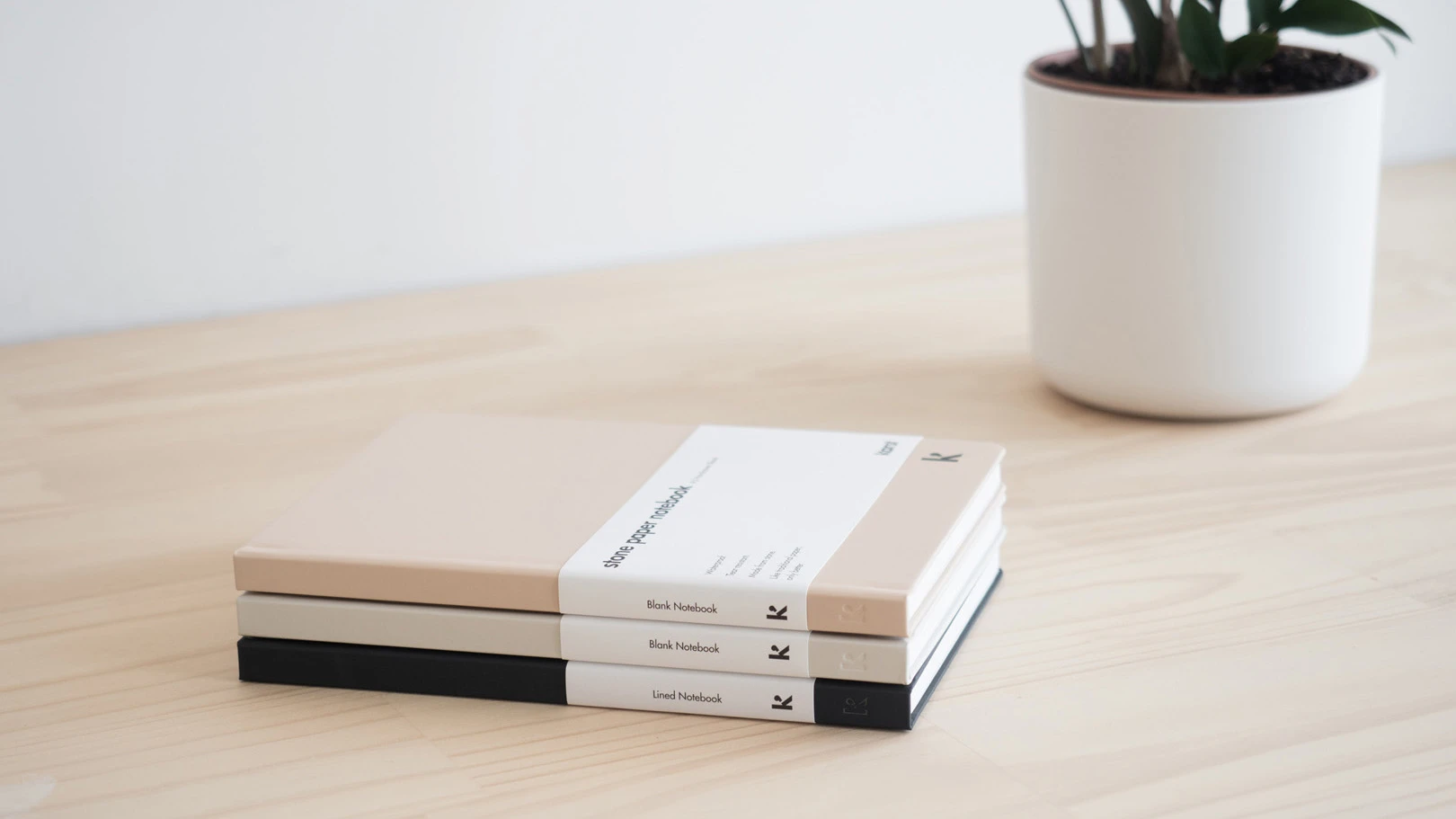

On the surface, Karst notebooks look like those of any other luxury paper brand with colorful covers and smooth white pages. But while the $90.6 billion worldwide stationery industry relies largely on wood pulp, the Sydney-based startup creates notebooks that aren’t made from trees. Instead, they’re made largely from stones that are mixed with a small quantity of resin, a type of plastic.

The hardcover notebooks, which cost $24.95 each, feel much like ones you might get from a competing brand, like Moleskine or Baron Fig, but the pages are also waterproof and tear-resistant. They are also fully recyclable, biodegradable, and carbon neutral, manufactured through a process in which stone—otherwise known as calcium carbonate—is ground up. In this state, stone is actually a very malleable and versatile material. It is commonly used in toothpaste, makeup, and pharmaceuticals.

Karst’s founders, Jon Tse and Kevin Garcia, first came across the idea of stone paper back in 2016, on a vacation to Taiwan. A Taiwanese factory had originally set out to create paper made out of stone for food packaging because the material had all the functionality of regular wood pulp paper, but it also happened to be waterproof.

Three years ago, stone paper was completely new—and the factory was using it largely for industrial products. There were certainly no consumer paper products made from stone. It dawned on Tse and Garcia that stone paper could serve as an alternative to traditional wood pulp paper. “It quickly dawned on us that we should be the ones who could trail blaze,” Tse says.

Many industries rely on wood to make everything from furniture to toilet paper to cardboard boxes. The problem is that trees take decades to mature, which means that when you fell a tree, you cannot quickly replace it. Most American paper products come from Canadian forests. Between 1996 and 2015, more than 28 million acres of these forests were logged, an area the size of Ohio. More than 90% of this logging was done by clearcutting, which removes nearly all the trees from the area. It will take more than a century for this land to return to its pre-logging condition.

Canadian forests contain at least 12% of the world’s carbon in its plants and soils, removing the greenhouse gas equivalent of 24 million passenger vehicles. But as we tear down these trees, less and less of this carbon dioxide is getting pulled out of the atmosphere.

The Natural Defense Council recently issued a report saying that tissue companies—which make toilet paper, paper towels, and tissue—are driving the degradation of forests around the world. The paper industry also has a role to play in this destruction. Even though humans are increasingly more digitally focused, McKinsey found that the paper products industry is still growing at a rate of 1% per year.

The Environmental Protection Agency says that paper and paperboard were recycled at a rate of about 63% in 2013, which is the most recent data. The material degrades with every round of recycling, which is why many companies don’t choose to use recycled paper. In 2011, for instance, only 37% of fiber used to make new paper products in the United States came from recycled sources. And often, manufacturers mix recycled paper with new wood pulp to increase the quality of the finished product.

[Photo: courtesy Karst]

Given how new the concept of stone paper is, Tse and Garcia realized that they needed to create products that looked and felt identical to existing paper products in the market. “[W]e know that in order to make people want to try stone paper, we had to make the products beautiful,” Tse says.

To make the stone paper, Karst sources ground-up stone from construction and mining waste close to the Taiwanese factory, rather than digging up new stone from the earth. They then mix this stone powder with nontoxic resin, and apply heat and pressure to flatten the substance out. After many rotations on large and heavy rollers, the material is thin enough to be used as paper. It is then cut and bound into the notebooks, which looks and feels identical to any other premium notebook on the market.

[Photo: courtesy Karst]

To cut down on waste even further, the factory happens to have a stone paper recycling facility in house. As a result, it is able to recycle scraps or damaged batches of paper in house. This has earned Karst a Cradle to Cradle certification, which validates a company’s sustainability throughout the life cycle of the product. The factory is also powered largely by solar energy, which means the manufacturing operation has 67% fewer carbon emissions compared to a traditional paper operation. And to make the notebooks entirely carbon neutral, Karst plants a tree for every product sold and also partners with an organization called Carbon Neutral to invest in emission reduction projects.

Since the paper is only made of stone and resin, when enough heat is applied the paper degrades back into stone powder and the resin melts. In an ideal world, the notebooks would go back to the Taiwanese factory to turn them back into paper. “This would provide an almost perfect circular system,” Garcia explains.

Karst doesn’t currently have the infrastructure to collect customer’s old notebooks and send them back to the factory to be recycled; this is something the company hopes to do in the future. For now, the founders urge customers to put the notebooks in the plastics recycling stream where they will be burned, separating the powdered stone from the resin. If it ends up in the trash can, the stone in the paper is also photodegradable, which means it breaks down with natural sunlight after 6 to 12 months. Garcia says that the resin fully oxidizes into nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide, leaving no microplastics or halogens behind. The notebooks are also fully compostable if there is enough heat present.

Over the last two years, the founders have developed a customer base willing to try out Karst’s stationery—but now, they’re setting their sights on creating other paper products. Next on their agenda: mailers and packaging.

For Karst, stone paper is not just sustainable, it is a massive business opportunity, given that the paper products industry generates $90 billion in revenue every year (the Memphis-based company alone, International Paper, generates upward of $20 billion in annual revenue). As consumers become increasingly aware of climate change and the destruction of the planet, Karst’s founders believe that they’re eager to find more sustainable alternatives to the products they use every day.

“The paper space is enormous, with multiple players doing billions of dollars in annual revenue with traditional paper,” Tse says. “The industry may not be sexy, but is is huge.”

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.