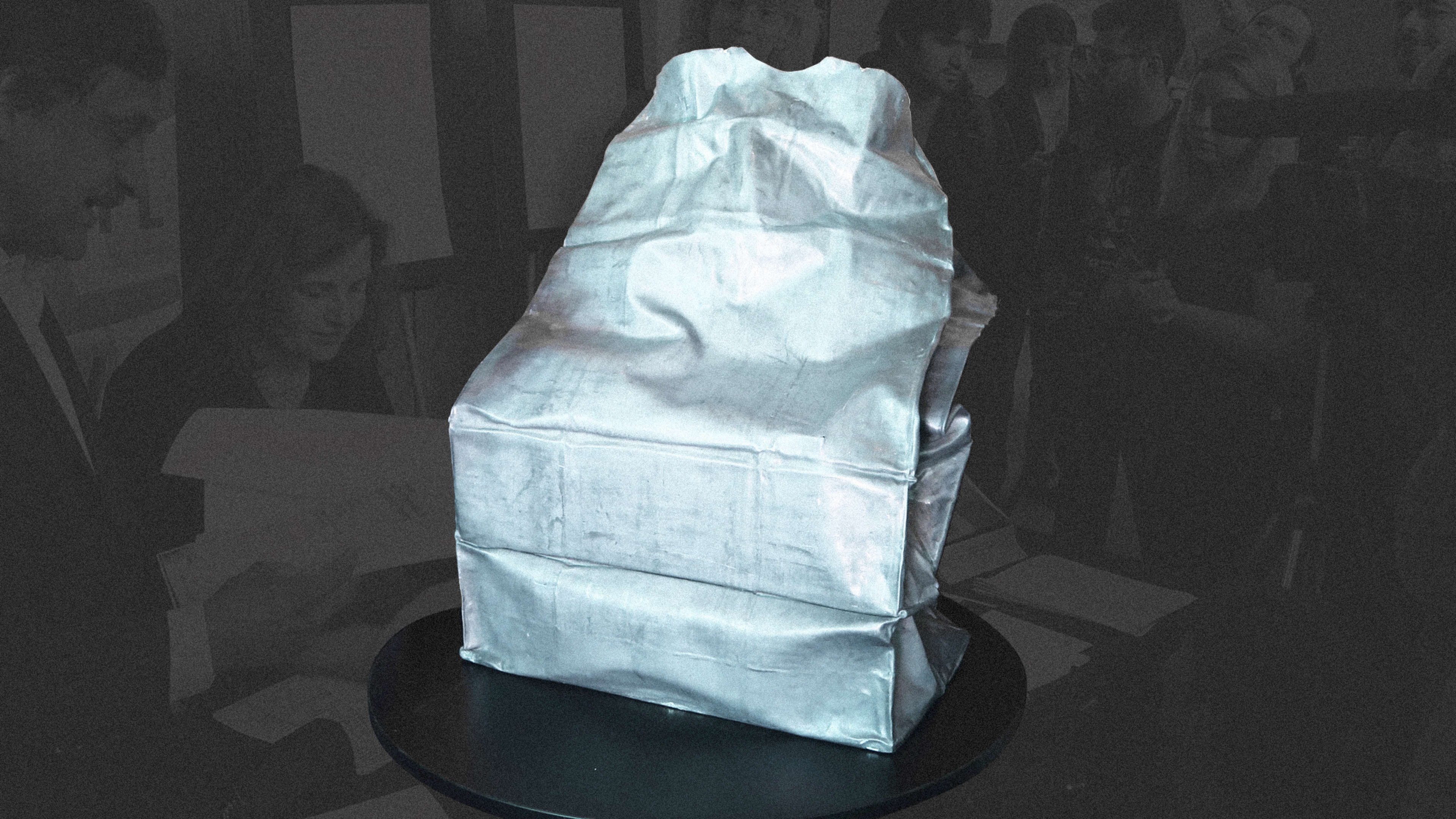

In 1999–which may as well be 5,000 BC in internet years–the Laboratory for Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology buried a time capsule.

The package, which was designed by architect Frank Gehry, contained internet history. Its contents were protected by a cryptography puzzle designed by MIT professor Ron Rivest, meant to keep it safe for decades. However, on May 16, the self-taught Belgian programmer Bernard Fabrot solved the complex calculation, which required 80 trillion successive squarings of a number. So two decades after the time capsule was buried, it’s been unearthed, thanks to the unpredictably fast advance of technology.

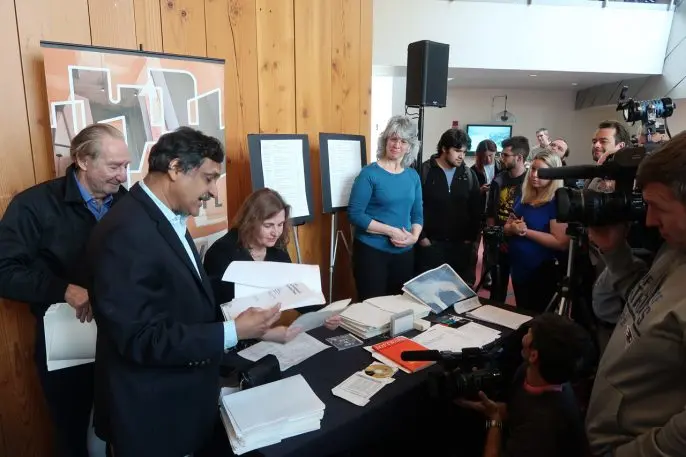

Inside, they found Tim Berners-Lee’s original proposal for the World Wide Web, written in 1992. This document laid out the rules that governed the HTTP protocol and how the HTML language was supposed to work–describing the graphic appearance of content on the internet, and how links would connect everything in a web-like network of nodes that could take you from a page about the mating habits of penguins to one that describes how a steam locomotive work. Basically, the document is one of the primary reasons you’re able to read these lines right now.

The capsule also included Microsoft’s first ever product, the BASIC interpreter that Bill Gates and Paul Allen coded for the Altair computer in 1975. The Altair was one of the first popular personal computers among nerds, who had to operate it with switches rather than through a screen. Gates and Allen’s work in the BASIC language for that platform positioned them to work with Apple on the Applesoft BASIC interpreter for the Apple II, which was a dialect of Microsoft’s.

So began the relationship that brought Gates and Jobs together. Microsoft eventually released Word for Macintosh, which led to the creation of its own graphic interface that sat on top of MS-DOS: Windows.

And finally, the directors rediscovered a 1962 MIT paper that defines how to share a computer’s processing power among several people at the same time. This idea of “computer time-sharing” is what enabled millions of people to read this page, order things, or write a document concurrently. Basically, it’s the science that made our current technological reality possible.

According to Rus, this wasn’t the only capsule buried on campus. Another, buried under the MIT’s Cyclotron building, is scheduled to be unearthed when the school starts construction on a new building on that site. And a third capsule (seen in the video above) was buried in 1957, only to be inadvertently uncovered by a construction crew in 2015. MIT didn’t disclose the contents of the hermetically sealed glass container, which is filled with the inert gas argon to prevent the decomposition of its contents until it’s due to be opened more than 900 years from now, in 2957.

I don’t know how they find the strength to resist.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.