This is the seventh in an exclusive series of 50 articles, one published each day until July 20, exploring the 50th anniversary of the first-ever Moon landing. You can check out 50 Days to the Moon here every day.

Cigarettes show up in unlikely–and occasionally unsettling–places in the race to the Moon.

People making critical pieces of spaceship equipment smoked.

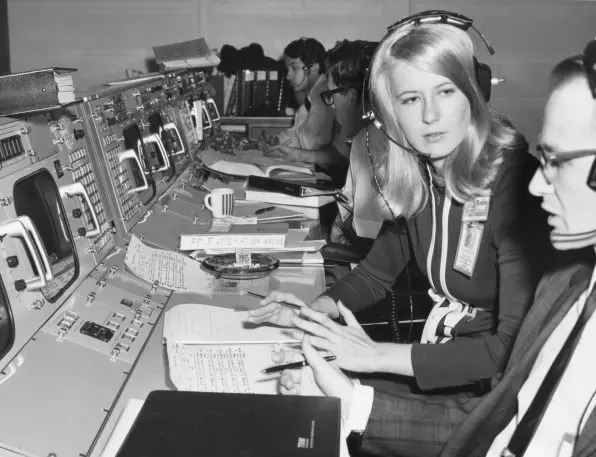

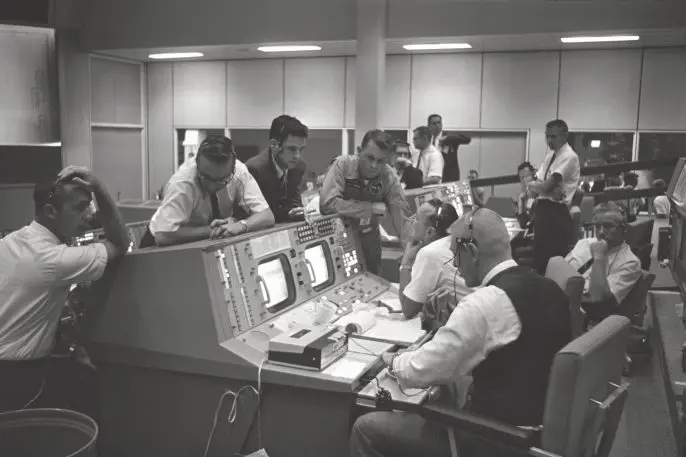

People running Moon missions smoked.

Astronauts smoked.

The country smoked.

In 1965, 52% of adult men in the United States smoked, and 34% of women did.

At the press conference where the Mercury 7 astronauts were introduced–America’s first-ever astronauts–on April 9, 1959, three of the seven astronauts smoked on stage during their introductions to the nation (Deke Slayton, Alan Shepard, and Wally Schirra). Also smoking on stage, during the press conference: Brig. General Donald Flickinger, the Stanford-educated flight surgeon who was one of the people in charge of picking the astronauts. The third question from a reporter, in fact, was a half-joking inquiry about it. “I notice that three of you are smoking,” he said, “and I wonder what are you going to do for cigarettes when you get up in the capsule?”

In the 1960s, when there were almost no restrictions on where people could smoke, smoking was not an idle habit. Pilots smoked in the cockpit while flying, and doctors smoked making rounds in hospitals. The typical smoker was going through 29 cigarettes a day (a pack and a half), a cigarette every 35 minutes while they were awake.

Thomas Kelly, the chief engineer at Grumman for the design and construction of the lunar module, routinely visited the factories of companies supplying parts for the Moon lander. In 1966, he was particularly appalled by what he found at Eagle Picher, the Joplin, Missouri, company that manufactured the batteries that provided all the electrical power for the lunar module while it was flying to the Moon. The lunar modules themselves were assembled in clean-room conditions, with everyone who touched the Lunar Modules wearing coveralls, hairnets, and gloves. At the battery factory, as he recounts in his memoir Moon Lander, Kelly found an un-air-conditioned building, with its windows open and its workforce smoking as they assembled the batteries. “One muscular fellow caught my eye particularly. He was wearing a soiled undershirt and had a cigarette dangling from his lips. As I watched incredulously, the ash on his cigarette grew longer as he peered over the open (battery) case into which he had just placed a plate assembly, until it finally broke off and fell inside.” Kelly was so furious, he ordered a Grumman quality-control inspector assigned permanently to the Eagle Picher factory.

In his left hand, a cigarette.

Ronald Evans was the command module pilot for Apollo 17, the last Moon landing mission. His crewmate, Gene Cernan, in Cernan’s memoir The Last Man on the Moon, says Evans “smoked the last cigarette he would have for two weeks” while the astronauts were putting on their spacesuits before boarding the Saturn V rocket for launch. When Apollo 17 splashed down in the Pacific, Cernan writes, “one of the first things (Ron did) was bum a cigarette from a sailor.”

Charles Fishman, who has written for Fast Company since its inception, has spent the last four years researching and writing One Giant Leap, a book about how it took 400,000 people, 20,000 companies, and one federal government to get 27 people to the Moon. (You can preorder it here.)

For each of the next 50 days, we’ll be posting a new story from Fishman–one you’ve likely never heard before–about the first effort to get to the Moon that illuminates both the historical effort and the current ones. New posts will appear here daily as well as be distributed via Fast Company’s social media. (Follow along at #50DaysToTheMoon).

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.