Eva Orner didn’t set out to make a #MeToo movie. But by the time she finished shooting Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator, which comes out on Netflix today, that’s what it had become.

“I already thought it was a very timely, interesting, relevant story that people would want to watch,” the Oscar- and Emmy-winning director says, over the phone. “And then after #MeToo broke, right in the middle of production, it was like, ‘Whoa, this has now become a different beast.’ It was the same story and I didn’t change the way we told it. But to me, it’s now a cautionary tale of how men got away with it.”

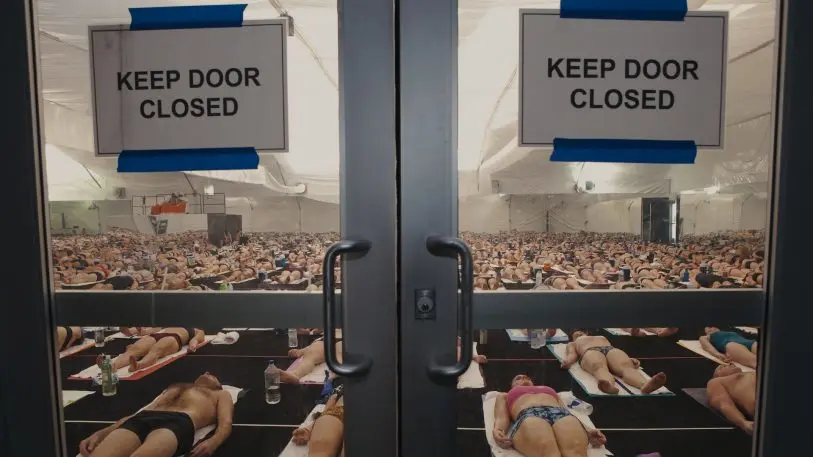

Bikram is a harrowing look at the man who introduced the eponymous, wildly popular style of yoga. Contrary to the appearance of the bendy discipline as a soothing balm of self-care, the film depicts how founder Bikram Choudhury created a hostile environment in his studios, rife with sexual abuse, and how he fostered a cult-like community around it to help keep his dark secrets.

Orner, who produced Alex Gibney’s Oscar-winning documentary Taxi to the Dark Side, first became aware of Bikram yoga, otherwise known as hot yoga, in the late nineties while living in Melbourne. A friend of hers asked the occasional yoga practitioner if she wanted to attend a class with her. Orner was interested, but when she saw a photo of Choudhury, famous for conducting classes wearing only his Rolex and a speedo, she begged off.

“Something about him bothered me,” she says. “A lot of my friends had gone and raved about it, and I knew the celebrity cachet and the Rolls-Royces and the lavish lifestyle and that Madonna had praised him, but I could tell it wasn’t for me.”

In order to get started, she had to bite the bullet and finally take those hot yoga classes she’d long ago spurned.

As she started to investigate the allegations against Choudhury, most of the people she wanted to speak with, including his accusers, asked her right away whether she’d ever practiced Bikram yoga. The community of trainers, and those training to become trainers, is tight and focused, and its members take it extremely seriously. Orner had to gain their trust by actively trying to understand the subject of all this devotion. Doing the poses in high temperatures made her feel fantastic, but what she found out once people started letting their guard down did not.

Once she learned more about the community from its members, she began to see why so many people within it were either protective of Choudhury or lived in fear of speaking out against him.

Ultimately, all the women Orner approached who had been abused by Choudhury were willing to go on the record and share their stories. Some of them had spoken out before, others opened up to her for the first time anywhere. One person the director was especially excited to get on camera is Jakob Schanzer. Having undergone a substantial weight loss through Bikam yoga, he is a physical testament to its transformative power. He is also, however, a testament to how the community remained silent about Choudhury’s abuse for so long.

“I felt like we needed a man to be able to say, ‘I knew. They told me this was happening and I did nothing,'” Orner says. “It was brave of him—not to diminish the bravery of the women who spoke out first. I don’t think enough men in the #MeToo movement come out and say anything like that. It’s interesting how many men say they didn’t really know, which is complete bullshit.”

Dating from long before the #MeToo movement took off, the victims of sex crimes have always had a particularly hard time getting people to listen to or believe them. Most cases without hard evidence come down to a he said/she said impasse, and that’s only when women rise above the potential shame of going to the police to actually report the crime in the first place. The system all too often fails these women. Bikram reveals how the criminal justice system in California mirrors that of New York City’s, where District Attorney Cyrus Vance mysteriously chose not to pursue charges against Harvey Weinstein for years, only caving in to pressure after the New York Times exposé. Aside from Choudhury himself, the villain that emerges in Orner’s documentary is California D.A. Jackie Lacey, who opts not to criminally prosecute Choudhury. (She also declined to be interviewed for the film.) In Bikram, Lacey comes to represent the legal hurdles impeding #MeToo’s progress at punishing men who abuse their power over women.

“I feel like we’re gaining ground, but I think there’s a long way to go,” Orner says. “And I think that a lot of men get away with it: the Charlie Roses and Matt Lauers. Those two got fired and that was kind of it. Sure, they lost their status and their fantastic lives and may have to sell their $30 million homes, but so what? They committed crimes. I think losing their position in life is huge for them because they’re very narcissistic, but I don’t think it’s enough.”

The director hopes her documentary inspires more women to speak up about their abuse to help hold predatory men accountable in the future. Beyond that, however, she takes solace in the idea of more people knowing who Choudhury is and just what he’s allegedly gotten away with.

“I hope [Choudhury] feels how many people see this film when he is gallivanting around the world, living his life,” she says. “I hope that when he’s in airports, people give him a hard time, and I’m hopeful that this will be so widely seen that it’ll have an impact on his life. I’m hopeful that every country he goes to, he’ll see people staring at him, cursing him out and challenging him for who he is. And I hope that takes a toll on him.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.