There’s a nice piece of fruit in your refrigerator right now. Perhaps it’s a veggie. Or a boneless skinless chicken breast. Whatever it is, you’re definitely going to eat it. You’re not a food waster! But here’s the truth: There’s only a 50% chance, or worse, that you’ll finish any of those things, in their entirety, a week later. The rest will only be partially eaten, or perhaps prepared and sitting in your fridge as leftovers. In any case, much of that remaining 50% will end up in the trash soon, representing lost money and one of the greatest contributors to carbon emissions and climate change.

In the U.S., we waste as much as $218 billion on uneaten food every year when analyzing the entire supply chain, including farming and processing. Globally, the carbon emitted by wasted food can be classified as its own country—the third worst carbon emitter in the world, behind the U.S. and China.

“People put things in refrigerators with the best intentions, while letting them, the majority of time, live slow, miserable deaths,” says Brian Roe, professor at Ohio State University, who has studied matters of food for more than 20 years.

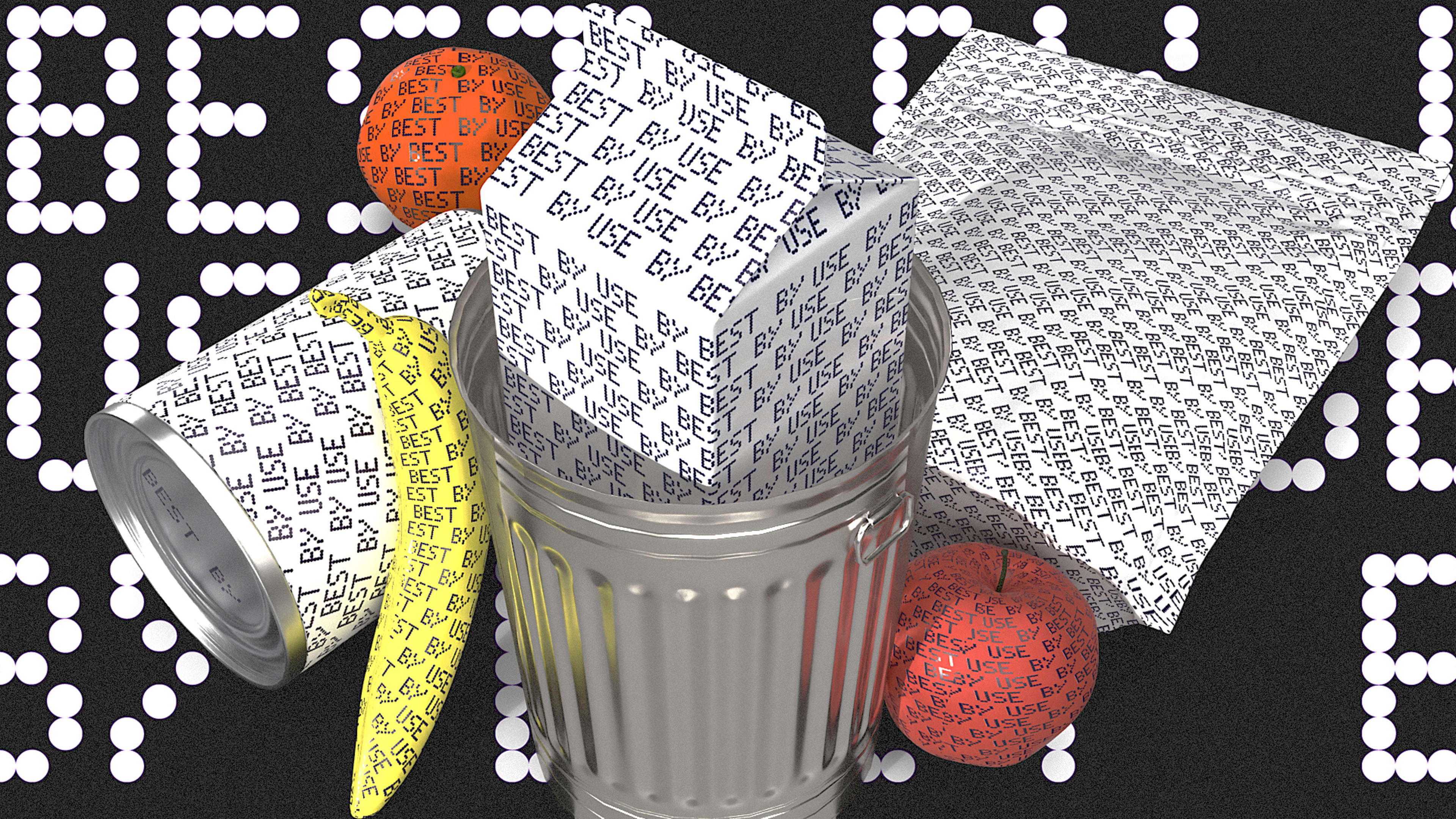

Sometimes things do just rot before we eat them! But often, food is tossed because of a more confounding culprit: the expiration label. According to Roe’s most recent paper, published in Resources, Conservation, & Recycling, those “best by” dates on packages are the third most-common reason we throw away food in our fridge.

The problem with that? Often, those labels are unstandardized, unclear, misleading, and sometimes even wrong, which means edible food goes to waste. Furthermore, an expired food label can also alleviate the guilt of wasting food.

For this study, Roe and his collaborators polled 307 people, asking them all sorts of questions, like how often they shop and clean out their fridge. They also asked subjects to share the contents of their fridges, and then they followed up a week later, asking about randomized items, to get a picture of what had been eaten, and what had not.

As for things not eaten, the team analyzed why. The guilty variable was often the food label itself, and likely the belief that the food had gone bad because it had officially “expired.” Based on their analysis, the catch was that much of that food was still probably perfectly edible. So what went wrong? Food expiration labels are broken, and even the food industry knows it.

As Roe explains, two powerhouse food industry groups, the Food Marketing Institute and Grocery Manufacturers Association, made a joint statement on the issue in 2017. They suggested the adoption of a two-party system of food expiration labeling that could cover all circumstances. The first was “best if used by,” which should indicate that, after a certain date, the food may drop in quality (but still be safe to eat). The second was “use by,” which should indicate a safety issue that could occur after a given date. Such foods are actually few and far between, Roe explains—such a label should generally be necessary only for foods like deli meats and soft cheese.

Legislation to formalize these recommendations as law has been kicking around Congress since 2016. A third iteration of the proposed bill, dubbed The Food Date Labeling Act of 2019, is currently under review at both the House and the Senate. “I don’t think anyone is really against it,” says Roe, who cites some bipartisan support. “I think some of the manufacturing interests are hesitant to allow in regulation of any sort. I think they’d prefer to do it totally voluntarily.”

So for now, we live in kitchen chaos. One yet-to-be-published study from Roe’s group, which documents expiration date alternatives that food producers currently use, offers a look at just how random and difficult these labels are to parse.

“Man, there are so many phrases out there,” he says with a laugh, before pulling up a spreadsheet of his data to read a few off to me. “Let’s see, there’s ‘best before,’ ‘best by.’ ‘Sell by’—that’s probably the most prevalent one. It should actually be used by the retailer to know when to really push product out the door, move it out, or sell it. Then you have other phrases. ‘By.’ ‘For best taste use by.’ ‘Best before.’ Some of the more creative? ‘Guaranteed fresh until.’ ‘Harvested on.’ ‘Enjoy by,’ that’s a good one!”

The problem is that none of us really knows what any of these things mean, or where the line between quality and safety is. If I don’t “enjoy by,” will I “die after”? One common version—simply listing the date with no accompanying text—is actually the worst option of all. Roe’s research found that these vague, date-only labels triggered people not to finish food at a very high rate.

The solution, to Roe, is the two-label system that would be mandated by the proposed law. It’s not that the wording is perfectly clear by any means. (I, for one, had no idea about the premise of enjoyment vs. food safety before reporting this article.) It’s that we just need to agree on something, so that we can all agree upon what that something means.

“In this case, I think there would be a public benefit to having common phases so we could establish a nice educational campaign, so you didn’t have to interpret eight different phrases as meaning the same thing,” says Roe. “I think you could quibble over which phrases are the best for those two purposes! But I think we need to pick two and run with them, and embed into people’s thinking. These things take years, if not decades, to bake into people’s minds.”

Will better labeling truly move the needle on food waste and climate change? Yes. In another unpublished and still unreviewed paper Row is working on, he found that the right phrasing can reduce the intent to throw something away by single-digit percentage points. Not bad for rethinking a bit of ink.

The even greater opportunity, however, is in getting the food industry to consider its own dating standards. Roe doesn’t suggest we consume food that might harbor bad bacteria by any means. He suggests that, if a food company can stand by the quality of its product for just another day or two (meaning the “best if used by” label had a few more days on it), that could decrease intent to toss an item by as much as 20% to 30%, which could make a massive impact on food waste. “But that’s a marketing conundrum,” he admits. “You’re going to put product out there, and there’s a greater chance it will lose the vigor of quality before people consume it . . . so that could [challenge] your quality.”

In the meantime, when making decisions on what to keep and what to toss in your own fridge, Roe urges people to give each item of food its own fighting chance.

“There’s always a strict label date enforcer in every household. They say it’s the law!” he laughs. “Help them take that step. Unless it’s deli meat or soft cheeses, it’s probably not the law. It’s just a suggestion. Use your nose, take a nibble, and give it a second chance before you toss it automatically.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.