Evie Powell is a virtual reality engineer and the lead UX designer for Proprio, a surgical imaging company that fuses human and computer vision to create a powerful system for surgical performance and training. She spoke to Doreen Lorenzo for Designing Women, a series of interviews with brilliant women in the design industry.

Doreen Lorenzo: When did you first realize you were interested in design?

Evie Powell: I spent a lot of time as a kid deeply engaged with my computer. I started out with simple arcade games, the Pac-Mans, the Marios, and all of that. Then in middle school and early high school I played Japanese RPGs that involved developing a character from a very low level. I eventually started playing games that were only released in Japan and that got me into learning Japanese when I was in college.

As an introvert attending the Game Developers Conference for the first time, participating in a business-card trading game is what shifted me into a different mindset where suddenly, talking to people to collect and trade business cards was something that I really wanted to do. That’s where my research into games really started to take root and direct my career trajectory.

I did my PhD at UNC Charlotte on socially pervasive game experiences, where my research was focused on how to create a game that never really turns off. I studied how computing would change and how I thought design—specifically software-engineering design and software user-experience design—would have to change as computing becomes increasingly ubiquitous and contextually aware. As computers have gotten smaller and more powerful every year, the capabilities they enable and the way we think about computing have fundamentally changed. It’s like having a library at your fingertips. And games are no different—we use games and play to learn better. Games structure how we gather information and potentially learn and create new things. So how do you create a game with no spatial, temporal, or social boundaries? What does that mean for the person who’s making the game, and what does that mean for the user? That’s what my research was about.

DL: What led you down the path from gaming to healthcare?

EP: After my PhD, I ended up working on natural user interfaces and the Kinect technology at Xbox. Ultimately my research in games always had a focus on helping people learn, play, and experience things differently by shifting mindsets. In healthcare, anticipating how a surgeon needs to think and designing a suite of tools to empower them to think and perform optimally is a great next step for me and my research.

DL: Tell us more about what you’re working on now at Proprio.

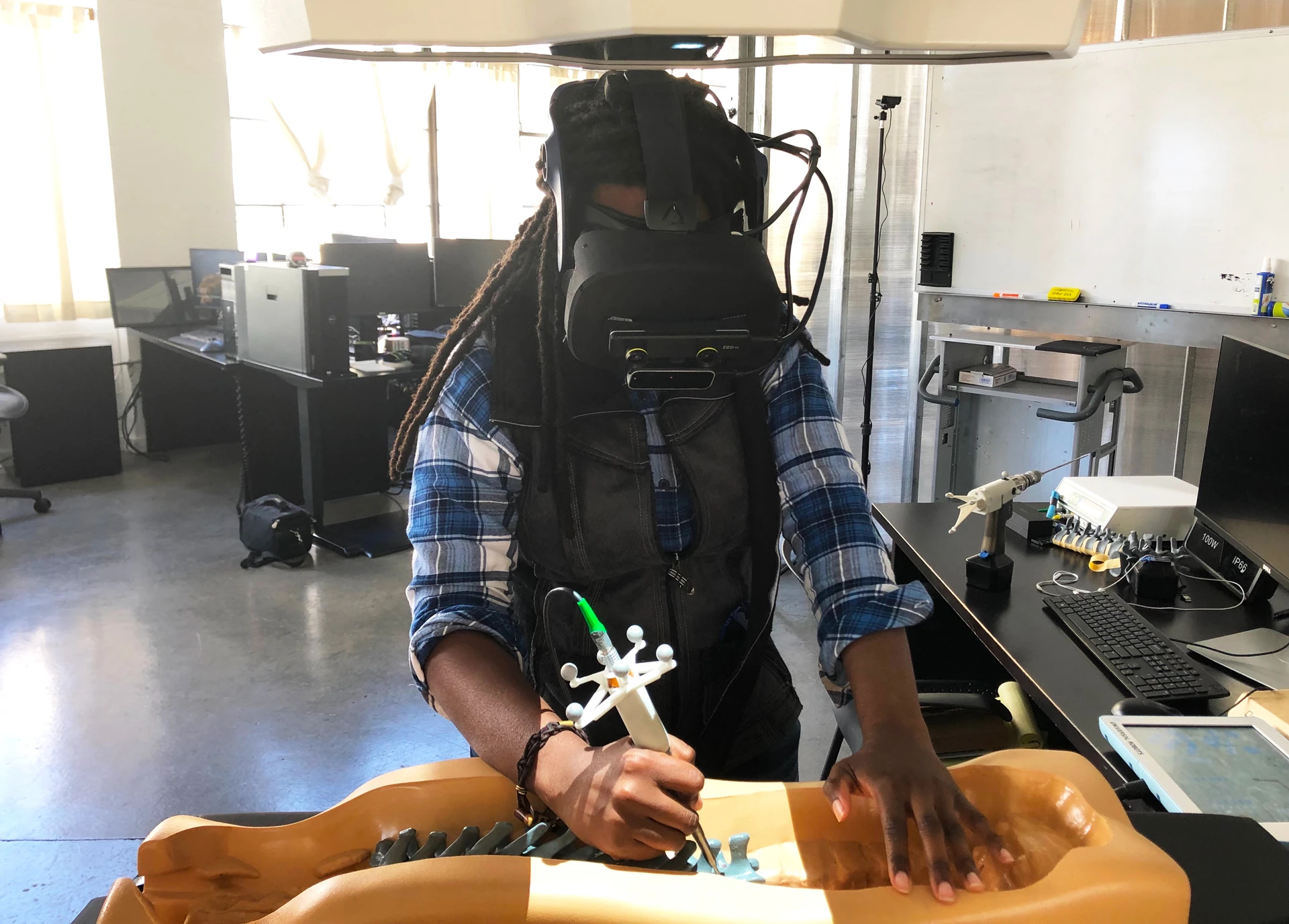

EP: We’ve built a robotic surgical system, which is guided by many cameras and sensors that can focus on a surgical site and create a digitization of whatever surface anatomy you’re looking at. In a process called light-field rendering, we capture light data from multiple directions and use it to provide a physically accurate representation of the scene for the surgeon to interact with in VR from every possible viewpoint. This real-time representation can also be fused with preoperative imaging and other patient data to further enhance a surgeon’s vision in the operating room.

You could think of this as the next generation of a microscope. Usually a surgeon has to press their head up against the microscope lens in order to see the close-up view of what they’re working on. With our system, we can present that in a VR environment, rotate or move it anywhere, and scale it as much as we want without confining the surgeon to one perspective like a microscope does. Now, what if you took that a step further and fused our high-resolution light-field data with other existing data in the operating room like CT scans, X-rays, and MRIs? In addition to the camera array’s point of view, you can see what’s going on underneath the surface. By fusing our light-field data with other visual data points that surgeons currently can’t fully leverage, we are opening up a wide variety of possibilities for surgeons to perform surgery in real time and reducing the need for some of the big clunky visualization tools as well as long-term exposure to X-ray radiation in the operating room.

DL: Tell us about your design strategy. What do you need to know about users, and what you have learned from them so far?

EP: There’s a ton to learn about surgeons and their staff, and there’s a ton to learn about the operating room as it exists today.

What I do encompasses everything from building the vision of what an operating room could be, to ethnographic observation—sitting with practitioners and watching how they’re actually treating patients today. We’re trying to understand what occupies their mental and physical space. How much time are they spending getting around their tools versus actually interpreting data and making a detailed treatment plan? Surgery today is full of workarounds. We’re trying to solve the core problems and deliver a dramatically better experience.

Our goal is to minimize the time they spend wrestling with their tools and maximize their time spent focused on the patient. We don’t want a surgeon to have to think about how to work around a particular tool’s shortcomings, or how to focus on information that’s confined to a screen across the room from the surgical bed. We want to make sure they can use their headspace for the right thing, which is to figure how to heal the patient.

DL: In your experience, how are product and UX design evolving with these new technologies coming onto the market?

EP: There’s this idea that as technology becomes increasingly pervasive, we’re going to reach a crossroads, right? I think we’re at that crossroads now. For example, our mobile devices are always with us and they are increasingly context-aware. Yet it turns out that access to more and more data just means more and more distraction in our daily lives. Walk into a mall or anywhere people typically congregate, and half of them are focused on their devices instead of engaging with their environment. It’s unproductive, and more than that, it’s unsafe. What I call “calm design” or “calm technology” is about pushing information into the periphery until it’s needed.

DL: It’s about keeping the human front and center, right? The idea of being bombarded by information is scary to people.

EP: Here’s one of my favorite examples of calm design: Imagine 5-10 years into the future, and you’re wearing a set of augmented-reality glasses pretty much all the time. You go into the bathroom, and the computer vision in your AR glasses picks up that you’re low on mouthwash. It doesn’t immediately notify you that you’re low on mouthwash, because what are you going to do about it during your visit to the bathroom? That’s a useless distraction. Instead, it just makes a note of it, and the next time you’re at the grocery store, it reminds you that you were running low on mouthwash. It might also mention that there’s a sale on the brand of mouthwash you like. That’s calm—it puts information in the background until it’s relevant to you.

Calm design is the key to unlocking the next generation of the operating room. There’s no shortage of companies adding more technology and data into the operating room. The more we put in, the greater the potential to overwhelm the surgeon to the point that they are ignoring half of the information, because they perceive it will slow them down rather than help them. What you want is a system that takes in all this visual information and smartly displays it to you based on when it’s most relevant. So if the surgeon is looking at the patient, they probably want patient-relevant data. If they’re spending a lot of time looking at their hand tool, it might be that the tool is faulty and they’re looking for diagnostic information about the tool. So that’s how we’re thinking of UX design. When can I actually be useful? When should I be in the forefront, and when should I get out of the way? It’s very important that our system is able to do both intelligently.

DL: What advice would you give emerging designers today?

EP: Think about how you would want to interact with information in the future and what would make you want to turn it off. If we can design across the spectrum from low user engagement to high user engagement, we can create tools that help us when we’re not even really thinking about the fact that we might need help, or that can transform the way we interact with other people.

If you could have 19 people speaking 19 different languages all in the same room and still be able to hold a conversation with each other, to me that’s the direction we should be headed. It shouldn’t be a bunch of screens on the wall, or all these apps that you constantly have to load up. It’s about bringing people what they need in the most minimal way possible.

I’d also want to encourage people to start to work outside of their traditional industries. There are leaps that need to happen in VR for it to transform, and I can’t even begin to know or imagine what all of those are. But once they happen, we will suddenly go from “Oh, that’s neat” to a feature or a tool that everyone needs. This is definitely the time for interdisciplinary research and for people coming in from all walks of life to think about what this technology means for them. That’s usually where I get my best ideas—by talking to people from many different backgrounds.

DL: What is the most important thing you’ve learned on this whole journey?

EP: Coming to work and enjoying what I do is vital to me being successful in my job. It’s important to find a research question that motivates and excites you. I’m in a space now where game design is secondary to what I’m doing, which is enabling and empowering surgeons. But a lot of those same research questions that excited me in the game space translated really nicely into this space. People say “Do what you love, and you will never work a day in your life.” I prefer, “Do what you love, and you will work harder and more passionately than you’ve ever worked before.” That’s what inspires me to want to continue to break boundaries, pioneer, and just have a blast doing it.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.