The new documentary Anthropocene: The Human Epoch doesn’t waste any time getting to the point: For the first minute of the film, all we see are flames. It’s mesmerizing, in a way, the same way that a fire burning in a hearth on a cold night inevitably draws our gaze. But this blaze is underpinned with a sense of horror: In the last few seconds before the scene cuts, we see that it’s burning something—it’s hard to tell what, but we know it’s important, and we know that it’s something to do with our collective future that we’re ruining.

“Anthropocene,” after all, is the proposed name for a new geological epoch that humanity has created by the changes and destruction we’ve wrought on the planet. “Humans now change the Earth and its systems more than all natural processes combined,” narrates actor Alicia Vikander at the documentary’s beginning. The film, which will be released on September 25 and which was directed by photographer Edward Burtynsky along with Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier—whose work on the same subject inspired the movie—traces the scope of human ambition and its consequences across the globe.

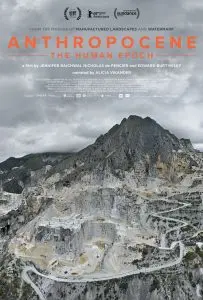

That scope comprises a number of damaging human endeavors: extraction, or the removal of resources from the earth; anthroturbation, or digging tunnels under the landscape; technofossils, or the dumping of human-made products like plastic into the environment; terraforming, or the act of altering the Earth’s surface for human needs. These categories, Baichwal tells Fast Company, were laid out by the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), a cohort of scientists studying this new epoch. To illustrate them, the filmmakers bring us to Nairobi National Park in Kenya, where we see workers sorting through 105 tons of ivory from elephant tusks, and to Norilsk in Siberia, where the world’s largest heavy-metal smelting complex in the world has resulted in the most polluted city in Russia. We see mechanical jaws clamping down on marble deposits in Carrara, Italy, and trees felled on Vancouver Island, where less than 10% of the old-growth forest remains.

While the filmmakers followed WGA scientists to these sites, the experts don’t themselves appear in the film. Baichwal says the filmmakers wanted to avoid the talking heads common in documentaries in favor of a “nondidactic, experiential approach where people are transported to places they would never normally see.” Anthropocene is almost more of an art film: The camera lingers, and narration is sparse. “We often get nailed for not being strident enough in our messaging,” Baichwal says. “But when people can viscerally experience something in their own mind, it’s more powerful than being told what to do.”

Many of these scenes will be familiar to those who have seen Burtynsky’s photography work: A 2018 book, by the same team that made the film, was released as part of a larger multimedia initiative called The Anthropocene Project, featured much of the same imagery. But in the film, we hear directly from the people at each of these sites. In Norilsk, one woman who works at the mine describes knowing her home was not a normal city, “but once you adjust, it pulls you in, and it becomes your own,” she says. “You become a romantic.” Another chimes in saying that you start to see beauty in flowers growing out of the concrete.

While Anthropocene paints a bleak picture, there are moments of optimism and progress: People are figuring out how to grow crops indoors to save resources, and harmful practices like poaching elephants for ivory are being outlawed. While humans have caused the destruction and devastation captured in the film, we are both responsible for and capable of remedying it. “The tenacity and ingenuity that helped us thrive can also help us pull these systems back to a safe place for all life on Earth,” Vikander narrates.

Corrections: We’ve updated this post to reflect that the entire team of Burtynsky, Baichwal and de Pencier worked on the earlier book of photographs and were all inspirational to the movie, as well as correcting the name of the Anthropocene Working Group.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.