There’s a chart at Mattel that undoubtedly keeps its VPs up at night. I saw it on a slide during a corporate presentation. And while the company wouldn’t share it to be reprinted here, let me paint you a picture the best I can remember it. The Y-axis is time spent playing. The X-axis shows age. The first line depicts kids who play with physical toys—cars, dolls, and other products Mattel is known for. The other line shows kids who play with tablets and phones—apps on Android and iOS devices. The physical toys start high. The screen toys start low. But by age 6, these two lines grow close. And by age 8, they cross. Children are barely in their preteen years as they leave toys as we know them behind, these days.

And that’s why, despite Hot Wheels being the number-one selling toy in the world—the average U.S. child owns 50 Hot Wheels, according the company, and 500 million of these die-cast cars were sold in 2018 alone—Mattel has spent the last four years rethinking Hot Wheels for the digital age.

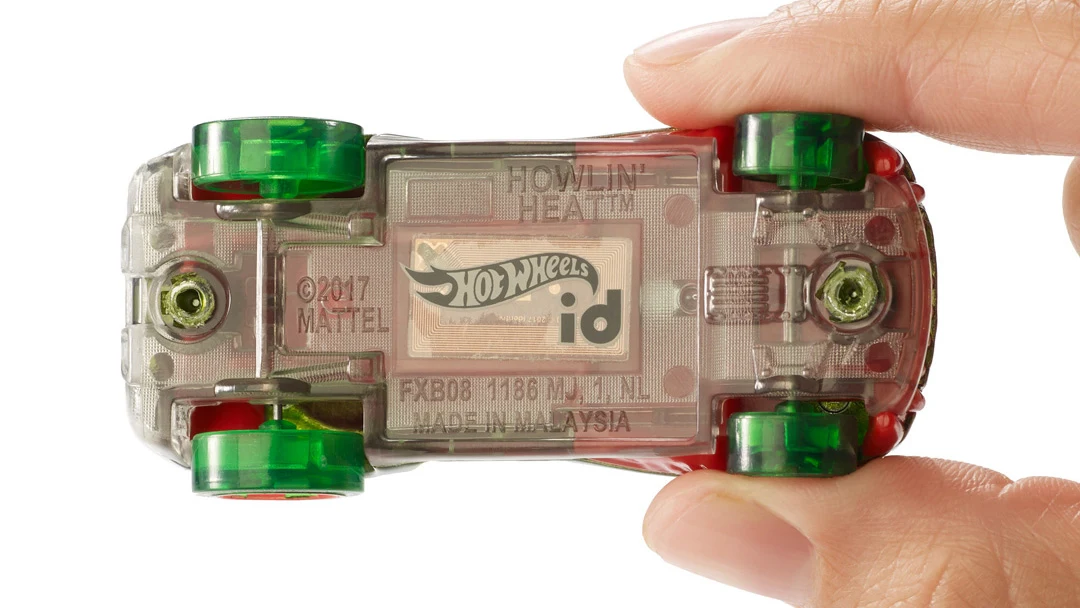

Today, Mattel is launching a new product called Hot Wheels ID. It’s a premium, $7 version of the $1 Hot Wheels cars you know. Nearly identical to the Hot Wheels produced for the last 50 years in every way, these vehicles sport one important update: They have been retrofitted with NFC chips, so they have a digital identity, too.

That means Hot Wheels ID vehicles—using new track designs and components that accompany the release—will connect seamlessly to the cloud, which records their vehicle and race history like a Carfax report. Using iOS and Android apps, but playing with Hot Wheels much like they always have, kids will see their top speeds, lap times, and how they stack up to the world’s Hot Wheels drivers. In one game mode, called Slingshot, you launch your vehicle on a physical Hot Wheels track, then you look to the screen as a digital copy flies through a flaming hoop like Angry Birds. Kids will also be able to race digital versions of their cars inside the apps, too, without buying die-cast vehicles at all, leveling up their performance and paying to unlock new features through micro-transactions.

What Mattel hopes it has created is a version of Hot Wheels that’s true to the last 50 years of the brand, but future-proofed for decades to come.

“We’re by far the leader in the space,” says Chris Down, chief design officer at Mattel. “But there are barbarians at the gate. I don’t want to get caught not recognizing what consumer behavior is gravitating toward with a 50-year-old brand under my watch.”

In late 2015, before Down’s promotion and when he led only Hot Wheels, Mattel was considering entering a category of toys typically called “Toys to Life” in the industry. These are usually plastic statues, like Nintendo’s Amiibo figures or Skylanders, which, using NFC chips, unlock characters and other digital experiences inside video games. For Nintendo, Amiibo alone is a business that generates more than $100 million in revenue a year. But the problem, as Mattel designers noted, was that these physical toys were mostly just a lock and key. You bought the figure, but it was built for your shelf. The game part was entirely digital.

In 2016, Hot Wheels designers began exploring the potential of putting NFC chips into the cars, like Amiibo. These chips cost a mere 10¢, but they would allow Hot Wheels to unlock digital experiences, too. The problem remained to be solved, though: If you built NFC into a Hot Wheels car, what should it do to add to the experience?

“It is important to get the tech right and the play right,” says Sven Gerjets, CTO at Mattel (whose first major act at the company was to kill Aristotle, Mattel’s attempt at creating a voice assistant for children, which endured withering criticism from privacy experts). “Otherwise you’re creating a novelty experience.”

So Mattel, teaming up with Ideo, spent 12 weeks doing ethnographic research and going inside homes to identify how kids played with Hot Wheels and played in general. They learned, yes, kids love tech. If a toy had an app, it was inherently cooler than if it didn’t. But perhaps the most key takeaway was that kids want challenge—an ever-ongoing, ever-greater challenge. It’s the very model that made video games so popular.

In 2017, as Mattel’s team was still debating the project, representatives from Apple showed up to Mattel’s L.A. campus. “We showed them ideas across the entire Mattel portfolio. Monster High. Barbie. Whatever,” recounts Down. “The last slide of the presentation deck was just labeled ‘NFC smart cars.’ It was the one thing Apple leaned forward to and . . . wanted to know more about.”

No doubt, those Apple representatives knew that the upcoming iPhone would have NFC built in for the first time. The validation from Cupertino, especially given that he was already confronting some dissent on the idea internally, helped cement Down’s vision of “a chip in every car,” he says. “If you could add a [gamification] benefit to how kids play with Hot Wheels to the number-one selling item on the planet, you have such a mass and draw.”

Mattel decided NFC Hot Wheels would arrive in 2018, for the 50th anniversary of the brand. Of course, things don’t always go as planned. Down readily admits to some infighting. Both his business and marketing teams pushed back on the idea. “This is classic disruptive innovation organ rejection,” says Down. “You know it’s something good for you, but it’s going to be eaten by the rest of the body because it has business to do.”

Eventually, Down went so far as to send Ron Friedman, director of product management and global brand marketing, to product management school. Without business or marketing departments on his side, he needed an ally who could help him develop a quantified pitch and business model that would prove out ID’s revenue potential. Down handed this plan right to Mattel’s CFO, who then signed off on the project. Shortly thereafter, the new CTO, Gerjets, arrived at Mattel to help Down build a unified digital back end—not just to launch Hot Wheels ID, but to allow Mattel to launch all sorts of physical and digital toys down the line. This platform is COPPA- and GDRP-compliant, and Gerjets promises to try to always collect the minimum unidentifiable data that enables gameplay.

But crucially, the track feels wonderful as an analog toy, too. The car launcher, which you press on to rev up before it fires your car down the track, feels particularly satisfying to push. It’s just a plastic toy, but it revs up with the sound of an engine. I wish I could start my lawnmower with such a button. It’s mechanical toy design at its best.

As for the digital end, I’m not sure that I’m sold. No single app function I was shown seemed like a must-have, must-play feature. But Down admits that NFC isn’t an end point for Hot Wheels, but a starting point. With this hardware, apps can see toy cars for the first time. Software updates can unlock new features for physical toys years later. And if Hot Wheels ID is a success, in 5 or 10 years, every Hot Wheels car could have these chips installed.

Regarding Mattel’s other brands that seemed destined to go digital, too—like Barbie—don’t expect them to take the same approach Mattel took with Hot Wheels ID. “There’s a natural [crossover] for racing. Using that in Barbie is not natural. Kids don’t want to be playing and all the sudden have to scan their doll,” says Gerjets. “Finding the right tech for the play pattern is key. For Barbie, kids want to be open ended, tell stories, make stories, share, be social. I don’t want them to have to stop doing that.”

The market will decide if that happens next for Hot Wheels ID. The $180 Smart Track, $40 Race Portal, and $7 cars will launch exclusively at Apple Stores first, today, much like the now-defunct Anki AI car racing track. It is, perhaps, not the best omen for Hot Wheels, but that’s not stopping Down from being optimistic about Mattel’s future. “The fact of the matter is we don’t know Hot Wheels ID is going to be the raging success we hope it will be,” says Down. “But the greatest benefit we get, even if we shut down in a week, is that we have started to develop a new muscle in how to recognize innovation, and find ways inside this massive, 75-year-old company to bring things to market.”

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.