At the peak of puberty, glum young romantic Justin McLeod made a lifelong decision. “I was totally in love with this girl in seventh grade, and she broke my heart,” he says. “From then on, I was just like, ‘I’m never going to let that happen again.'” He resolved to put up an emotional wall to avoid a repeat of that torturous heartbreak and vowed to never again leave himself vulnerable.

When I visit the Manhattan offices of Hinge on a late afternoon in September, fresh andouille sausage and red potatoes are laid out for the staff, Cajun aromas wafting through the lobby. It’s all part of the startup’s monthly “Culture Club,” when the team comes together for a communal meal and some entertainment. The New Orleans theme explained the crawfish boil, which was bubbling in the reception-turned-kitchenette, and the Mardi Gras beads strewn across the office—and hanging off the back of one of the resident office dogs.

As office perks go, gumbo and bring-your-dog-to-work aren’t that unusual for a young startup. But the 55 employees at Hinge’s Greenwich Village office enjoy a more striking benefit that’s all too fitting for the online dating app: a monthly $200 dating stipend for each employee to use on any date, whether arranged via Hinge, or IRL. After all, the app is simply a means to an end, insists McLeod, who founded the app back in 2012. It doesn’t define romance—and neither does the classic meet-someone-cute-in-the-grocery-store-aisle hookup, or whatever form the initial chase takes, he tells me. McLeod’s wife has just had a baby, and that, for him, is the true definition of romance. The way you meet is beside the point, which is remarkably honest for the founder of the fastest-growing dating app in the Western market.

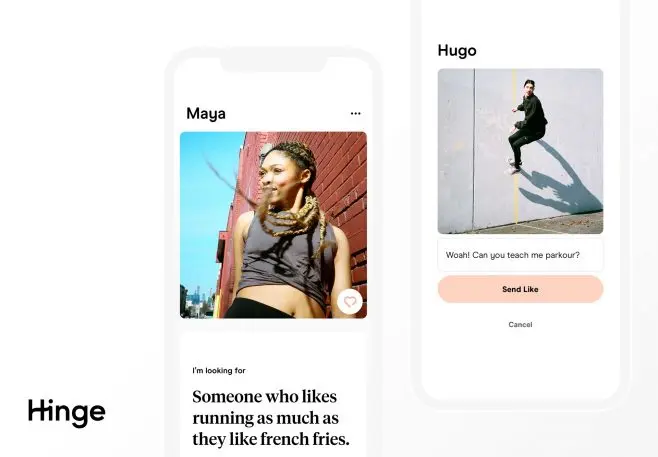

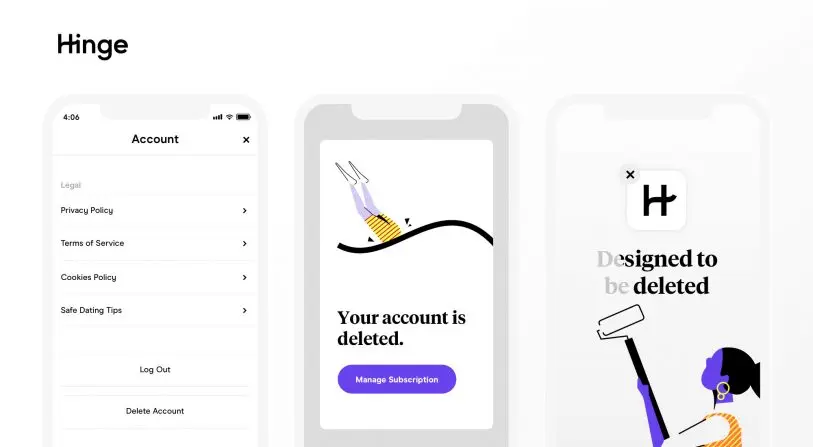

No romance in the chase is a curious conviction for a man who spent eight years pursuing his sweetheart. Besides, that pursuit was IRL, not online; McLeod doesn’t even use social media these days. Unlike his swipe-centric rivals, McLeod doesn’t want his user base to stay endlessly glued to the app. That’s why Hinge is “designed to be deleted.” The founder outlines Hinge’s two roles: one, it’s the chivalrous knight protecting users against tech addiction; and two, it’s the omniscient dating expert.

The expertise stems from a deep harvesting of data. It might not be the sexiest aphrodisiac, but it’s intended to give users insights into how to find a partner and erase the app with efficiency. The strange bedfellows of data and romance are increasingly defining McLeod and his app. After all, the two most notable events on Hinge’s timeline are the launch of Hinge Lab, the company’s new data offensive; and the recent release of Amazon’s new TV show, Modern Love, which includes an episode based on McLeod’s own love story.

His story is a godsend for one of Amazon Studios’ eight episodes of Modern Love, a new anthology series based on the New York Times column. The way McLeod—not Amazon—tells it, his love epic began in college, where he met Kate. They were seemingly polar opposites: she had never had a drink or kissed a boy; he was dependent on alcohol and drugs. But they embarked on an extraordinary relationship. Still, the couple made the heart-wrenching decision to separate to save Kate from what he saw as his corrupting influence. McLeod spent the final moments of his college career in rehab; he cleaned up, graduated, and swore to never touch drink or drugs again.

Four years later, he was on the cusp of graduating from Harvard Business School, with a pipeline into a job at McKinsey, and in a new steady relationship, when he realized he wasn’t happy. “No one compared to Kate,” he tells me. “I just couldn’t get her out of my mind.” He broke up with the woman he was dating and emailed the long-lost Kate. But she was living in London, happily seeing another man. “I was so heartbroken,” he says. “I think, in the back of my mind, I always thought Kate and I were going to get back together in the end.” But he’d waited too long.

It was over, and he needed to move on. But for a reformed man, free from substance abuse, spending nights in Boston-area bars to meet women was a surefire way to relapse. So, instead, he built Hinge.

Designed to be deleted

Because of his past struggles and tendency to get hooked, McLeod doesn’t have social media on his phone. “I know what addiction feels like,” he says. He has Audible and Spotify and Uber, “because there is some technology out there that is better than IRL,” he says. That’s his smart transition to Hinge.

The app is “designed to be deleted,” into the black hole to which McLeod’s Instagram, Gmail, Slack, and other past digital relics have been relegated. This brings him to the first of Hinge’s two roles, the cautioner of tech addiction, which he approaches with a tinge of tough love. “How would your life look if you weren’t sucked into Instagram, Facebook, Netflix—all these things that are designed to just take your attention?” he asks me. “Imagine looking back on your life when you’re 80 years old, and you’re like, ‘Wow, I’m so glad I spent two-thirds of my waking hours staring at a screen and moving pixels. I lived a full life.'”

Tinder is owned by online dating monopolist Match Group, which also fully acquired Hinge in February. But he doesn’t see the two as competitors. While Tinder has doubled down on unapologetic hookup culture, using slogans like “single not sorry” and “single does what single wants,” Hinge has found its lane in meaningful relationships, and its mantra has become “find love, dump us.” He puts more credence in psychographics than demographics, in the shared intention to find a significant bond with a significant other—and that outlook spans age groups. The app is surprisingly fastest growing among younger people, he says, aged 22 to 26. “It’s universally felt that people want deeper connections,” he says, “as opposed to the endless, superficial, one person after another.”

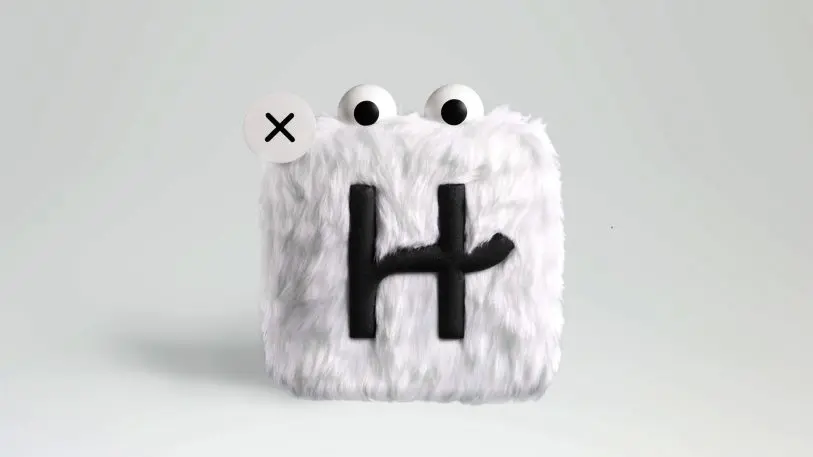

In an extension of that business model (or gimmick, skeptics may say) of sacrificing itself for the greater good of love, Hinge has personified itself into a mascot and murdered it. Its latest brand marketing campaign, appearing on subway billboards and TV spots alike, introduces the character of Hingie, a cute and cuddly embodiment of the app icon, tragically meeting its necessary demise in the background as couples fall in love.

On a broader level, McLeod says Hinge arranges 200,000 dates a week, translating to a date every three seconds. Three out of four first dates turn into a second date. This is precisely the type of data Hinge wants to accrue.

The data behind desire

That’s why McLeod is in the rudimentary stages of setting up a brand-new data department, Hinge Lab. It’ll comprise a data scientist, to extract the information from successful users, both scientific and anecdotal, and a research team, to pull valuable insights from the data to find out what’s working. How often were they using the app? How many likes per day were they sending? Were they selective about replying?

Hinge Lab will pair with marketing to transform the data into articles and advice, and with product, to fine-tune the algorithm and innovate features based on findings. “We want to be the really solid advice that you can trust because we actually research this,” McLeod says. Informed by the data, Hinge can then wear its other hat as the enlightened dating expert. The ultimate goal: “We will be able to develop the ability to help predict what type of person you should be with that will generate a likelihood you’ll stay together and a likelihood you’ll be happy.”

After all, Hinge has already extracted the insight that 81% of users aren’t fully confident they’re putting their best foot forward and that 88% of users are interested in some help from Hinge; 38% of men are not confident in turning conversations into dates, and 43% of women are not confident in assessing compatibility. So, Hinge will be personal trainer of the dating world. “A dating app is kind of like a gym,” McLeod says. “Hinge Labs is going around, looking at all the buff people in the gym and being like, ‘what are they doing right? And how can we bring those learnings to everyone?'”

“I would say none of us are good at dating, naturally,” McLeod says. It’s likely that belief is a reflection of his own very tempestuous journey to finding love.

His own relationship? “It’s complicated”

In the interest of moving on, if schmoozing in bars wasn’t the right fit for McLeod, nor were the apps that existed in 2011. For young people, finding love online was stigmatized. “OkCupid was so embarrassing,” he says. “I just could not bring myself to do it.”

To be sure, Hinge wasn’t always down to sacrifice itself. McLeod started working on his app in February 2011, and in the early days, Hinge’s UI fell in line with Tinder’s. The established online dating platforms, Match.com (launched in 1995) and eHarmony (2000), which required detailed profiles about hobbies and interests, were strictly for older people and so uncool. Apps, which appeared after the advent of mobile and Facebook, had to appear casual in design, and swiping left and right checked that blasé box. Tinder launched in Fall 2012, and its success was the litmus test for the rest because it was incubated at and launched by the sturdy Match Group. Previously dubious investors started to flock in.

McLeod himself was in a daze, romantically speaking. In a 2014 New York Times piece on Hinge, when asked about his own relationship, he said, “It’s complicated.” Kate still wasn’t out of his head.

The following year, the Times returned to McLeod for another story on the burgeoning business. He was visited by journalist Deborah Copaken, who asked him if he’d ever personally been in love. Thus began McLeod offloading his pang-filled story about Kate. Copaken immediately related, sharing her story of a similarly long-lost love. “You have to tell her,” Copaken reports she told her newfound, moonstruck mentee in what became her Modern Love column. She urged him to go get the girl–in person.

He followed orders and flew to Europe to confess his love to Kate. “She was to be married in a month,” Copaken wrote, “but three days later, she moved out of the apartment she had been sharing with her fiancé.” Soon enough, McLeod married Kate, and they now have a baby together, and the rest is history–history that’s being retold in Amazon’s adaptation of his story in Modern Love. Sort of.

It’s a very loose adaptation, and less captivating than the actual story. Amazon’s is more schmaltzy and PG-13, eschewing McLeod’s drug-abuse past in favor of a clean-cut Dev Patel (who shares McLeod’s disarmingly charming smile) dishing out corny metaphors about leopards at the zoo. Rather, the focus is Catherine Keener’s “prying journalist” playing Cupid and goading Patel to go after his soul mate.

In the end, McLeod didn’t use the app he built for himself to find love. But his drawn-out courtship and eventual catharsis did serve as a eureka moment for the direction of his business. In 2015, he decided to tear the app down and rebuild it from the ground up. The dinner party philosophy was well and good, but ultimately, he was still playing Tinder’s game. “Unless we pivot to a different market, there’s not going to be a lot of headroom for us to grow,” he says.

So, the reboot focused on something he’d been avoiding since his seventh grade heartbreak but that had eventually been instrumental in clinching his dream—vulnerability. Tinder was a numbers game, where users were betting on finding a match after never-ending swipes. “You like someone, but you only find out if they like you back,” he says. “It just turned into a game in a casino.” Rather, McLeod realized, it was time for love-seekers to put themselves out there. “It’s about vulnerability and opening up and softening your edges.”

That informed the de-Tinderization of Hinge and the ultimate user goal of deleting it. Hinge no longer conforms to the swipe template, so anyone can talk to anyone who pops up on their feed, without having to “match” first. As a nudge in the direction of candidness, users now have to answer a choice of three prompts that encourage sensitivity. They may elect to disclose “the dorkiest thing about me,” or “a shower thought I recently had,” or, to cut to the chase: “I’ll fall for you if . . .” They’re designed, McLeod says, “to get you to open up in a way you wouldn’t have got to until the second or third dates,” and with “a trajectory towards getting off the app.”

The same theory applies to photo selection. McLeod suggests picking photos that lend themselves to a conversation. “A hot, filtered selfie—how do you connect with that?” he asks. “‘Super-cool shades, dude’?” This attitude is tied to his rebuke of social media; his method is about getting away from the rules of Instagram and seeking scores of “likes” on buff beach snaps. “We’re fed on the junk food of validation,” he says. “But if you want a connection, you’ve got to be vulnerable.”

Vulnerability seems to be paying off, in business as in love. Globally, Hinge downloads more than tripled year on year in the second quarter of 2019, and it’s currently the fastest-growing dating app in the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Australia.

So, he’s happy to show complainers the door. Hinge loses 20% of people during the signup process, McLeod says. “We’re filtering out the 20% of people who do not care enough to even fill out a few prompts and select a few thoughtful photos and philosophy about themselves,” he says. It’s better for the algorithm to have a collection of people who are equally willing to put the effort in. “And, if you don’t care enough to do that, you’re not ready for the level of kind of connection and relationship that we’re helping you get.”

After our interview, Culture Club is in full swing, delivering the scents and sights (more beads) of The Big Easy. The team graciously offers to make me up a plate of food, but I settle for a tour of the office and some conversation. An employee tells me she’s soon heading to New Orleans for a friend’s wedding, for which the couple is set to have the iconic bustling brass-band parade. As we discuss the nuptials, no one asks where the couple met–online or IRL. In the end, it hardly matters.

Whatever the means, McLeod’s tough-love rationale for his reboot still applies, philosophically, to all relationships—whether kindled on Hinge or IRL or, of course, during eight years of lovelorn languish. “Do you think it’s effortless to find the most everlasting happiness of your life?” he asks. “It’s hard. And it should be harder, in my opinion.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.