This is the 37th in an exclusive series of 50 articles, one published each day until July 20, exploring the 50th anniversary of the first-ever Moon landing. You can check out 50 Days to the Moon here every day.

The most harrowing moment in the new three-part PBS series Chasing the Moon, about the race to the Moon in the 1960s, happens on Earth, in the suburban home of astronaut Frank Borman, near the Manned Spacecraft Center south of Houston.

Over an excruciating 20 minutes, we get to watch Borman’s wife, Susan, as she watches her husband and his crewmates blast off in December 1968, on Apollo 8, that first trip to the Moon.

Susan Borman is sitting on the floor in the family room, her back against the plaid couch. Her sons are on the couch behind her. They are watching the family’s black-and-white TV, which is sitting, as was common in those days, on a wheeled cart.

Along one wall of the room stand 14 friends and visitors, also there to watch, one of whom is a priest. It’s real life, and you have to keep reminding yourself of that, because the colors are so vivid, the tension so palpable, it feels cinematic.

On the kitchen counter, a large red can of Folgers coffee. The Borman refrigerator is a 1960s brown side-by-side. On top of the refrigerator, a china tea kettle and serving dishes.

There’s a brief flash of the TV crew setting up lights and camera. If you pay attention, you can see a microphone, camouflaged by a candle centerpiece, sitting on the coffee table inches from Susan Borman’s face.

How Frank Borman, the commander of the Apollo 8 mission, came to have a TV crew in his house, recording every moment, every facial expression, of his family during what was only the second time the giant Saturn V had launched with people atop it—that, too, is instructive.

It had been almost two years since the Apollo 1 launchpad fire killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. Susan Borman was close friends with the new widow Pat White, who lived right nearby. Frank Borman, interviewed for this documentary, says, “The fire shattered my wife’s confidence in NASA and in the Apollo program.” He notes that supporting Pat White had, in part, led his own wife to starting drinking too much.

Approaching their own pioneering flight, Borman says, “NASA wanted me to allow a film crew to come into the house while we were up on our way to the Moon.

“I mentioned this to Susan, and she was opposed to it. She didn’t want it. But I said, ‘Look, this is going to be important for the space program.'”

At a moment when Borman’s wife is struggling to help a friend whose astronaut husband was killed in a spaceship, and her own husband is about to try to fly to the Moon in just such a spaceship, Borman says he “mentions” the TV crew to Susan, as if an actual discussion of this level of personal invasion by the media wouldn’t ever occur to him—even 50 years later.

Apollo 8, of course, was a triumph, a perfectly executed flight from the launch to the reading of Genesis by the astronauts on Christmas Eve while in lunar orbit. The Apollo 8 astronauts brought back one of the most famous photographs ever taken: the “Earthrise” picture of the Earth floating in black space over the surface of the Moon.

But at no point does Susan Borman, the wife of the mission’s commander, look anything but miserable.

A thin black headband holds her hair back and her lipstick is bright red and perfect, but as she watches the countdown and then the launch, her hands are covering her mouth. She looks as if she’s just come from a funeral. Once Apollo 8 is safely in orbit, she pushes her fists against her cheeks, and squeezes her eyes shut. You can occasionally see her hands shaking faintly.

Jules Bergman, ABC’s renowned space correspondent, says, “Borman, Lovell, and Anders off perfectly!” Susan Borman doesn’t smile, doesn’t look relieved. She just puts her face in her hands. Behind her, one of her sons rubs her shoulder.

And that’s how she looked with total, jubilant success.

A couple hours later, Susan Borman stands on her own front lawn. The reporters and cameramen are crowded into the bushes trying to get a question in, trying not to miss a word. The commander’s wife has changed from pants to a cream-colored dress. She is wearing a string of pearls. She looks and sounds a little blurry. Valerie Anders, the wife of one of her husband’s crewmates who also helps narrate the documentary, says of this moment: “The reporters never really left.” Anders said she couldn’t bear to go out on the front lawn of her house and face them.

Susan Borman looks a little wide-eyed, and also a little wry.

“Really, I’d love nothing better than to make a beautiful, profound statement for you that would be earthshaking for everybody,” she says. “But really, I’m just speechless.”

Three big documentaries

What’s interesting and original, and feels fresh, about Chasing the Moon—one of three big documentaries in the last six months to mark the 50th anniversary of the first Moon landing by Apollo 11, July 20, 1969—are the parts like that, the ones that tell us something we didn’t know or have lost track of about both the race to the Moon and the 11 years during which it played out.

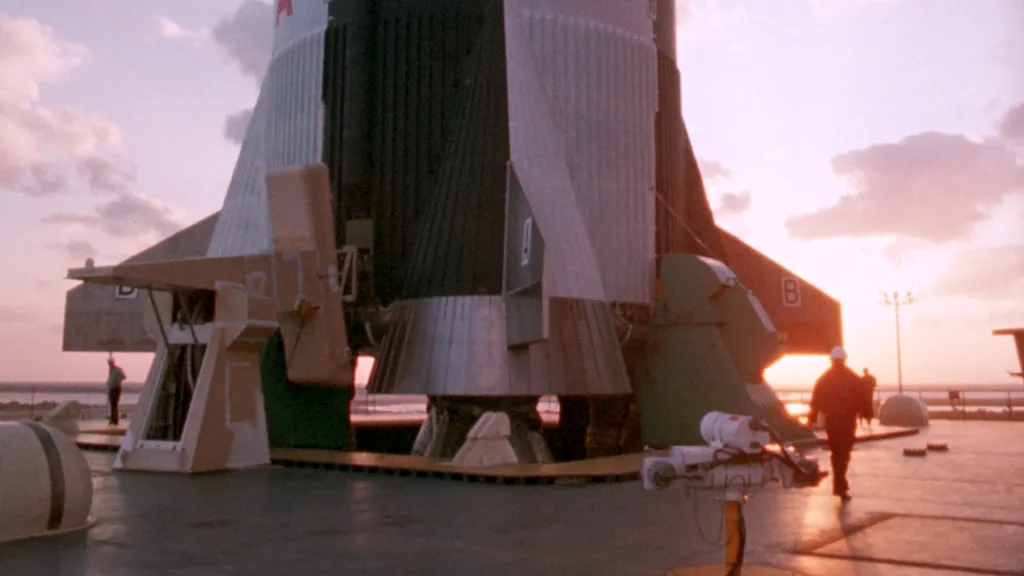

Apollo 11, which premiered in March and was released in theaters before airing on CNN in late June, is built on never-before-seen wide-format film shot at the time of the launch, and of the mission itself. The film is extraordinary—ranging from intimate views of the astronauts headed to the capsule for launch to sweeping panoramas of the 1 million people who crowded the east coast of Florida to watch. The quality of the filming is so arresting, you have to constantly remind yourself that there are no actors: Everyone is a real person.

You can see it again on CNN on the anniversary itself, July 20—and you should.

National Geographic’s entry in the Moon-landing documentary lineup, Apollo: Missions to the Moon, premieres tonight, Sunday, July 7, on the National Geographic channel. The NatGeo documentary is 90 minutes long, and tries to capture the full sweep of the era and all the Apollo missions in that time. A few words about it in a minute.

PBS’s ‘Chasing the Moon’

Chasing the Moon, from PBS, premieres tomorrow, Monday, July 8, at 9 p.m. ET on PBS stations, and runs at 9 p.m. for the next two nights as well. Chasing the Moon is part of PBS’s American Experience franchise, and it is the most ambitious of the three documentaries.

Running six hours over three episodes, director Robert Stone gives himself more than enough room to tackle the rivalry with the Russians that led to the race to the Moon, the cultural tumult in the U.S. that was happening right alongside it, the space missions themselves, and a glimpse at the personalities involved.

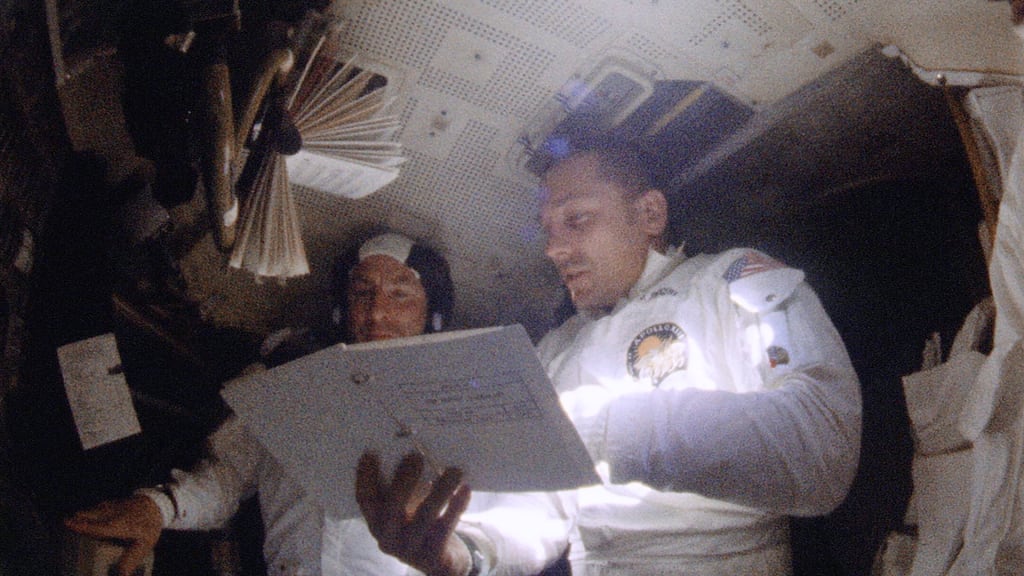

All three Apollo documentaries are unnarrated: They rely on the voices heard on-screen to guide viewers through the story. But unlike the other two, Chasing the Moon takes a more active role in the storytelling. The filmmakers have fresh interviews with both surviving Apollo 11 astronauts, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, along with two of the three astronauts of Apollo 8, Borman and Anders (Jim Lovell, 91, was not interviewed). None of these people appear on screen. Their voices are just part of the storytelling that pulls the viewer along.

But they offer revealing moments. Aldrin says he and Collins were, in fact, curious what their commander, Neil Armstrong, intended to say when he first put a foot on the Moon.

During the flight out to the Moon, says Aldrin, Collins “asked him, ‘Have you thought about what you’ll say?’ Neil said, ‘Nah. Nah. I’ll wait ’til I get there.’ I don’t think Mike believed him, and I didn’t either.”

For the record, that’s what Armstrong has always said—he didn’t think about it until they actually landed on the Moon—and lots of people besides his crewmates found that unlikely for a military test pilot who liked things prepared, practiced, and squared away.

The best parts are film footage of things that haven’t been seen in decades, or perhaps ever. There’s lots of behind-the-scenes film of the Soviets working on their space vehicles (though some on-screen captions telling us what we’re seeing would have done that especially rare footage more justice). There are several bursts of video of the anti-poverty protests led by the Rev. Ralph Abernathy at Cape Kennedy the day before the Apollo 11 launch, including footage of NASA Administrator Tom Paine coming out to meet and speak to the protesters, and to listen to them—a reminder that public officials didn’t always regard the actual public as an inconvenience.

There is a clip of a lounge singer in Cocoa Beach, Florida, during Apollo’s go-go years and therefore the town’s boom time, telling her barroom audience, “Welcome to Cuckoo Beach, the government-controlled Disneyland.”

The film wisely takes advantage of its length to venture into the role of women in NASA, and to tell the damned disappointing story of Ed Dwight, America’s almost-first African American astronaut. Alas, it doesn’t give even a taste of the work that Apollo required of the people who made it possible—outside the astronauts, their wives, and Mission Control. We never hear from any of the people who had to solve the problems necessary to get people to the Moon, from MIT’s computer engineers to the spacesuit seamstresses. It would have been nice to spend 20 minutes out of nearly 360 with the people who did the work to make the voyages possible.

Chasing the Moon also frankly flubs the Apollo 11 Moon landing itself. The drama of the landing—13 minutes that quickly turn tense and harrowing—is confused and deflated by constant cut-aways to random audiences around the world watching those 13 minutes on TV.

But those are storytelling quibbles.

Six hours is a significant viewing commitment, although it seems less so in the era of binge watching. But Chasing the Moon never seems too long, and never drags.

National Geographic’s ‘Apollo: Missions to the Moon’

National Geographic’s Apollo: Missions to the Moon, on the other hand, is unsatisfying, especially when compared with its contemporary rivals. It’s dramatically shorter—at 90 minutes, less than the length of one of the installments of Chasing the Moon. But Missions to the Moon attempts to cover more terrain, at least chronologically, spending almost a quarter of that time on Apollo 13, for instance (Chasing the Moon ends, essentially, with Apollo 11’s first landing).

The result can be a little jarring if you know the story. Despite the focus on Apollo 13, one of the most important and innovative parts of that story—how Mission Control and the astronauts solved the problem of cleaning carbon dioxide out of the spacecraft air—isn’t mentioned.

Small events are shown, over and over, slightly out of chronological order. Missions to the Moon, too, doesn’t have a master narrator, but much of the on-screen narration is provided by the coverage of Apollo, at the time, from the BBC. Perhaps that’s an effort to “internationalize” the documentary for National Geographic’s wider audience, or to steer away from the more familiar TV network anchors Walter Cronkite and Frank Reynolds and Jules Bergman. But the result simply feels off-key for such an American event.

Missions to the Moon does excavate some lesser-known moments. An image of the Pope watching the Moon landing. Video of crowds gathered in Central Park, before a big screen set up by ABC News, to watch the Moon walk, an event the TV anchor called a “Moon In.” The prayer services around the country held on behalf of the Apollo 13 astronauts during the five days they were desperately trying to fly their crippled spaceship home.

Both Chasing the Moon and Missions to the Moon have a little trouble figuring out how to wrap up, and end up relying on voice-overs that are wistful because of their optimism.

At the end of the National Geographic film, an on-screen commentator says, “We are not putting our rockets in the barn and closing the door.”

At the end of Chasing the Moon, an on-screen commentator says, “A new chapter in human history has opened.”

In fact, since Apollo 17’s last voyage to the Moon in 1972, not even one person a month, on average, has been launched into space—hardly the bustling “space age” of those post-Apollo hopes.

The good news is that, 50 years after those Moon landings, there’s a good chance that Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are, in fact, flinging open the barn doors on a new era of human space travel.

Charles Fishman, who has written for Fast Company since its inception, has spent the past four years researching and writing One Giant Leap, his New York Times best-selling book about how it took 400,000 people, 20,000 companies, and one federal government to get 27 people to the Moon. (You can order it here.)

For each of the next 50 days, we’ll be posting a new story from Fishman—one you’ve likely never heard before—about the first effort to get to the Moon that illuminates both the historical effort and the current ones. New posts will appear here daily as well as be distributed via Fast Company’s social media. (Follow along at #50DaysToTheMoon).

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.