Capital & Main is an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political, and social issues.

Post-World War II America experienced both the continuing benefits of the New Deal and the consolidation of the American labor movement. During this period the wages of the lowest- and highest-paid workers rose together, while the share of the top 10%’s income decreased–validating a growing popular belief that, in John F. Kennedy’s words, “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

The New Deal, from which this relative golden age sprang, hadn’t begun as a visionary social blueprint so much as a series of laws, passed during the emergency of the Great Depression, that aimed to restore America’s battered prosperity by increasing employment opportunities, providing assistance to the elderly and dependent children, and establishing the rights of workers. In his first term, President Franklin Roosevelt strengthened banking regulation with the Glass-Steagall Act, provided jobs through the Works Progress Administration, and brought electricity (and economic development) to the rural South through the Tennessee Valley Authority.

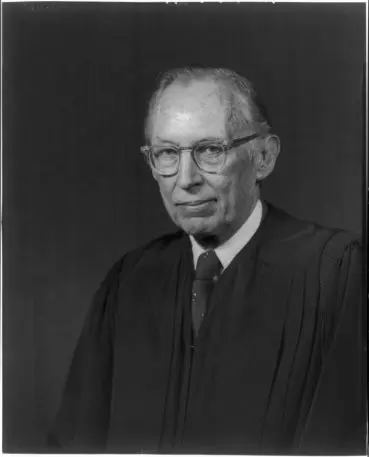

But by the early 1970s, beginning with a pivotal pro-business essay written by a Virginia corporate lawyer—and future Supreme Court justice—named Lewis Powell, things began to move in the other direction, inexorably so. Nearly 50 years later, the gap between the rich and the poor has grown. The wealthiest 1% are capturing an increasing share of the national income. The fortunes of the rich and the poor have diverged to the point that, in some places in the United States, there are levels of inequality reminiscent of the Gilded Age. How did this happen?

Many scholars blame trade globalization, foreign competition, or labor-reducing technology. But others point to people in power making conscious decisions. “Increasing inequality is a matter of choice: a consequence of our policies, laws and regulations,” wrote the economist and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in 2018.

Presidents, business executives, Supreme Court justices, and members of Congress made decisions to erode workers’ power, confer benefits upon the wealthy, and slash the social safety net. These choices happened together and within a system to disadvantage the poor and working and to reward the wealthy.

Economic inequality–especially the tearing of the social safety net woven by the New Deal—did not happen by accident. Nor did it all happen with the end of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs. Somewhere between the passage of the Social Security Act and the Powell Memorandum, a slow counterattack against the New Deal had begun to find its voice and its weapons; some of the seeds of the New Deal’s dismantling were sown during FDR’s four terms and, sometimes, by his own administration. New Deal benefits excluded vast majorities of black workers and women. The Social Security and Wagner acts (the latter of which established labor rights) consciously excluded agricultural and domestic workers, categories which represented two-thirds of black workers.

These exclusions created “a population that did low-wage work and was not protected by our labor laws,” says Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of Labor Education Research at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

Outside forces were also at work undermining the New Deal. In 1943, Florida passed the first “right to work” law that stifled the labor movement and created a template for other states to attack and weaken unions. In 1944’s NLRB v. Hearst Publications, Inc., the Supreme Court created a legal basis for contract work that opened the door to the temporary work economy that emerged over two decades later. Perhaps the most destructive of these early attacks on unions came in 1947 with passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, which limited labor’s ability to organize strikes and engage in political activity. The bipartisan law, which passed over President Harry Truman’s veto, was the start of the modern anti-labor movement in America.

Early milestones on the road to economic insecurity

1949—Algoma Plywood & Veneer Co. v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board. An era of anti-labor court rulings begins in earnest

The U.S. Supreme Court consistently upholds laws that reduce union power and strikes down or weakens laws that strengthen unions. “Every time Democrats would gain a little bit of power, they would try to introduce legislation to help workers,” says Todd Tucker, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute. “But then the Supreme Court would knock it down or would make an interpretation that would weaken it after the fact.” Most cases result in the high court chipping away at labor.

“Management rights superseded everything,” adds Bronfenbrenner. “The only thing unions were allowed to bargain over were the effects, not the decisions.” Prominent subsequent cases include Retail Clerks Local 1625 v. Schermerhorn (1963) and Davenport v. Washington Education Ass’n, 551 U.S. 177 (2007).

The Great Society represents the height of the U.S. welfare state. Johnson establishes Medicare and Medicaid to provide medical insurance and care to some of the neediest Americans. He strengthens civil rights and education access.

1968–Federal minimum wage buying power peaks at $9.90/hour in today’s dollars

1970–Richard Nixon reduces the corporate tax rate

Corporations have become so influential because they get to keep more of their money, “which means that they can invest more in lobbying,” says Tucker. After Nixon, most administrations reduce the corporate rate and the rate for the wealthiest Americans, resulting in a greater tax burden on middle-class and wage-earning taxpayers.

“[Powell’s] saying, ‘Our institution is under attack. Business really has to reassert itself or we’re gonna lose this thing,'” says Colin Gordon, a professor of public policy, political economy, and history at the University of Iowa.

Powell, a future associate justice of the Supreme Court, urges the Chamber to launch a coordinated effort to thwart “communists” and “leftists” who decry the free enterprise system. He sends this memo two months before his Supreme Court nomination–a series of events uncovered years later by journalist Jack Anderson. “This is an important document of business reasserting itself,” says Gordon, “at what we would call the dawn of the Reagan era.”

1978—Senate Republicans defeat Taft-Hartley reform

Utah Senator Orrin Hatch leads the effort against amending Taft-Hartley. He describes the bill as “a loaded organizing gun [aimed] at the throats of small business” and warns of the cost of mass unionization. Labor holds rallies to pressure the Carter administration to pass labor-law reform and strengthen the ability of unions to collectively bargain. “It’s the federal government backing you off the commitment it made in 1935 to majority rule unionism. That’s the big change,” says Gordon.

The modern foundations of inequality

1980–Jimmy Carter signs the Motor Carrier Act

The act deregulates the trucking industry, allowing thousands of small firms to spring up. This results in lower industry costs but will also decimate the industry’s unionized workforce. Heralding an era that will lead to corporate monopolization, Carter begins a wave of deregulation that continues into the Reagan and Clinton administrations with the Bus Regulatory Reform Act of 1982, the Trucking Industry Regulatory Reform Act of 1994, the Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 1998, and the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Most industries will see a contraction in the number of firms, the neutralizing of organized labor, and a reduction in wages, along with price cuts for consumers.

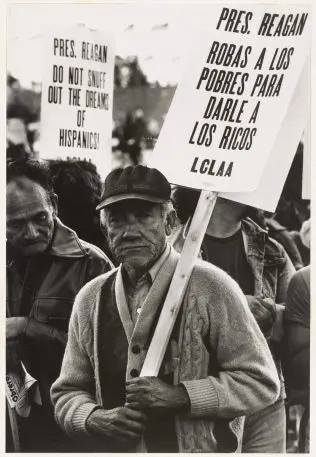

The Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1981 made hundreds of thousands of families ineligible for Aid to Families with Dependent Children and contributed to an increase in poverty. The budget allocation for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development was cut 74% during the 1980s. “One of Reagan’s most enduring legacies was the steep increase in homeless people,” Occidental College professor Peter Dreier would later write in Newsday.

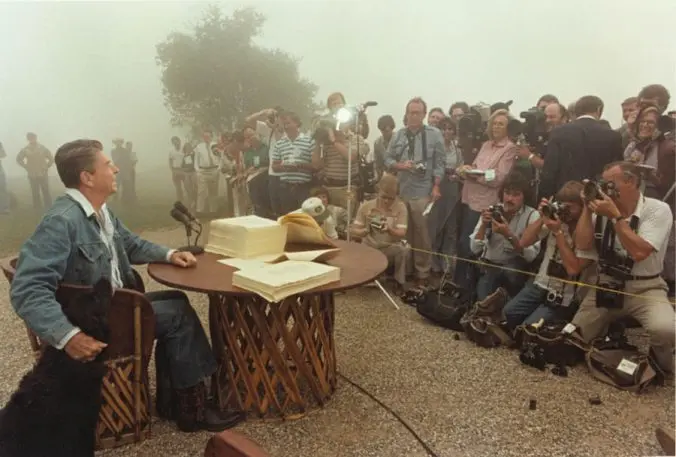

1981—Ronald Reagan breaks the PATCO strike

President Reagan ends one of the most public strikes in U.S. history by destroying the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, which had supported him in the 1980 election. Although the walkout violated an anti-strike clause in PATCO’s contract, Reagan’s firing of more than 11,000 striking employees signals to private- and public-sector unions that labor strikes are no longer the fearful threat to management they have been.

1981—Corporations increase their lobbying power by 1,300% in 10 years

Ten years after the Powell Memorandum, 2,445 companies employ D.C. lobbyists, compared to 175 in 1971. According to Tucker, the need for members of Congress to raise greater amounts of money for re-election races led to an increased reliance on corporate donors at a time when corporations began to outspend labor.

“As a lobbyist, you’re getting a phone call at 4 p.m. from a member of Congress asking for a campaign donation,” says Tucker, “and then at 5 p.m. you can be with the person’s staff, as a lobbyist, and help write the legislation.”

Reversing mid-century policies that favored heavy taxation of the rich, Reagan’s tax cut—one of the largest in U.S. history—slashes the highest tax rate from 70% to 50%. Reagan will reduce the top bracket again later in his presidency.

Gordon notes the tax cut marks “the redistribution of the tax burden from the high end to the middle.”

1981—The SEC legalizes stock buybacks

A shareholder revolution leads companies to redefine and prioritize their stock value as an indicator of a successful company. With stock buybacks now legal thanks to the Securities and Exchange Commission under Reagan, companies are incentivized to use profits to increase their stock prices, rather than reinvesting in research and development, or distributing earnings to employees through bonuses or salary raises.

Stock buybacks have been proven to reduce the share of income given to employees and to increase income inequality, according to new research by Katy Milani and Irene Tung from the Roosevelt Institute and the National Employment Law Project, respectively.

1983—Union membership stands at 20.1% of the American workforce

From the Taft-Hartley Act to Supreme Court decisions to state laws, years of assaults on labor converge to weaken America’s unions—whose peak year, 1954, saw membership reach 28.3% of the U.S. workforce.

Reagan budget director David Stockman is one of the strategic masterminds behind supply side economics, the belief that a reduction in taxes will generate widespread prosperity for all. To balance the budget in the wake of Reagan’s massive tax cuts, Stockman sets out to cut both social services and subsidies to corporations. However, due to the lobbying power of large firms, programs like the export-import bank, which finances trade, will remain. The poor’s safety net begins to shred as poverty programs, including food stamps, are slashed.

1990s and 2000s

1994—The North American Free Trade Agreement

Negotiated by the administration of President Bill Clinton, NAFTA reduces tariffs and creates greater trading partnerships with Mexico and Canada. NAFTA’s opponents claim it will “give management a new tool to lower wages because the workers are in competition with people abroad,” recalls Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Lichtenstein adds that NAFTA establishes the principle of capital mobility, which makes it easier for companies to change locations and avoid high costs. And it gives companies new tools in collective bargaining. Management, says Lichtenstein, can now “threaten to move if workers don’t keep their wages stagnant or even don’t take a pay cut.”

1996–Bill Clinton and Republicans’ welfare reform cuts program benefits and participation by families in poverty in half

Clinton replaces the Aid to Families with Dependent Children with the Temporary Aid for Needy Families program. Welfare reform significantly cuts cash aid to the poor and shifts the supported population from everyone in need to focus instead on workers with children. “You have to be working and you have to have a kid to qualify for most of these benefits,” says Gordon. “If you’re struggling and you’re a childless adult, you’re out of luck.”

Federal legislation raises the minimum wage from $4.25 to $4.75 in 1996 and to $5.15 in 1997. It won’t be raised again until a decade later.

1999—Clinton and a bipartisan Congress repeal key provisions of Glass-Steagall, a New Deal banking regulation law, contributing to the “too big to fail” problem

The 1933 Glass-Steagall Act regulated United States banking, but starting in the 1960s, federal regulators liberally interpreted U.S. statutes and allowed banks to take part in activities that the law prohibited in order to insulate commercial banking from investment activity. That move increased the power and importance of the financial sector of the economy as the country’s dominance in manufacturing waned. “Between 1970 and 2010, who [comprises] the 1% changes dramatically,” says Gordon, “It used to be all CEOs and managers. Now, it’s almost all [people in] finance.”

Deregulation of the banking industry allows the rich to amass even greater wealth and, many argue, the repeal of Glass-Steagall exacerbated or even led to the 2008 financial crisis by creating too-big-to-fail financial institutions that required government bailouts.

2001—Tax cuts championed by George W. Bush contribute to ballooning deficit, income inequality

Enacted in 2001 and 2003, the Bush tax cuts were intended to pay for themselves but instead became a large driver of the federal deficit. In 2010, the year they were fully phased in, the top 1% of households saw their after-tax income grow by 6.7%, while the middle 20% of households saw a 2.8% rise. Meanwhile, the bottom 20% of households received only a 1% increase in their after-tax income due to the tax cuts, according to the Tax Policy Center. The Bush tax cuts also eliminated the estate tax in 2010, though it was reinstated with a lower rate and higher exemption level in 2011.

Today

2017—President Donald Trump and Republicans pass the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Trump reduces the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, lowers the tax rate on capital gains, and increases the exemption for the estate tax to estates up to $11.2 million. The wealthiest 1% receives nearly a quarter of the act’s benefits.

2018—Janus v. AFSCME Supreme Court ruling strikes at unions

The 5-4 high court decision rules that the collection of union fees from nonmembers constitutes a violation of the First Amendment. The two largest public-sector unions soon see huge membership drop-offs, signaling trouble for one of the labor movement’s last strongholds, public-employee unions.

“The Janus decision,” says Tucker, “makes it very difficult for unions to retain their members. It makes it harder for them to collect fees, so it makes it harder for them to exist.”

Sources

In addition to material from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Congress, and other primary sources, the following were cited or interviewed for the timeline.

Introduction & 1940s: John Schmidtt, Colin Gordon, Estelle Sommollier and Mark Price, Joseph Stiglitz, Brad Plumer, Kate Bronfenbrenner, National Right to Work Foundation, Nelson Lichtenstein, National Labor Relations Board, Helen Dewar and Edward Walsh, Todd Tucker.

1960s: Colin Gordon, Matthew Michaels, Kimberly Amadeo.

1970s: Reclaim Democracy, Colin Gordon.

1980s: Brian Craig, Yes! magazine, Todd Tucker, Brookings Institute, Colin Gordon, Kimberly Amadeo, Katy Milani and Irene Tung, Adam Barone, William Greider/The Atlantic, Nelson Lichtenstein.

1990s: I.M. Dessler, Colin Gordon, Gary Stern and Ron Feldman, Kimberly Amadeo.

2000s: Emily Horton, Zachary Goldfarb, Kimberly Amadeo, Matt O’Brien, Todd Tucker, National Right to Work Foundation.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.