This is the 49th in an exclusive series of 50 articles, one published each day until July 20, exploring the 50th anniversary of the first-ever Moon landing. You can check out all the 50 Days to the Moon stories here.

NASA almost went to the Moon without packing an American flag.

In fact, at the moment the space agency decided it wanted to take a flag, it was so close to the launch of the first Moon landing, there was a scramble to figure out what kind of flag, how to get it to fly on the airless Moon, and even where to carry it on the spacecraft.

In the 1960s, NASA was legendary for its planning. Every second of every Apollo mission was plotted out—scripted—so that everyone both on the ground and in the spacecraft knew what they were supposed to be doing at every moment. (This remains true: Every spacewalk is rehearsed eight times back on Earth before being tried in space.)

But during Apollo, there was no one in charge of celebrating the Moon landing, no one thinking about a simple moment to mark the human achievement of making it to the Moon. So the idea of taking a flag, of planting a flag, wasn’t on anyone’s to-do list.

The moment that sparked NASA into action was a line in passing from President Richard Nixon’s inaugural address.

With Apollo 8’s historic orbiting of the Moon just three weeks finished, it was clear that the U.S. was quite likely to put astronauts on the Moon in 1969, Nixon’s first year in office. With victory in the race to the Moon clearly in sight, he sounded a generous, inclusive note in his inaugural:

“Those who would be our adversaries, we invite to a peaceful competition (in space)—not in conquering territory or extending dominion, but in enriching the life of man. As we explore the reaches of space, let us go to the new worlds together—not as new worlds to be conquered, but as a new adventure to be shared.”

Three days later, George Low, the legendary Apollo project manager, wrote a revealing, single-page memo to Robert Gilruth, director of the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston.

Low had just gotten a call, he wrote, “indicating that, in light of Nixon’s inaugural address many questions are being raised in Headquarters as to how we might emphasize the international flavor of the Apollo lunar landing. Specifically, it was suggested that we might paint a United Nations flag on the LM descent stage instead of the United States flag. My response cannot be repeated here.”

On the contrary, Low wrote, “I feel very strongly that planting the United States flag on the Moon represents a most important aspect of all of our efforts.”

How to fly a flag where there is no air

With barely six months before the first Moon landing, it was incredibly late in the process to be thinking about this. The equipment that was going to carry the astronauts to the Moon—and the equipment they were going to use on the way and while there—that had all been designed, tested, and manufactured. Plus, the astronauts had been training with it for months or years.

Gilruth, in Houston, quickly created something he called the Committee on Symbolic Activities for the First Lunar Landing to figure out what exactly to do to celebrate that first landing.

The Committee On Moon Celebrations, as we might think of it, appears to have met once: April 1, 1969.

Gilruth had reached out in advance of the meeting to a singular Apollo-era character named Jack Kinzler for ideas. Kinzler had the mundane job title of head of technical services in Houston, running a group of 185 craftsmen and technicians who made special equipment—and solved special problems—for U.S. space missions.

Kinzler was a self-taught engineer who never went to college, and over an almost 40-year career at NASA, he earned the nickname “Mr. Fixit” for his ability to solve sometimes urgent problems on the fly. After watching a Russian cosmonaut flailing around during the first-ever spacewalk in 1965, for instance, Kinzler’s group in Houston created a handheld gadget that used small cylinders of nitrogen to give American astronaut Ed White the ability to use bursts of gas to maneuver in space during the first U.S. spacewalk during Gemini 4 a few months later.

Gilruth asked Kinzler to come to the April 1 meeting with some ideas. He arrived with two: a plaque and a flag on a flagpole that could be planted.

The plaque he and his staff had designed was curved, so it could be mounted around one of the legs of the lunar module, on the part that would stay on the Moon.

Although the module itself had a flag painted on its side, just like almost all U.S. flying craft do, it was almost never even visible in photos from the Moon.

Kinzler thought it was “a terrible way to celebrate” something as momentous as landing on the Moon. He’d come with an idea for a freestanding flag. That’s what explorers did: They planted flags.

Columbus. Lewis and Clark. Roald Amundson at the South Pole. Robert Peary at the North Pole.

The American astronauts weren’t claiming territory—a new U.N. treaty forbade any nation from claiming dominion or control over celestial bodies—but the Apollo astronauts were explorers as ambitious as any that had come before, representing a nation that had invested as much effort as any nation ever had in an expedition.

How could they not raise a flag?

The problem was that an American flag, on a pole, would simply hang limp. The Moon has no atmosphere, nothing to make a flag ripple in the breeze, or even stand out.

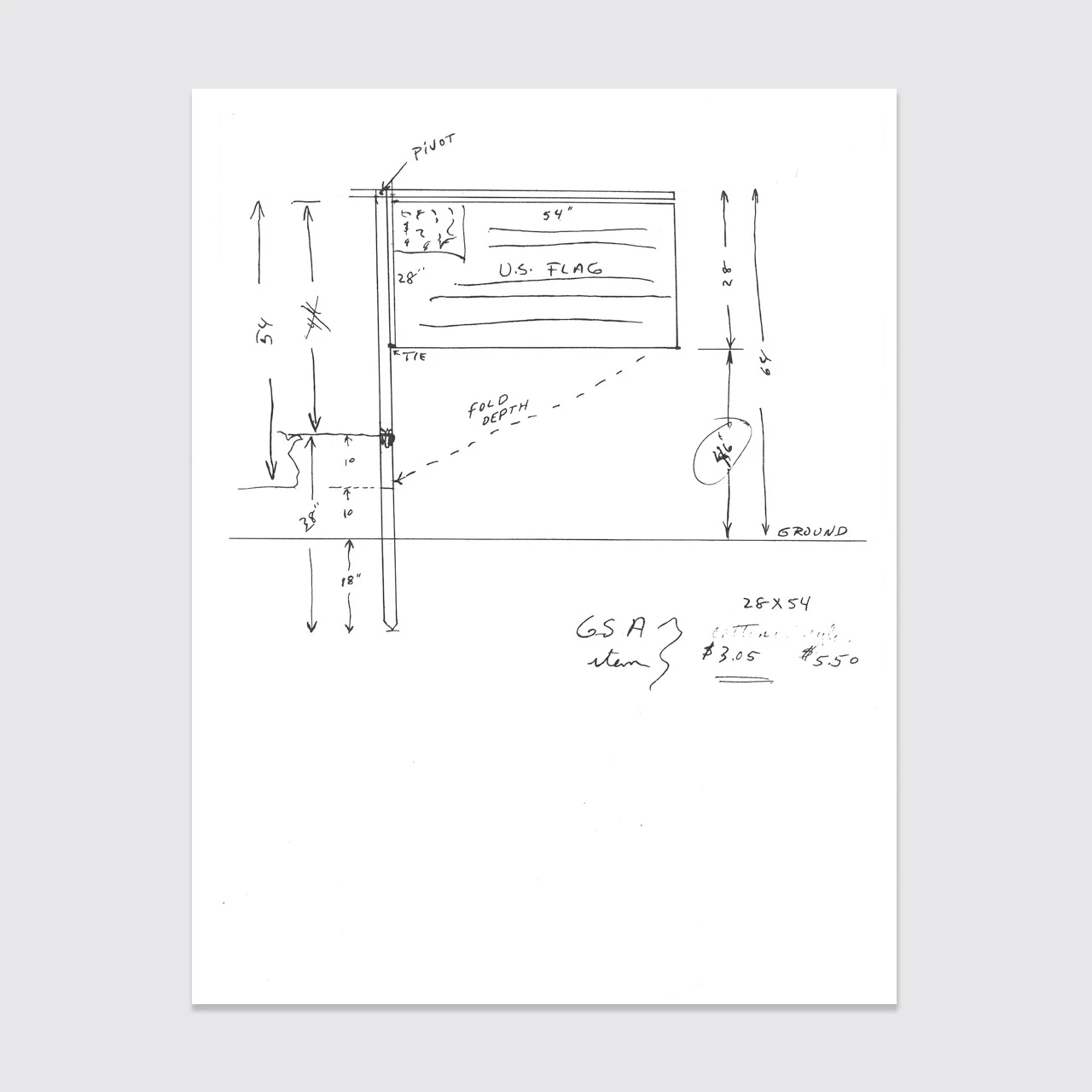

Kinzler had come up with a simple, ingenious solution to that problem.

The flag would have two poles. The classic vertical pole, to hold the flag; then, hinged to that pole, at the top, a second pole which the astronauts would swing up into a horizontal position, where it would latch in place.

The flag would have a hem along its top edge, and it would slide out on the horizontal pole, just like a curtain slides along a curtain rod. Kinzler acknowledged that he was inspired by the curtains his mother had sewn when he was growing up.

The two poles and the flag themselves would fold up into a slim, easily toted package, like a tent fly and poles. The flag could be deployed and erected with minimum effort, but with dramatic effect. Kinzler imagined a flag that was 3 feet tall and 5 feet wide.

As for where to carry the flag, it was far too late to go through the testing and approval process to put it inside the lunar module cabin with the astronauts. So Kinzler hit on the idea of attaching the flag kit to the outside of the lunar module, to one side of the ladder the astronauts would climb down to reach the surface. The flags themselves were off-the-shelf, commercially available, nylon American flags.

Don’t let the American Flag hit the dirt

That first flag had a kind of improvisational feel right up to the end, which is remarkable given how significant it ended up being. Kinzler himself packed it in its protective container with a handful of staffers in his office days before Apollo 11’s July 16, 1969, launch.

Kinzler, the flag, and the commemorative plaque traveled from Houston to the Cape aboard a Gulfstream jet with George Low, senior manager of the Apollo spacecraft program, and Low’s secretary. On the morning of July 9, 1969, at 4 a.m., Kinzler supervised its installation on the lunar module.

On the Moon on July 20, 1969, both Armstrong and Aldrin had a printed checklist sewn onto the broad cuff of their left spacesuit glove, so they could glance down and see where they were in their tasks during their two-hour Moon walk.

Setting up the flag wasn’t on the checklist. It had come too late to be included.

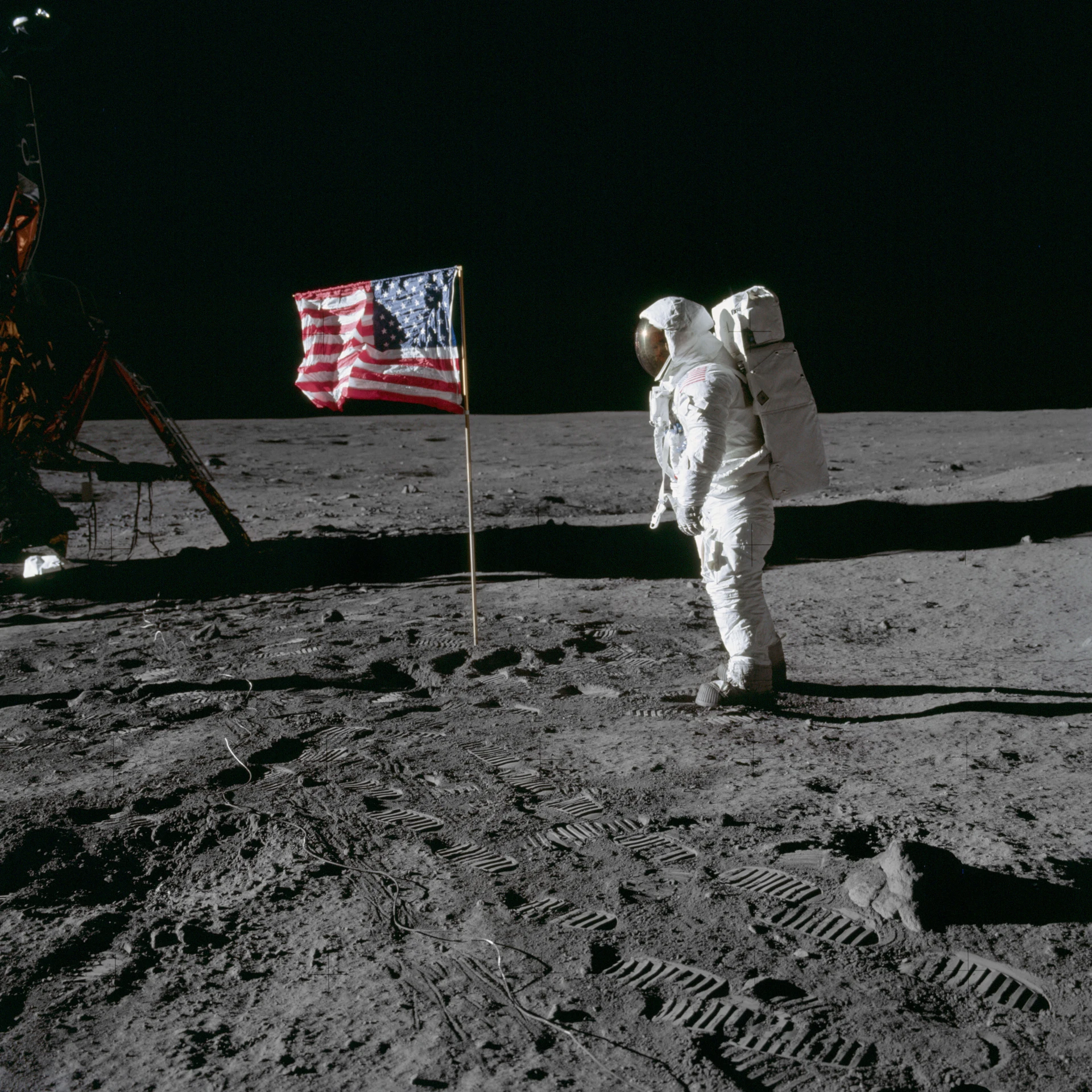

Armstrong and Aldrin didn’t make a big show of the flag planting. Indeed, over the Moon-to-ground link, they didn’t talk about it at all, nor did they turn it into much of a ceremony, even as 600 million people watched.

And the process didn’t go as well as they would have liked.

“It took both of us to set it up and it was nearly a disaster,” Aldrin said. “To our dismay the staff of the pole wouldn’t go far enough into the lunar surface to support itself in an upright position.”

That’s what can clearly be seen on the TV broadcast—Armstrong trying over and over to get the flag planted securely in the rugged ground. “After much struggling,” continued Aldrin, “we finally coaxed it to remain upright, but in a most precarious position. I dreaded the possibility of the American flag collapsing into the lunar dust in front of the television camera.”

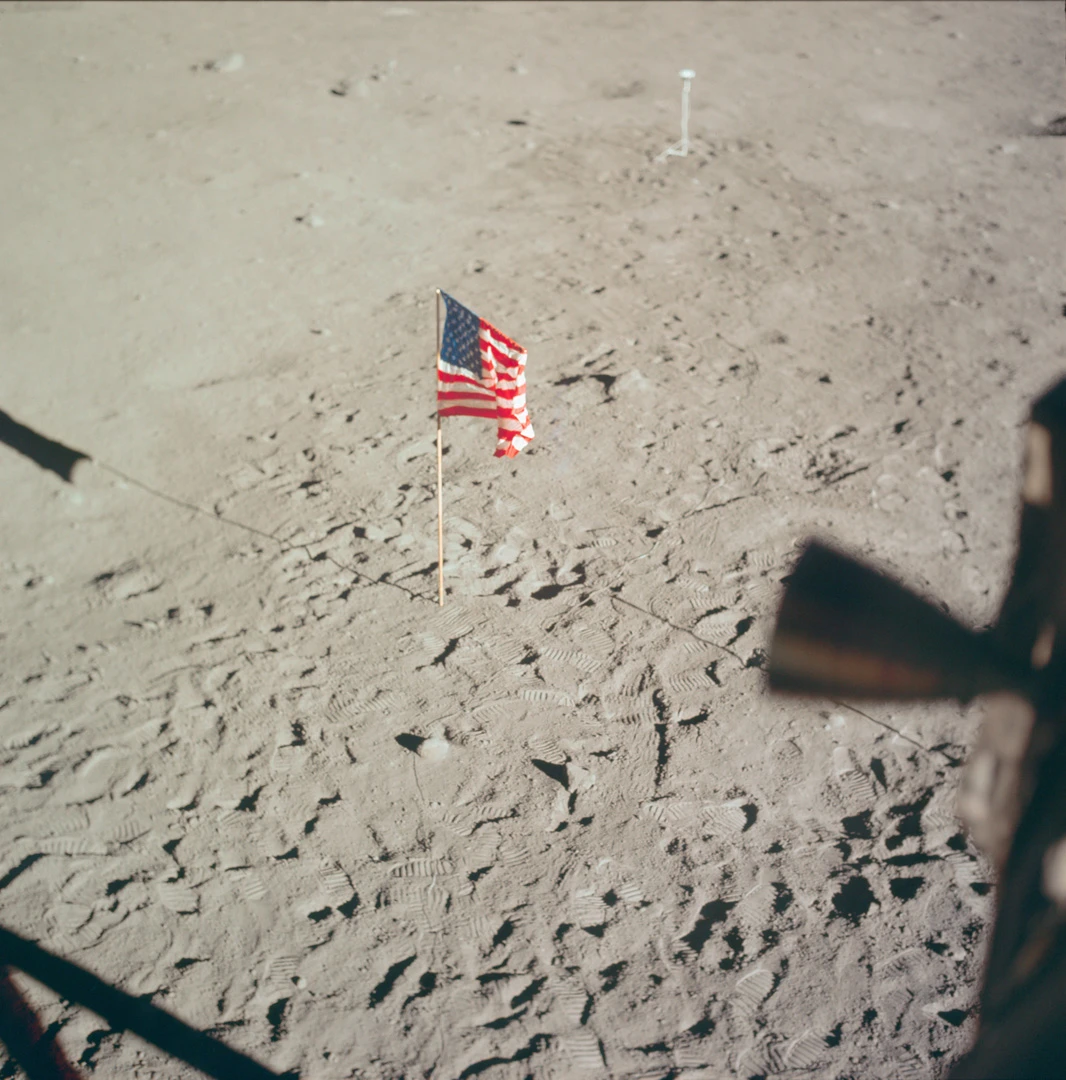

It didn’t, at least not then, and not on camera. (It was knocked over when Armstrong and Aldrin took off from the Moon, by the blast from the lunar module’s ascent engine.)

The reason Armstrong and Aldrin had so much trouble with the flag was that they ignored Kinzler’s instructions and training. The flag was specifically designed so the bottom section of the vertical pole could be hammered into the ground separately, using a geology tool. The top part of that pole had been hardened so it could be hammered on. Armstrong and Aldrin skipped that; they assembled the flag pole, including extending the rod that allowed the flag to “fly,” before trying to get the pole itself into the ground, which accounts for their awkward maneuvering.

Walter Cronkite, narrating the first Moon walk for CBS News, explained to TV viewers how the flag worked. “There is no wind to hold it out like that, of course. It’s a three-by-five flag. It’s got a frame of its own to hold it out like that.”

Cronkite paused. “Nothing more really is needed here, but it does seem like there ought to be some music,” he said, chuckling. He explained that the astronauts weren’t “claiming” the Moon with the flag—and couldn’t anyway, because of the U.N. treaty. “So this planting of a flag is not the old 15th, 16th, 17th century business of planting a flag and claiming territory. It’s to put the United States flag there to let the world know that we are there. To sense the pride the American people feel in this tremendous accomplishment and the contribution they have made to it.”

In newspapers in the U.S. and around the world, the grainy black-and-white photo of Armstrong and Aldrin alongside the flag was the picture in the top position.

Some at NASA thought the Apollo 11 flag deployment had served its purpose. George Low wrote a memo to Bob Gilruth, the head of the Manned Spacecraft Center, saying he and his colleagues had “tentatively decided not to emplace any more flags on the lunar surface. There will, of course, always be a flag painted on the (lunar module), but my view was that it would not be necessary to go through a flag-raising ceremony each time we go to the moon.”

But the power of the flag deployment overruled Low. Kinzler’s records show that in October 1969, NASA managers had decided to send a flag with each mission, and Kinzler’s team assembled the kits.

President Kennedy had foreshadowed the moment. In his September 1962 speech at Rice University, Kennedy used the flag to represent human inspiration and aspiration.

“No nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in this race for space,” he said. “We have vowed that we shall not see [space exploration] governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace.”

Charles Fishman, who has written for Fast Company since its inception, has spent the past four years researching and writing One Giant Leap, his New York Times best-selling book about how it took 400,000 people, 20,000 companies, and one federal government to get 27 people to the Moon. (You can order it here.)

For each of the next 50 days, we’ll be posting a new story from Fishman—one you’ve likely never heard before—about the first effort to get to the Moon that illuminates both the historical effort and the current ones. New posts will appear here daily as well as be distributed via Fast Company’s social media. (Follow along at #50DaysToTheMoon).

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.