Packaging is an ancient practice. Humans have been improvising containers for holding and transporting things for millennia, from baked clay vases to tanned leather satchels to sawed and nailed wooden crates.

But it wasn’t until the 1800s that cardboard boxes as we know them came about. Lightweight and disposable, they were first used in France in the 1840s to transport the delicate Bombyx mori moth to silk manufacturers–likely because it kept moths alive better than less breathable boxes. Around this time, several entrepreneurs began pushing the boundaries of paper. A top hat manufacturer realized he could pleat paper for the inner lining of his hats in 1856 and patented the process. “Corrugating” paper in such a way built up the bulk, tensile strength, and shock absorption of paper.

By 1890 we had the corrugated cardboard box as we know it. And as a result, 20th-century shipping became about paper, not wood, as it had been previously. Go to any big retail store, and you’ll see countless dyed paper and plastic packages on the shelves. But laying behind them, in the stock room? The corrugated boxes that shipped them there. And nowadays, thanks to Amazon Prime and the rise of fast shipping, these brown boxes are piling up on our doorsteps.

“What you have is a situation where packaging was always very practical. The corrugated box has a fairly unceremonious life where it’s meant to get from point A to B,” says Jesse Genet, founder of the packaging supply chain firm Lumi. “It’s such a recent development that the corrugated box is coming directly to someone’s home and has an opportunity to make an impression on someone.”

Corrugated boxes, once the realm of stockrooms and UPS trucks, are now branding tools. And they are especially important, given that few of us ever interact with a brand in real life now. In the era of e-commerce, boxes are the new storefront. But it’s not just direct-to-consumer startups that are seizing the opportunity. Now giants like Target and Amazon are rethinking the humble cardboard box, too. And they’re doing it in a very brand-consistent way. For Target, it’s all about sparking joy. For Amazon, it’s all about efficiency. In each case, they are burnishing their brand through packaging.

E-commerce sites use restrained glitz and glam

Lumi serves some of the biggest direct-to-consumer brands in the world, including Casper and Brandless. In some cases, it makes sense for the brand to embrace a basic cardboard aesthetic. Brandless is a perfect example of that, with a simple brown box with “Brandless” stamped on the side. The implication is that you’re saving money by not having lots of expensive, colorful ink in your packaging.

For the most part, if you’ve seen something on your Instagram feed–like organic shampoo or a meal delivery service–chances are good it came in a roll end tuck box. It’s basically a shoe box that opens easily from the front. Because you line up the box a certain way before you open it, that allows retailers to arrange your goods in a premium-feeling reveal, like a gift basket.

From there, the possibilities are only limited by budget. If a company wants to ditch the cardboard look, it might use a flood coat–basically coating the corrugate box in a bright dyed wrapper. Another company might add in cloth bags. It’s even possible to get custom cornstarch packing peanuts in the shape of a logo.

But millennials are mindful of wasteful packaging, and budget is a major concern for e-commerce sites, which is why you still see so much plain old cardboard in the mix. In fact, Genet founded Lumi to help other businesses manufacture their packaging only after she raised over $250,000 on a Kickstarter campaign for a line of light-sensitive ink kits, and saw firsthand that it would cost $90,000 to pack and ship products. “I had a line item in the budget, but no realistic understanding of what that stuff would cost,” she says. Cardboard packaging with a little something extra is the default for e-com companies that want to impress customers without breaking the bank.

Target chases experience

Target has a similar approach. To better compete with online competition from Amazon and every other online retailer, Target announced the introduction of free two-day shipping in 2018. For many shoppers, that changed their relationship to Target. Whereas they once defined Target as a place to grab some Starbucks and peruse nominally priced cookware, they now saw it as cardboard arriving on their doorstep.

Earlier this year, I got a pleasant surprise. Pulling in a Target box from my porch, I noticed it had a delivery van printed on the side with the Target dog Bullseye driving it. Minutes later my son was sliding the box around the carpet. Thanks to a bit of printing, the box was no longer a box. It was a car.

Weeks later, Khoi Vinh, a designer at Adobe, shared a similar experience on Twitter.

https://twitter.com/khoi/status/1107671002497105922

Of course, we both reacted precisely how Target wanted–with the shopper’s delight that is a marketer’s holy grail. “The inspiration itself really came from our CEO Brian Cornell, it was a question he asked. ‘We have these shipping boxes that show up in the homes of millions of our guests–could that be another way we represent our purpose . . . in a new way?'” recounts Todd Waterbury, chief creative officer at Target.

Working with his team, Waterbury looked at Target’s corrugated box designs and realized that while the boxes came in all shapes and sizes, a mere three box models accounted for 70% of all shipments the company was making. That meant if they did something to just those most popular boxes, they could delight most of their customers with relative ease.

“Rather than doing what many other people do in this space, which is identify a pattern or the wordmark of a company and put it all over, we took a different path,” says Waterbury, no doubt talking about direct-to-consumer brand boxes. “[We asked] what if every one of those boxes could be a different story, and every time you get something you might . . . see Bullseye the dog in a different part of the story?”

Each box is like a single-serve narrative scene. The largest box is a small house, with the Bullseye sitting on a couch, listening to tunes. The medium box is the aforementioned delivery truck. And the smallest features Bullseye popping his head, ironically, out of a box.

“We think a lot about the power of design, and this is an example of how we’re bringing the power of design into something that is as everyday as a cardboard box,” says Waterbury. “But we’ve elevated it in a way that I think creates a smile and sense of playfulness.” It’s all very Target.

And as Genet points out, that’s a pretty good return on investment for the retailer, since “the cost of ink is definitely negligible,” she says.

Amazon challenges scale

For Amazon, which has 100 million Prime customers who can order millions of items in any given day, packaging is more a science than an art.

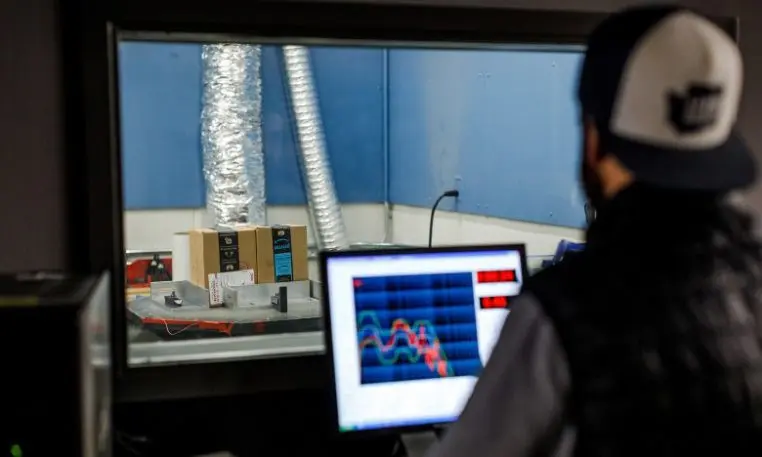

At the core of Amazon’s cardboard box design is what its packaging engineers have dubbed “the matrix.” It’s a machine learning algorithm that is constantly taking in data about new products–analyzing fragility, weight, and size–and determining the best corrugated box (or more recently, paper mailer) to send them in. The most important point is that to Amazon, the box is not a stagnant design. Every single time a person receives something broken and reports it, that data point is fed into the matrix. Even though Amazon’s website can be bad at showing it, consumer feedback is heard and accounted for. And so if a certain tea set is found to arrive broken more often than not, Amazon’s AI will assign it a new box in the future, automatically and without the need for human oversight.

[Image: Jordan Stead/Amazon]

At any moment, Amazon’s matrix data shows 10,000 different corrugated boxes, of various sizes, thicknesses, and weights, that could be in circulation. For the practicality of producing and packing boxes, Amazon keeps about 100 boxes in rotation at any time. As the products Amazon carries change enough to mandate a shift in strategy, it will swap a few boxes into rotation and a few boxes out.

Amazon cares about customer experience, but more through a lens of reducing frustration and environmental impact than sparking joy. They test if boxes can be squished down with your foot and tossed into a recycling bin. They’ve been working to reduce those absurd “box in a box” moments–like pulling a 55-inch TV box out of an even bigger Amazon box. Amazon also constantly refines its ubiquitous paper-based tape–which like its boxes, is recyclable. (Yes, in most cities you’re supposed to rip off plastic tape before you throw a cardboard box into recycling!)

It all adds up for Amazon. Using the matrix to reduce packaging waste led Amazon to save shipping 305 million boxes in 2017 alone. Of course, all of this is mostly an invisible process to the consumer. (Though I, for one, can’t recall the last time that Amazon shipped me a tiny item in a massive box, either–a practice that was once commonplace.) Amazon needs to be thought of as hyper-efficient and fast. These boxes may not be stylish, but they support what Amazon wants to say about its brand.

The bottom line: The cardboard box as we know it has changed more in the past 10 years than in the previous 100. And as it becomes the face of companies and products–with retail decreasingly about what sells in a store and increasingly about what arrives at your door–it could have a ripple effect across consumer goods. “Why does detergent come in a bulky plastic bottle with a big sticker? Because that’s what caught your eye on the shelf. The bottle is squat and wide so you see and grab it,” says Genet. “It doesn’t need to look like that anymore. Every category that was designed to sit on a shelf is going to get reimagined.”

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.