If you watched the recent series finale of Game of Thrones, then you already know that the Iron Throne, the ultimate symbol of power in Westeros, took a real beating.

“Have you ever seen the Iron Throne? The barbs along the back, the ribbons of twisted steel, the jagged ends of swords and knives all tangled up and melted? It is not a comfortable seat, sir. Aerys cut himself so often men took to calling him King Scab, and Maegor the Cruel was murdered in that chair. By that chair, to hear some tell it. It is not a seat where a man can rest at ease.”

You have to hand it to George R.R. Martin. It’s hard to imagine a more imposing symbol of power than a throne forged from the melted weapons of vanquished foes. In fact, in his original conception the throne was even more massive and sprawling, a violent scrap heap on which the poor ruler would perch uncomfortably. The show’s designers scaled that vision back into a more conventional form that we might associate with a medieval king, with the swords fanned out behind like some sort of gruesome peacock. While it is not based on any specific historical reference that I can think of, you might consider the imposing throne of Ivan the Terrible, made from the massive tusks of elephants and carved with old testament battle scenes, for a somewhat comparable symbol of power (elephants were once used as terrifying weapons of war–Queen Cersei herself was quite disappointed to discover that the army she purchased from the Golden Company at the beginning of this season did not include any of these powerful beasts).

But why would anyone design a throne to be so uncomfortable? With all of the privilege and power of the seven kingdoms at your fingertips, why not make some minor adjustments so that the throne is a bit more cushy (a royal lumbar pillow perhaps)? This question hints at a fundamental shift in our expectations of design, a shift that has shaped the user-friendly age we find ourselves in today. The evolution of seating–not just for fictional royalty like Aegon Targaryen, but also real-life figures like Louis XV and even today’s CEOs and politicians–can tell us a lot about the emergence of user-friendliness in our culture.

Discomfort and Divine Right

It is not surprising that medieval thrones were designed around different notions of power and privilege than we live with today. The occupants ruled by divine right, so their personal comfort was beside the point. Divine right required that monarchs project a godly authority by sitting stiff and upright at all times, not slouching or reclining (as the Romans were famous for).

Today, we live in a time in which an authoritarian-style of leadership is increasingly in vogue. While the Oval Office certainly projects the authority of the POTUS, the design is more suggestive of a CEO than a divine ruler. Given his fetishization of all things baroque, it wouldn’t have been that surprising if Trump had installed a golden throne with a royal “T” somewhere in the White House (perhaps the press briefing room?). Yet neither Trump, Putin, Erdogan, nor Xi rely on thrones to project their authority, preferring more casual images that reinforce their connection to everyday people. Today, we take it for granted that power and privilege should come with much greater ease of use, whether through the cushy design of a corporate jet or a $1,000+ smartphone.

When did this shift toward comfort and ease as symbols of power and privilege begin?

According the technology historian Edward Tenner, it can be traced back to French royalty in the 18th century. No detail was left to chance in the design of the massive palace at Versailles, where each element of the interior was raised to the level of fine art. This resulted in an explosion of sumptuous new designs for furniture and seating, with each room being carefully curated around the social dynamics of the royal court. In this environment, the French king was the only person permitted the comfort of sitting in a padded armchair. Members of his royal entourage were provided somewhat less comfortable armless chairs, with backless stools for nobility of lower standing, and unpadded folding stools for the most minor figures in the court, according to Tenner: “The kings of France would impose their will on the aristocratic parliaments while reclining in a formal ceremony called lit de justice, but the point of the monarch’s ease was to dramatize his power over the assembled sitting, standing, and even kneeling subjects.”

The social order was encoded into the design of the furniture, with comfort as the key signifier of privilege–rather than the rigid formality of earlier royal thrones. If Tyrion Lannister were to assume the throne and rule Westeros, by some strange twist of fate, it is easy to imagine him projecting his authority in a similarly casual manner, perhaps with a generous goblet of wine in his hand at all times.

Today, ease of use has become a core attribute we expect from a “premium” experience. People will pay more for products and services (like Apple’s) that serve our needs and reinforce our sense of privilege and comfort, even at the expense of others (as in the case of Uber drivers).

From First-Class Thrones To La-Z-Boys

The best analogy for a modern-day throne might be the increasingly mammoth, flatbed seats on international flights. Few experiences today reinforce a stronger sense of privilege (or the lack thereof) than the ritual of parading through first class on your way to the increasingly cramped seats in steerage. In fact, the design of economy seats has more in common with medieval thrones–forcing occupants into a stiff, upright posture for long periods of time–than the technological and design marvels up in first class.

Airline seating has been touched by many leading industrial designers, including Walter Dorwin Teague in the 1940s, Henry Dreyfuss in the 1950s (the first to consider them appliances, not furniture), and Hartmut Esslinger, who worked with Lufthansa in the 1990s.

But the design of modern, adjustable airplane seats has a heritage that stretches back long before the rise of industrial design in the early 20th century. Adjustable mechanical seating was originally developed to support the disabled, but in the 16th century it was also adopted by aging monarchs like Queen Elizabeth and King Philip II of Spain. King Philip had an invalid’s adjustable armchair constructed specifically for his comfort, with quilted padding, a footrest, and ratchet bars with teeth to adjust his posture from upright to fully reclining. This is the sort of throne that Robert Baratheon might have commissioned had he survived that fateful boar hunt in the first season.

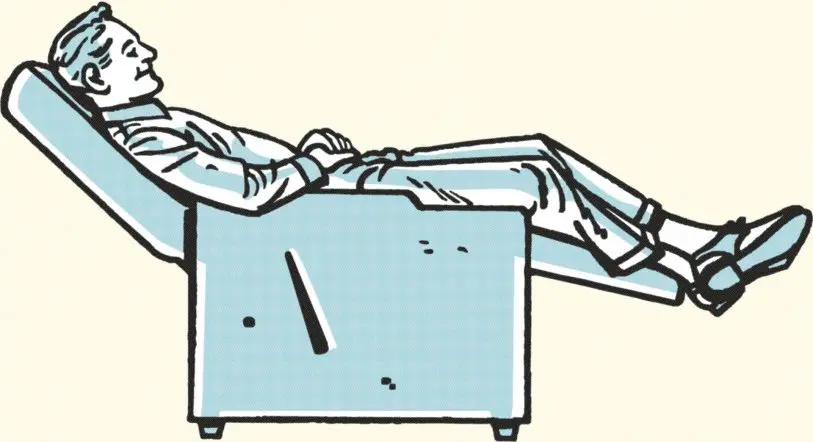

These mechanical innovations made it into mass production during the industrial revolution to boost worker productivity. The best-known manufacturer marketed its products under the appropriately named “Do/More Health Chair.” Out of these inventions emerged arguably the most profitable piece of furniture in history, the La-Z-Boy recliner. Introduced in 1961, the Reclina-Rocker combined the most popular forms of motion-adjusted comfort with a fluid mechanism covered by 40 separate patents. The La-Z-Boy recliner quickly became the ultimate symbol of domestic comfort, success, and privilege for the stereotypical middle-class American male breadwinner. At its height, La-Z-Boy recliners were said to be in more than 25% of U.S. households and offered in 50,000 combinations of style and fabric.

The unlikely explosion of mechanical seating carries a hallmark of user-friendly design: Some of the most successful and innovative products emerge not from focusing on average people, but by designing for specialized needs (not unlike Bran Stark’s). We only need to look to Pellegrino Turri and the typewriter, Alexander Graham Bell with the telephone, and Vint Cerf and email for inventions that started with the needs of the disabled in mind but eventually helped all of us. Or consider the now-ubiquitous Aeron chair, the closest thing to a modern throne in the contemporary workplace. The Aeron didn’t emerge from a study on workplace comfort and usability. Rather, it originated from a research project into breathable mesh structures that would prevent bedsores among the elderly.

While seating may seem too basic to even refer to as a “technology,” it can take many different forms in the hands of a designer, from throne to domestic appliance to rehabilitative device. But much of this history is hidden. When we focus only on the role of user friendly design in contemporary technology, we ignore centuries of transformative ideas that continue to shape the way we live, work, and play today.

Robert Fabricant has been working at the forefront of user-friendly design for more than 25 years for organizations like Microsoft and Frog. He is the cofounder of Dalberg Design, a unique practice focused on social impact with design teams in London, Mumbai, Nairobi, and New York, and a finalist for Fast Company’s World-Changing Company of the Year. User Friendly: How the Hidden Rules of Design Shape the Way We Live, Work, and Play by Cliff Kuang with Robert Fabricant (FSG) will be released in November of this year. You can follow him on Twitter.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.