Minecraft, one of the most popular games on the planet, is headed for the real world.

In its new augmented reality evolution Minecraft Earth, players can collect resources, build super structures, and meet and battle mobs in a familiar-looking territory: their own neighborhoods. Whereas Pokémon Go enabled you to catch virtual monsters in the real world, Minecraft Earth lets you build entire digital cities on top of the real world (a phenomenon dubbed the Metaverse in old sci-fi). You can do this on your own, and explore the digital creations you add to your own community, or build and navigate structures together with other players. As the lines between the digital world and meatspace blur, Minecraft Earth is a compelling vision of what that new intermediary space might look like.

The app is beginning to roll out in beta out this summer, and Microsoft, which develops Minecraft, aims to reach all 91 million of the classic game’s players eventually. But right now, it’s only available in a closed beta in London and Seattle. I live in the latter, so I gave it a try. I spent the weekend navigating my city in AR, and while the technology is certainly impressive—with the potential to reshape the way gaming happens in the future—it left me with a bigger question: to what end?

Like playing with a toy no one else can see

As I’m sitting on my couch having coffee, I open the app. I see my player standing on what looks like a three-dimensional map of my neighborhood, which Microsoft created using OpenStreetMap. The specifics are gone—all buildings appear as uniform, bright-green structures—but I can see the basic layout. Should I leave my apartment and walk to the right, I’d cross a busy street then reach the canal at the bottom of my neighborhood, and my player would do the same. Scattered throughout are resources, called “tapables,” that I can collect to build up my inventory. Once I get enough materials, I can start to create structures and habitats, called “builds,” in my augmented-reality environment.

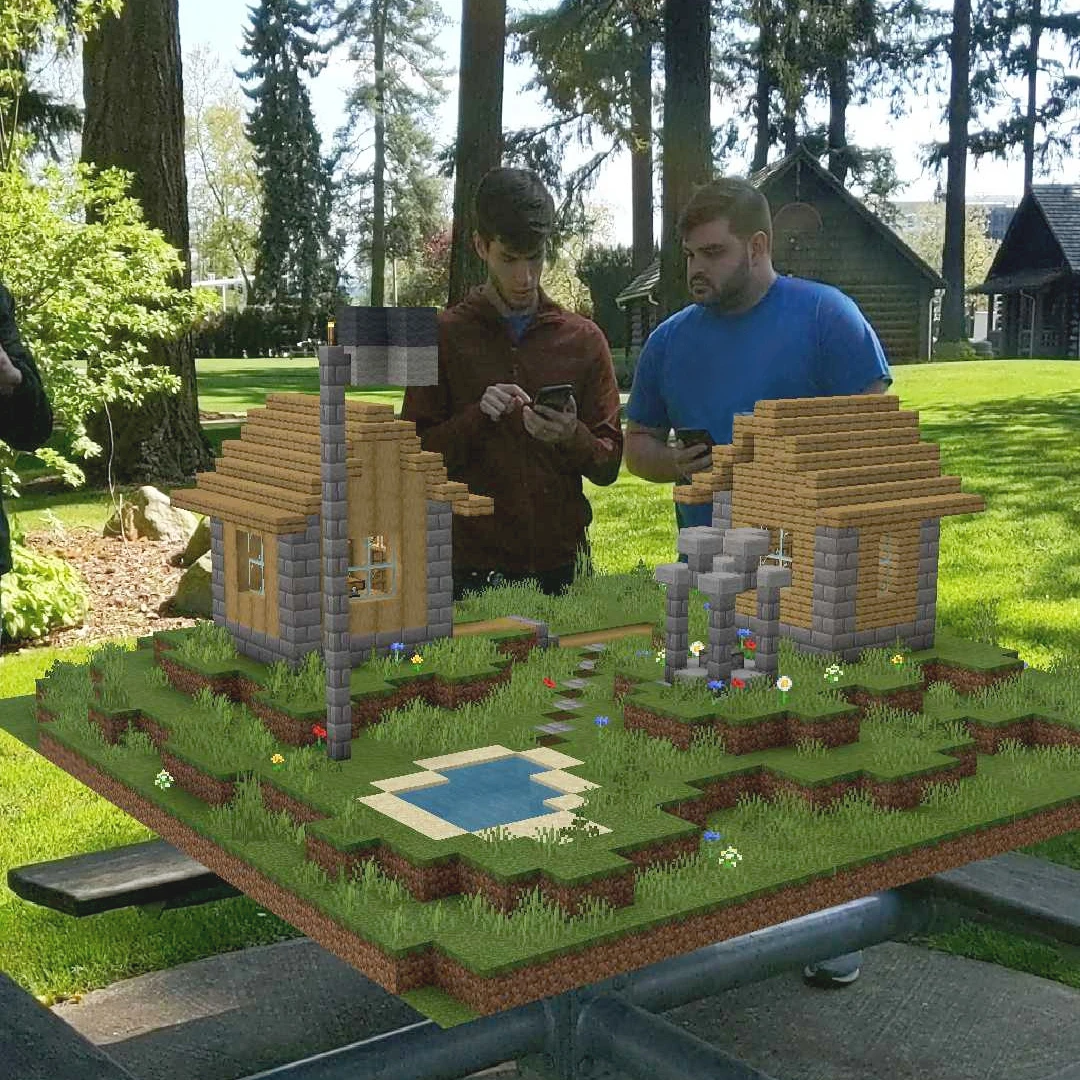

I try doing that later, at a brewery. By then, I had collected enough resources for a basic “build.” Minecraft Earth equips players with templates that they can manipulate, and this one has a tree-like structure in the corner, with a creek running through and grassy blocks lining it. I select that one, and drop it, in the app, on the table where I’m sitting. Now, I’m face to face with this digital environment. With the resources I’ve collected, I build a wooden path alongside the creek, and add some tulips. The whole habitat, on the brewery table, appears slightly taller than a pint of beer. I can rotate it to see it from different angles, and add or subtract elements at will. It’s like playing with a toy nobody else can see.

[Image: courtesy Microsoft]

The bigger promise: building community through gaming

But that’s because I’m the only one in my group with access to the closed beta. Where Minecraft Earth gets really interesting is with its collaboration element, which I did not get to experience because the beta is so limited. Had I been sitting there with people who all had access to Minecraft Earth, we could scan the tabletop with our mobile phone cameras, and co-create the habitat. And if we wanted to, we could decide to move what we’d built to the floor and enlarge it—the app allows players to translate a “build” to another space and resize it. By making the structures human-scale, we could actually step inside and explore the environment we created inside the real-world space. From the perspective of other people in the brewery not in Minecraft Earth, it would just look like we were standing around, pointing our phones at each other. But in the game, we’d be in an entirely new space that we made ourselves.

It’s not difficult to see how the game could transform someone’s experience of a city. In cities, it’s easy to focus on problems—broken streetlights, potholes, vacant lots—and feel a distinct lack of control or agency. Minecraft Earth hands the creative reins to the players, who can turn their neighborhoods into their own personal objects of wonder. Walking around one of Seattle’s parks with Minecraft Earth, you might see treehouse-like structures built among the evergreens, or a holographic fortress among the buildings of downtown.

A way to foster community, but to what end?

The appeal of the game, though, hinges on the premise that the real world exists to be improved upon in ways that, no matter how interactive Minecraft Earth makes them, are ultimately intangible. For groups of friends who want to develop their own in-game layer through which to navigate their city, Minecraft Earth presents an unprecedented community. But for me, the concept didn’t quite land. I found myself distracted and frustrated at having to have my phone out at all times to collect resources when I was trying to walk around and enjoy the first genuinely warm weekend Seattle has had all summer. Without the ability to collaborate with others on my in-brewery habitat, I simply felt antisocial and preoccupied with something only I could see and experience. And it raised a much larger question: Is this the right way to interact with our cities? There are so many Herculean problems in cities, from inequality to unsustainable development. And there’s no doubt that we need a collaborative, community-based approach to addressing them. Minecraft Earth centers on community-building, but does it also give people a way to disengage with the real problems in front of them?

Of course, I can’t speak for everyone. I didn’t get into Pokémon Go either—a game to which Minecraft Earth is already drawing comparisons. In 2016, Pokémon Go sparked a phenomenon as players used the augmented reality platform to collect Pokémon in the real world. More than 800 million people downloaded the game. With its popularity also came some problems: Reports of robberies at the scene of Pokémon-catching sites sprung up as the game took off, and some parents were even arrested on child negligence charges for leaving their kid at home to collect Pokémon on the app. As augmented reality games like Pokémon Go and Minecraft Earth scale up, they could also pose challenges to personal safety and reinforce the need to create firm boundaries between games and real life.

Minecraft Earth is arguably much more advanced than Pokémon Go. What’s unclear is whether the uptake will be as swift. While Pokémon Go simply added the interactive layer of catching Pokémon to players’ experience of navigating their neighborhood, Minecraft Earth wants players to take an active, collaborative role in recreating where they live, which arguably requires more of their time and effort. But the larger value proposition will likely influence gaming for decades. Ultimately, Minecraft Earth breaks down the idea that gaming happens between one person and their computer. Now, it’s something that people can work on and experience together.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.