Until recently, a vacant lot on a street in North Miami held an ordinary single-family home. But after it flooded repeatedly, and as sea-level rise continues to make flooding even more common in the area, the city decided to use a grant to buy the land. The site will soon become a community space that doubles as a place for stormwater management, helping keep other houses on the block dry and creating a model that could be used in other neighborhoods.

“The city of North Miami, like many cities across the United States, is really grappling with this issue of what to do with homes and properties that are repeatedly flooded,” says Kokei Otosi, a project manager at Van Alen Institute, a design nonprofit that partnered with the city on a competition to redesign the lot as part of a larger project to find new solutions for climate resilience in the Miami area. “Dealing with those challenges when people are occupying those spaces means a drain on flood insurance and means rerouting resources from areas of need to restore these homes. . . . So the city is really trying to think proactively about how to prevent those challenges.”

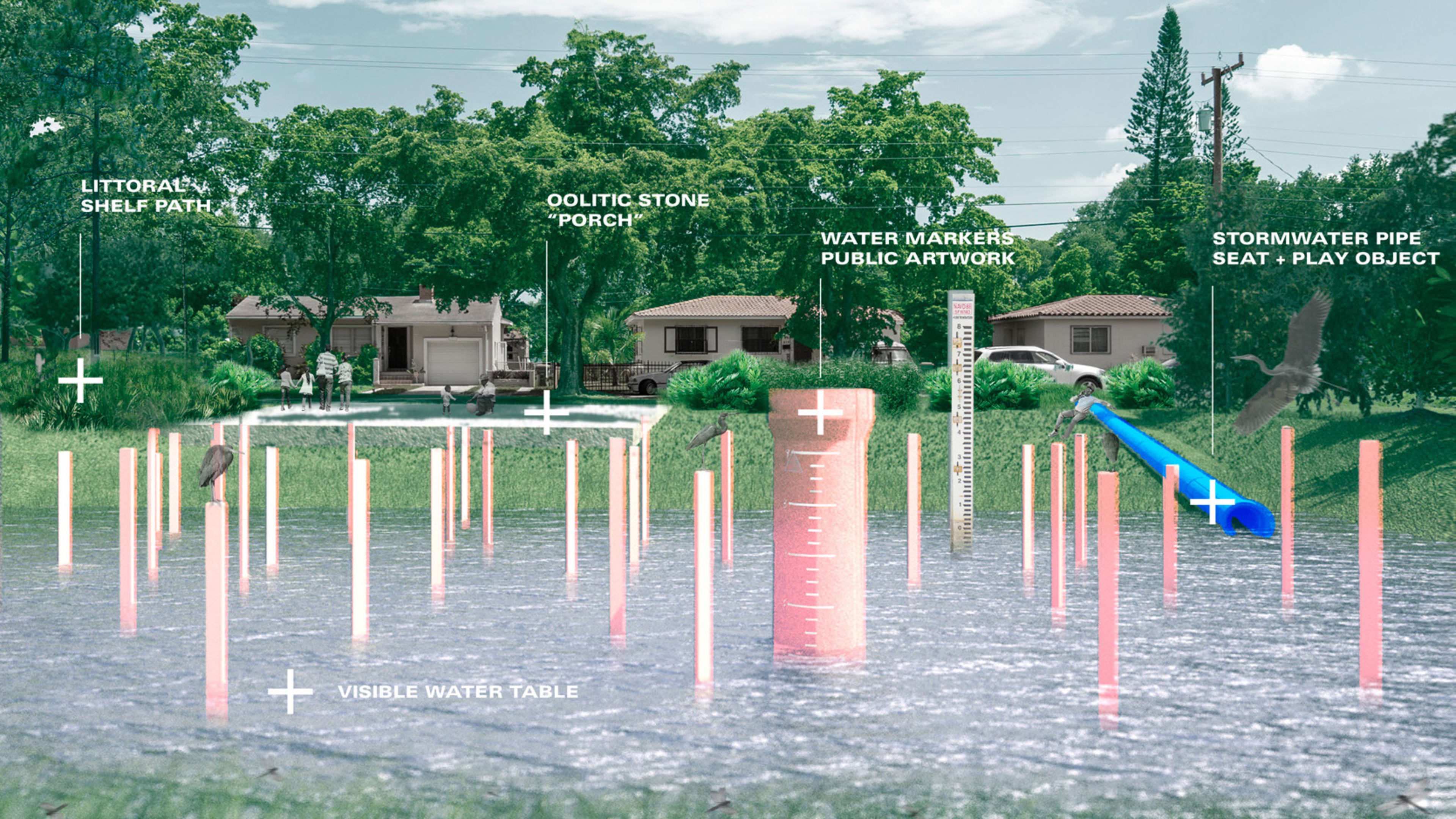

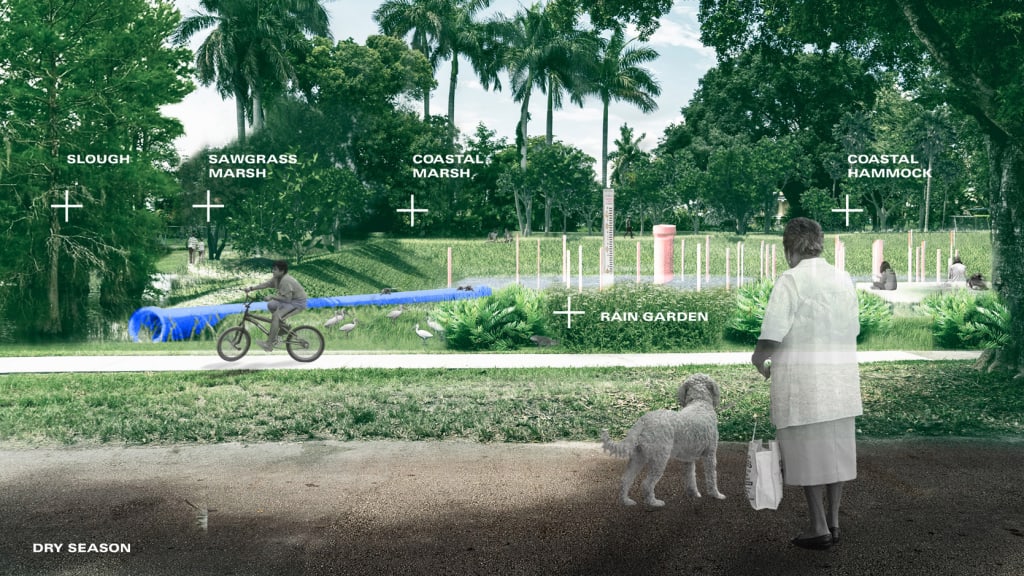

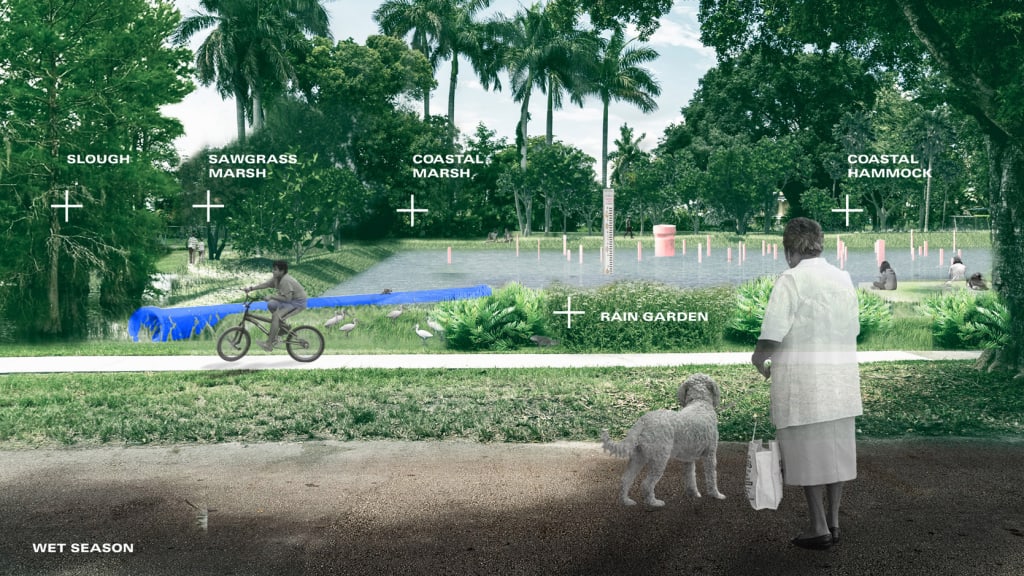

The winning design proposal, called Good Neighbor, includes a retention pool that can hold water that otherwise could flood nearby homes. An art piece in the pool uses physical markers, rising above the water, to show people walking by the current level of flooding. Surrounding the pool, a walking path will be planted with plants and trees from local ecosystems that have been largely lost to development.

“I think that this is an opportunity to create sites that simultaneously reduce risk, provide community gathering places, as well as grow public awareness,” says Maggie Tsang, cofounder of Department Design Office, the design firm that collaborated with artist Adler Guerrier, architect Andrew Aquart, and hazard mitigation startup Forerunner on the winning design. Infrastructure is typically invisible, but being on a residential lot offers “a chance to change that narrative,” she says, “and to really create an opportunity to make things visible and register that change on a day-to-day basis and more broadly grow environmental consciousness.”

In FEMA’s terminology, the lot is called a “repetitive loss property.” But the designers wanted to recast it as something positive. They calculated that the new basin could help reduce flooding at as many as 20 other homes in the area. Similar parks could help in other neighborhoods. “We considered this as a kit of parts that could be applied to a variety of different lot types,” says Tsang. The team will now work with the community on the final design for the pilot project, which will open this December.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.