The Mac will always be identified with the year 1984. But 40 years ago, the Macintosh project started as an under-the-radar effort within Apple by Jef Raskin—he dropped his first name’s second “f,” deeming it redundant—who was the company’s publications manager and 31st employee. In an era when computers were still largely the province of enthusiasts and geeks, he envisioned a device that was approachable and affordable enough for the masses, and named after his favorite apple—the Macintosh.

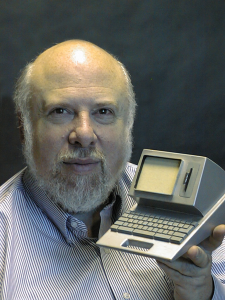

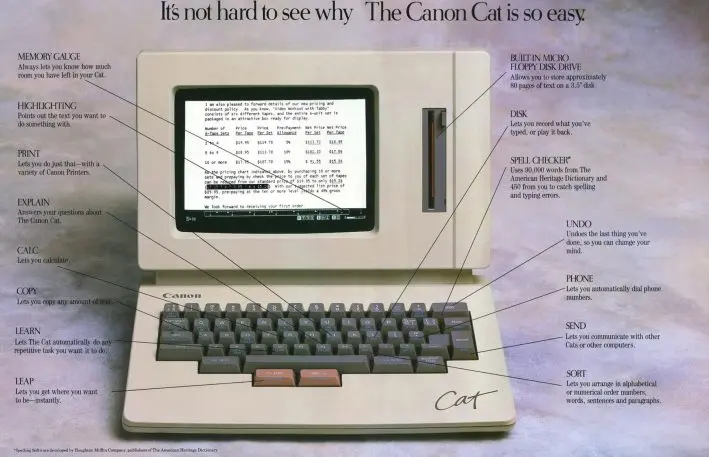

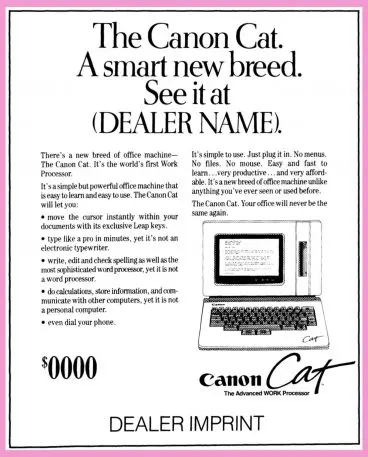

Once the project came into Steve Jobs’s orbit, the Mac that was launched was a considerably different machine than what Raskin had intended. And by then, he had already left Apple. However, he never gave up on producing an “information appliance” that embodied what he called a humane interface. He got his chance in 1987 with the Canon Cat, a $1,495 “work processor” marketed as “the brainchild of the man who originated The Macintosh Computer.” The Cat had a 9-inch monochrome display like the first Mac but with an industrial design straight off the bridge of the original Star Trek’s Enterprise. Within the device lived a user interface focused on getting work done—and even though the Cat was a short-lived disappointment at the time, it remains fascinating in this age of technology-driven distraction.

Within that document, you could create tables with formulas, similar to how you could with later integrated packages such as Microsoft Works or the modern web document processors Quip or Coda. The Cat even allowed you to include computer code in the middle of a document that could be executed with a button press.

A promotional video on YouTube demonstrates the superior efficiency of a typist making corrections in a document using the cursor keys of a command-line interface or the mouse of a graphical interface versus Leap. (The video itself is less than efficient, and includes about seven minutes of a static logo at its end.) However, while the video acknowledges the existence of keyboard-based shortcuts in other word processors, it dismisses them as being hard to memorize compared to Leaping. As a system-wide function, Leap let you quickly navigate to a point in any document on the system, not just the one on the screen.

Innovative though it was, the Cat did not take off. Canon sold only 20,000 units, according to oldcomputers.net, and quickly vanished from the market. Raskin allegedly blamed poor marketing. Other stories suggest a battle between the Cat team and those producing Canon’s traditional word processors, a parallel to the civil war that raged at Apple between the Apple II and Macintosh teams. An even juicier theory stipulates that Steve Jobs, who was at his second computer startup, NeXT, when the Cat debuted, insisted that Canon kill the Cat. (The Japanese electronics giant produced a high-quality, inexpensive laser printer for the NeXT and came on board as an investor in Jobs’s post-Apple venture.)

Raskin continued developing the ideas behind the Cat long after its demise. And after he died in 2005, his son Aza continued them further, developing a launcher for Windows called Enso. Ultimately, the effort was turned over to open source where it failed to find developer support.

Where might the Cat have gone if it had survived? As the Mac and Windows evolved, their apps extended far beyond the word processing and spreadsheets that defined office computing during the Cat’s gestation. Even if Leap had achieved far greater success on the desktop, it likely would have translated poorly into the modern, mobile world. In some ways, the early BlackBerry interface was a spiritual cousin, eschewing a touchscreen and apps and relying heavily on keyboard shortcuts to get things done efficiently. But the far greater popularity of graphical interfaces with inviting icons paved the way for the dominance of the iPhone and Android user interfaces. And would you really need a Leap key to compose a tweet?

Still, the Cat’s overarching aspirations remain intriguing in this age where writers who need to focus on their work for extended periods seek distraction-free composing environments. On one extreme, Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin used WordStar, a keystroke-centric word processor even older than the Cat, on a desktop relic to compose the fantasy novels that drove eight seasons of epic HBO programming. More casual writers would likely prefer something a bit friendlier and more portable. The creators of the Freewrite “smart typewriter” are nearing shipment of a clamshell dubbed the Traveler targeted to these users, but its integrated software doesn’t emphasize rapid document navigation. To the contrary, one of the changes the company begrudgingly added in the new machine is cursor-key navigation—but without dedicated cursor keys.

Alas, one of the projects that never left Raskin’s drawing board was a Cat laptop that weighed about two pounds.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.