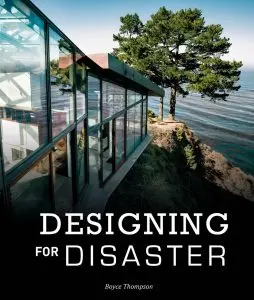

Remember Hurricane Michael? The deadly storm is still fresh in the memory of people on the Gulf Coast. But as author Boyce Thompson says in the introduction of his new book, Designing for Disaster, “in the United States, 100-year storms occur so frequently that people forget their names.”

“We wanted to build it for the big one,” Lackey told the New York Times last year. “We just never knew we’d find the big one so fast.”

While it was an unusual story, that kind of thinking is becoming more common amongst clients commissioning homes in disaster-prone areas. Thompson’s new tome is focused on this emerging genre of luxury architecture, which makes resilience a key amenity.

“Why not spend a little bit to design a house that’s going to last for generations?” as Thompson put it in a recent interview. “That used to be the goal, right? You buy a beautiful house, it would stay in the family for generations. But now with the threat of 100-year storms occurring more frequently than ever, you have to take extra precautions.”

In fact, some argue it’s time to get rid of the idea of “100-year storms” completely. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, a home that sits in a “100-year storm” floodplain actually has a 26% chance of being flooded within 30 years. However, the adoption of more stringent building codes has been slow, in part because industry groups tend to fight any policy that could make construction more expensive. While some architecture firms are beginning to specialize in particular aspects of resilience, like flooding, Thomspon says it was usually the clients who requested the specialized engineering features.

“[F]or the most part, it’s the Wild West,” he says. “The homeowners kind of figure out, on their own, what really matters.”

Many of these single-family homes reflect the cognitive dissonance of the slow-motion crisis enveloping the planet: They are both glassy pieces of architectural indulgence, and carefully engineered, bunker-like pieces of precision infrastructure.

In the most compelling cases, the engineering helps articulate the architectural character: Take architect Bruce Beinfield‘s fascinating home on the coast of Connecticut. The building has a long, narrow, vernacular New England look to it at first glance—but each of its architectural features correspond to an engineering choice. Salvaged wood offers lateral bracing against gale-force winds. Large windows are framed by roll-down steel shutters. Flood vents and piers allow the building to flood without being seriously damaged.

Thompson devotes chapters on homes designed to survive flooding, wildfires, or mud slides, and more generally, extended power outages. But he also trains his eye on projects meant to withstand natural disasters that have been around since time immemorial, like a home designed to withstand a tsunami on the Washington coastline, for instance. These clients clearly know the risks of living on coastlines or in fire zones, and are willing to pay for measures that protect themselves and their real estate.

Research shows that it will be increasingly difficult to find locations in America that aren’t in the path of devastating climate change-related disasters. Yet the homes featured represent a vanishingly small segment of the real estate market; the number of homeowners who can afford to commission their own homes—much less pay for innovative resilience features—is tiny. The AIA estimates that just 2% of all homes in the U.S. are designed by architects at all (for context, some 1.2 million homes were finished in the U.S. in August alone). The number of those that are focused on resilience is even smaller.

Thompson thinks the innovations will eventually trickle down. Much will depend on communities establishing stronger building codes. Moore, Oklahoma, is a telling example: In 2014, the town adopted a new tornado code that borrows engineering technology commonly found in coastal zones, like “hurricane clips” that attach the roof to the walls, and new rafter-spacing guidelines. As Thompson reports, the new code only adds $1.50 or $2.00 per square foot in costs. “Even so,” he concludes, “few jurisdictions in Tornado Alley have followed Moore’s lead.”

The U.S. is desperately in need of more housing units, and of renovation programs to make existing housing more resilient. As Designing for Disaster helps underline, the problem isn’t technological—it’s systemic.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.