You used to need a new smartphone every year or two. It’s hard to remember now, but upgrading to a new generation of phone once meant gaining access to crucial features: The internet became browsable, photos became legible, and PDFs became openable. There was a time, not so long ago, when you could see the individual pixels on the screen! Imagine that!

But even the smallest remaining pain points and inconveniences left in smartphones have since been sanded away by incremental progress. The smartphone is good now. Sure, it would be nice if they shattered less and the battery lasted longer, but what we’ve had has been fine for some time. No company needs to make a new smartphone every year. That includes Apple and Google, two companies releasing new phones where the camera is the only major upgrade to speak of.

“Frankly, it’s surprising, both Apple and Google haven’t done anything significant here,” says Gadi Amit, founder of Silicon Valley mainstay design firm NewDealDesign, of the forthcoming phones. “They’re still dealing with yesterday’s cycle of spec fight: the camera.”

These days, new features tend to come from software and apps, not hardware. But you don’t need an iPhone 11 to see the latest Snap filter. Meanwhile, the production of new phones takes a staggering environmental toll on the planet. What’s more, consumers seem to care less and less about having a “new” phone. Smartphone sales are already declining globally, and people are upgrading their phones less often—for most of us, a new phone is a deeply expendable purchase.

But is there any alternative to the endless cycle of phone launches? What if Apple didn’t release the iPhone 11? And Google didn’t release the Pixel 4?

For users, life would go on. But for the companies themselves, challenging the cadence of annual releases would be a major risk. “Nobody wants to rock the boat. Nobody wants a faux pas like Samsung, with its [delayed] folding screen,” says Amit. “But it’s kind of a risky proposition. If you continue like that, another year you might find yourself behind.”

A lesson from the car industry

Amit has worked on several secretive smartphone projects himself, including one ambitious attempt to change the way consumers buy phones: Google’s own Project Ara. Ara was a modular phone; the idea was you could upgrade it piecemeal over time, swapping out the processor, or the camera, or any number of sensors, kind of like swapping pieces on a puzzle that could look super gnarly.

In theory, a modular phone would be better for consumers, who could easily replace components to keep their phone working and up-to-date. And it would be better for the environment, because fewer new phones would be made every year. But crucially, Ara also seemed feasible from a business perspective.

“When we worked on the Ara phone, one amazing stat [we came across] was, I think, a third of the profit in the car industry comes from upgrades and options. So the notion of modularity was not benevolent. It’s also the frivolity of upgrades and accessories. You may buy the base phone cheaper, but then you spend $150 on a fancy camera you’re not sure you need. And this is really a lot of profit,” says Amit. “That’s what’s happening with cars. You walk into a dealership to buy the low-cost Toyota . . . then you spend $5,000 on top of that.”

However, the modular phone proved tricky enough to manufacture and uncertain enough to market that Ara was ultimately put on ice in 2016. Notably, Motorola has had some success with a semi-modular phone platform, called the Motorola Z, in Mexico and Brazil, where lower-cost smartphones are popular. But its scope is far more conservative than the vision of Ara.

The smartphone as a subscription?

Is there another way companies could develop a business model that would relieve some of the pressure to sell consumers a new phone every year or two? When I pose the question to Frank Gillett, VP and principal at the analyst firm Forrester, he suggests that another approach is in order. “If you think about [the phone] as access to our digital selves, then that starts to feel like a service,” he says.

What Gillett suggests is that rather than buying a new iPhone or Pixel, you could enter a (hefty!) monthly contract with your phone provider. And for one cost, maybe $100-$200 a month, you get a phone with warranty, voice and data service, bundled apps, and plenty of storage for your photos, videos, and contacts. Then you could pay more or less depending on the phone you wanted (maybe a good, better, best option).

Frank Gillett points to Amazon, which has sort of backed into this model with Prime by offering so many services under one umbrella—and selling highly subsidized hardware to power it.

But selling consumers a smartphone subscription instead of a new phone seems like it could lead to lousy deals for consumers—a glorified rent-to-own scenario. And furthermore, for smartphone makers, the subscription model may not be financially attractive. A subscription might supply steady revenue, but not necessarily a lot of profit at the end of the day. “You sell an iPhone 10 for $1,000, there’s already $400-$500 in profit there [or more]. It’s very difficult to get to $400-$500 in subscriptions,” says Amit, who points out that subscription apps for music, which split profits with third parties, probably don’t offer Apple the margins that hardware does.

And truthfully, Apple (and to some extent Google) has already squeezed this extra service and subscription revenue out of its users already! Apple has iCloud, a new app subscription, its entire App Store for which it takes 30% of revenue, a freakin’ credit card, and warranty options—plus it’s making money selling cases and replacing batteries and glass screens.

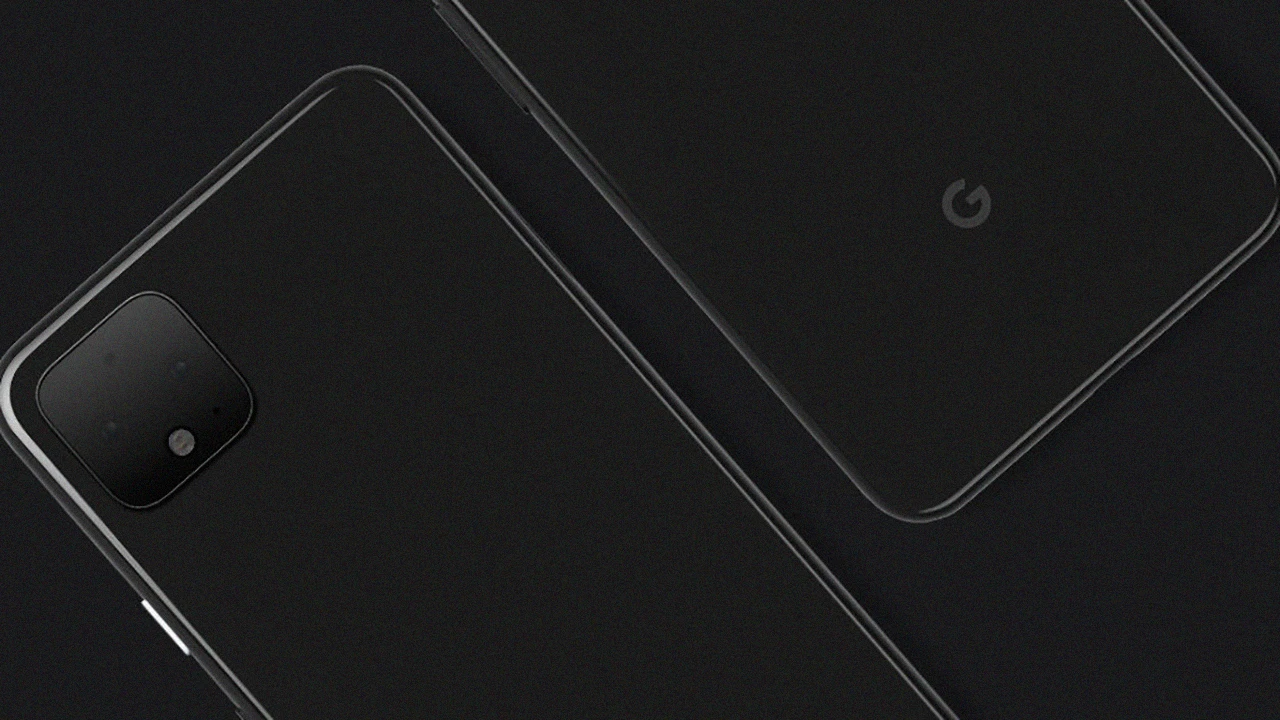

Despite the lack of an obvious alternative to the yearly upgrade cycle, a reckoning is coming to the smartphone industry. I’d argue that Google and Apple know it. Apple recently released the iPhone 11 starting at $700—which was notably $50 cheaper than the comparably positioned iPhone XR cost when it hit last year. Google will reportedly announce its heavily leaked Pixel 4 tomorrow, but the company is also quietly developing some electronics to last for the long-term. You see this most prevalently in its Home projects, like the Home Mini assistant. Google’s design team emphasizes forms and colorways that don’t clash, or supersede, the old generation of Home assistants.

But when it comes to smartphones, it appears that neither Apple, Google, or any of their competitors are slowing down—or passing up the chance to one-up a competitor, even in the smallest of ways.

“You have lack of innovation on one end, and a phenomenon of people being more environmentally conscious, asking questions about it [on the other],” says Amit. “I don’t think it’s sustainable. But currently, nobody wants to admit it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.