I’m sitting in the middle of a Live Nation mixing studio in Hollywood, surrounded by speakers—some low against the wall, some perched higher up. When a live version of Jesse McCartney’s “Soul” comes on, I can hear the booming drums in front of me, crowd noise behind me, and electric piano off to my right. A guitar starts playing behind me and then begins circling above my head. The experience reminds me of the surround-sound immersion of a live concert.

In reality, I’m hearing a recording of McCartney’s song that has been programmed so that I hear specific sounds within the music from different places around my head—a new form of music mixing that Sony calls 360 Reality Audio (360RA). I’m a seasoned musician with four records under my belt, but this kind of music production is totally new to me. Sony hopes 360 Reality Audio will revolutionize the way we listen to music, a change as transformative as the company’s Walkman portable cassette players in the 1980s.

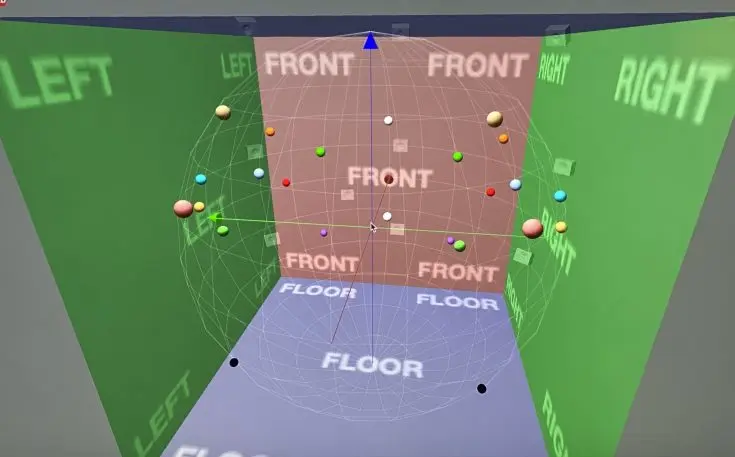

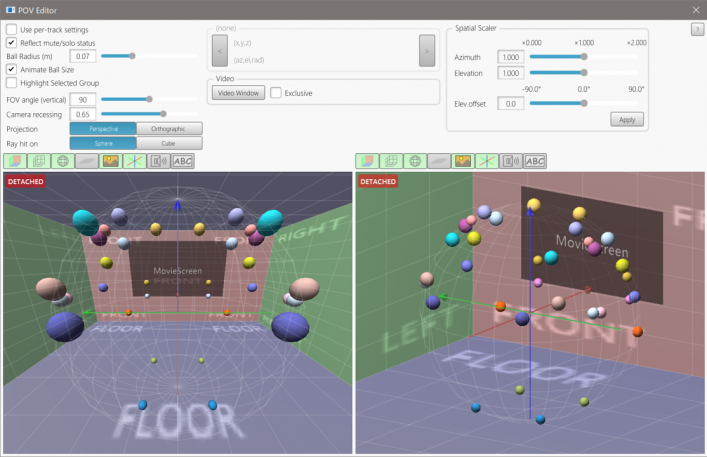

If Walkman used the magic of stereo, where sounds are placed along a left-right axis, Sony’s 360RA is an attempt to more closely replicate real world audio experiences where sound comes from all around your ears. A Sony software program called “Architect” uses complicated audio processing algorithms to place specific sound sources, like a voice or a saxophone, at specific locations within a sphere that surrounds the listener. Using the 360-degree approach for live music in particular makes sense because the goal is to recreate a concert experience, not so much to capture the soul of a piece of music.

While it might not be the revolution that the Walkman was, Sony’s 360RA provides a compelling alternative for listening to live recordings, some of which are now available through the streaming services Tidal, Deezer, and nugs.net.

From surround sound to headphones

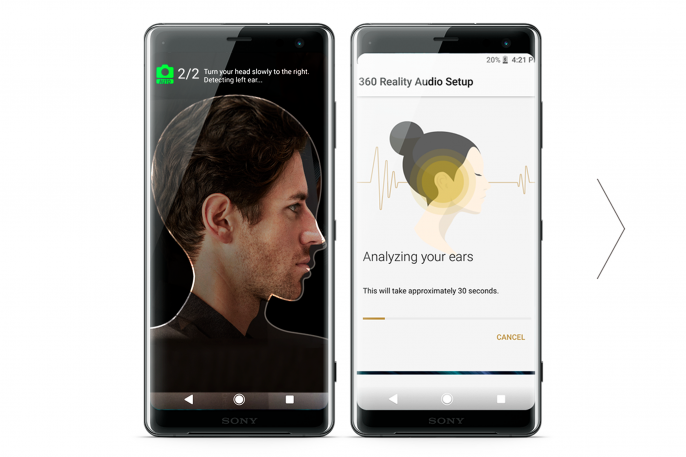

Unlike my first encounter at the Live Nation mixing studio, most people will experience 360RA through headphones. To effectively recreate the 360RA effect in headphones, the audio software needs data about the user’s ears.

But before I could demo the headphone version of 360RA, I had to have my hearing analyzed. Two Sony executives very carefully placed tiny microphones inside my ears to capture what I was hearing. They instructed me to put the headphones on over my ears, and I heard some test bleeps. A software program analyzed what the tiny microphones heard, and that data was used to tell the 360RA software how to model the surround sound in the optimal way for my ears. The more data the technology has, the better it can model the 360RA effect.

Mike Fasulo, SonyI felt like I was right on stage sitting somewhere between the vocals and drums.”

Beyond headphones, audio equipment makers can license the 360RA technology so that people can experience 360RA music on more devices, including home speakers such as Amazon’s new Studio speaker. But it’s not just audio devices that need to be adjusted so that people can listen to music using 360RA. More than a thousand live and studio recordings have already been put through Sony’s Architect software to have their sounds picked apart and placed in different parts of 360RA’s audio sphere. I found the selection of 360RA music on Tidal, Deezer, and nugs.net to be extensive enough to find something I liked, from live tracks to studio recordings that range from Miles Davis to A$AP Ferg to Santana.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EUjZKtZhMpY

But 360RA might be best suited to recordings of live music. Recognizing this, Sony has contracted with Live Nation to go out and record live music performances to put into the 360RA format. To create these recordings, the Live Nation engineers use inputs from the discrete channels of the mixing board. For instance, they might define the signal coming from the microphone directly in front of a horn player as one discrete sound source. Once they have this input, they can use the Architect software to locate the sound of that horn at a specific place within the sphere of the listener’s hearing.

To increase the potential for 360A, Live Nation’s engineers also set up microphones in the back of concert venues so that even the sound back there—including the sound from the PA system and the ambient noise from the room—can be captured and placed at the back of the sphere in 360RA.

I’m not likely to go out and buy 13 speakers to recreate it at home.

So while Sony’s surround-sound speaker experience was pretty convincing—it reminded me of the audio you hear in movie theaters—I’m not likely to go out and buy 13 speakers to recreate it at home. I’m more likely to listen to 360RA with headphones, but the experience doing so really varies depending on how accurately Sony can examine your ear shape. The best headphone experience by far was using the nice Sony cans right after I had my hearing analyzed. Using the Sony app to match my ears with somebody else’s profile was a significant loss in clarity when it came to sound placement. And the least convincing was when I streamed some of the 360RA tracks to my Bose cans with no tuning at all.

The limits of 360 degrees

Sony’s conception of busting out of the limited left-right dimensionality of stereo sound is appealing, but I’m not convinced that 360RA—especially in its more diluted forms—offers something better than what we already have. Sony’s technology is not so much a new way of mixing sound as it is a way of separating it and placing the parts within a sphere, a technique that can effectively emulate live music but may not always be suited to other kinds of recordings.

Sony’s technology is not so much a new way of mixing sound as it is a way of separating it.

In contrast to carefully mixed studio recordings, where every sound is shaped and fitted to create a complete and pleasing whole, the 360RA treatments of studio recordings I’ve heard sound picked apart and deconstructed—not in a pleasing way. Parts sound divorced from the mix for no apparent creative reason. Without the aural experience of a cohesive mix, it feels a bit like a novelty—certainly not something that’s going to revolutionize music production. Spherical effects could eventually be used as a mixing tool that isolates a specific sound at a strategic point in the song. But this kind of effect risks becoming a distraction.

However, 360RA’s focus on isolating and locating sounds may work with some genres of music, particularly jazz. The 360 approach could be used to deconstruct and reconstruct classic jazz music recordings, especially since many recordings from masters such as Coltrane, Monk, and Parker sound like live recordings anyway. In addition, jazz doesn’t always depend on the cumulative effect of musicians playing together in the way that other genres do. Jazz players are virtuosic: You can enjoy the sections of the music that are played in unison, but it’s also easy to focus on the individual artistry of the players—which 360 sound helps emphasize.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyQYtXlSWog

But in other kinds of music, individual instruments often aren’t the focus. The thrill of the music comes from the cumulative effect of instruments playing together—the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. It’s the force of the woodwinds, brass, and strings that gives emotional thrust to the epic crescendo that connects the third and fourth movements of Beethoven’s Fifth. It’s the collective blast of all four Ramones on the End of the Century LP—all their instruments and Joey’s voice melding and swelling into the “Wall of Sound” for which the producer of the record, Phil Spector, was famous.

360RA may not provide the transformative way of engaging with music that Sony is hoping for. But for live music lovers and jazz fans, it could add a whole new dimension to the listening experience.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.