failing to connect your concern over climate change to the impact of your day-to-day work, you’re already saying that this is an issue that you don’t really care about at all.”

It’s essential that architects improve their carbon literacy and find ways to engage in contemporary climate science, technology, and policy. It’s also essential that we bring our whole selves to this task. We need every designer to engage in reducing the carbon emissions of their projects, but also—in the process of applying our considerable knowledge of how cities are built, and our skills of communication, design, and storytelling—to improve the practice of carbon accounting and LCA.

Carbon modeling is a world of unintelligible emissions figures and endless stacked graphs, Sankey diagrams, and pie charts. It would be kind to call it a graphically challenged space. In addition to running high-quality and actionable analysis, designers also need to work on developing graphic and narrative techniques that express the nuance of our understanding of carbon emissions over the full life of a building: the timescale of carbon and the subtle ways in which material flows into and out of buildings over the course of their lifetime; and, perhaps more importantly, the ways in which grid electricity is decarbonizing over the life of a building, but the embodied carbon in construction is an ecological debt that we never get back. These are challenging concepts to communicate, and numbers alone are not enough.

Addressing the climate impacts of the built environment is about more than data and modeling. It is also about rendering transparent and understandable the hidden processes of extraction, industry, governance, and economics that have created this global catastrophe. While I am deeply conflicted about the millions of tons of carbon emissions that our buildings have caused, I also recognize the potential for architecture to enrich and support communities by creating places of learning, culture, healing, and shelter. The vision of a radically decarbonized building sector is possible, but only if we all work as if our future depends on it.

Stephanie Carlisle is a principal at Philadelphia architecture firm KieranTimberlake.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.