Last week, the Google sister company Sidewalk Labs unveiled a comprehensive system of urban signage designed to disclose what technology it is using to track people in public spaces. The signs are meant to be a visual representation of the privacy policies the company is developing to go along with its data collection technology. At first, the company plans to display the signage at its Toronto office, where it is testing mockups and prototypes for its planned “smart” neighborhood in the city, but it hopes other companies and cities will adopt the system as well.

Each sign features a disclosure of the otherwise-invisible technology that Sidewalk Labs is proposing to use in its 12-acre development, known as Quayside. That project has come under fire from privacy advocates; the Canadian Civil Liberties Association is now suing all three tiers of Canadian government over Quayside.

With the new signage, Sidewalk’s design team is attempting to confront a major challenge facing both companies and cities collecting data in public spaces–and the concerns of citizens in those spaces who care about their privacy. Yet, even if Sidewalk and other smart city companies disclose their technology to people, there is still no underlying framework through which people can opt out of being tracked in public space, short of avoiding public space altogether.

“While this project does not address all the issues of consent around data collection, we believe it is a meaningful step forward,” says Jacqueline Lu, the associate director for the public realm at Sidewalk Labs, who lead the project. “The project aims to address the issue of meaningful notice and transparency, and aims to give agency to people and create awareness around the kinds of technology in the public realm.”

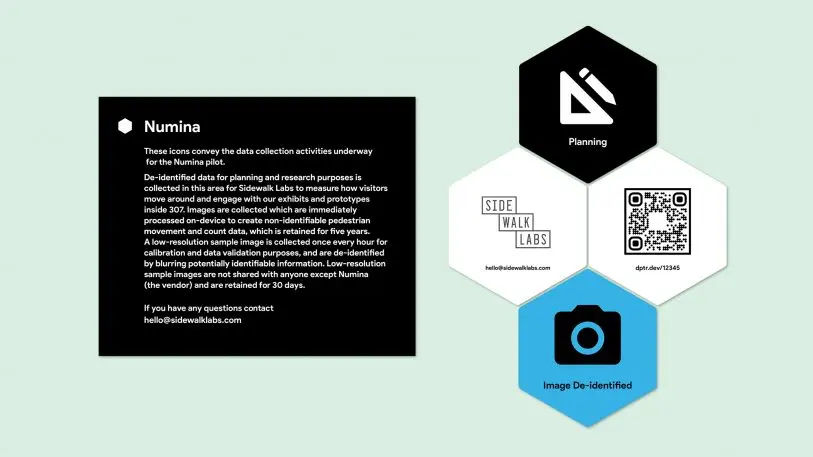

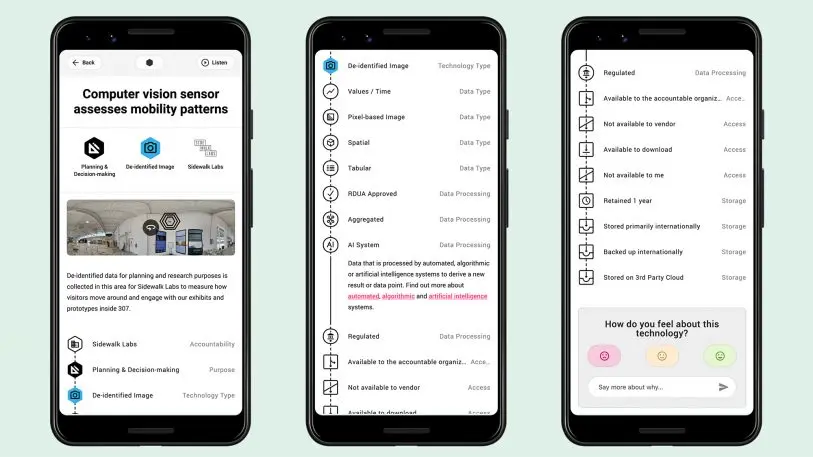

The color-coded signs are hexagonal, because the shape isn’t usually used in public space and lends itself to multiple hexagons being combined to express more complex ideas. The system is based around four types of signs, with the idea that a single technology would be disclosed using a set of three or four signs that explain what the technology is, its purpose, the company behind it, and whether it’s tracking you individually or not. Black signs tell people what the technology is being used for, like enforcement, mobility, or planning. Blue signs inform people what exactly the technology is sensing (like sound, video, or light) and disclose that all data will be de-identified. Yellow signs are similar to the blue ones, showing the type of sensor, but they indicate that people will be individually identifiable. Finally, a white sign complements the other three by sharing the logo of the entity that has control over the data, like Sidewalk Labs.

The signs also include a QR code and URL that people can use to learn more about how the technology works. The digital interface, which provides this information in a series of tiles, provides information about where and how long it is stored, whether third parties have access to it, if it is publicly downloadable, and more.

Per Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), companies collecting personally identifiable data are required to disclose it, and this signage system is designed to comply with this law. But it does more than that, the company says: “Because the icon set is used for all technologies, not just the ones that collect personal information, this project goes above and beyond PIPEDA’s requirements, in the same way that our proposals for urban data go above and beyond current legal requirements by focusing on data that is not only about people but can affect them,” says Chelsey Colbert, a legal associate at Sidewalk Labs.

For Patrick Keenan, a principal designer at Sidewalk Labs who worked on the signage, this is “a way to make legal language more like visual language,” he says. They’re akin to the disclosures you might see for a CCTV camera, but Keenan wants this system to be more flexible and open to feedback. It was also designed to be able to accommodate technology that isn’t feasible yet; one sample sign warns passersby of air sensors that can identify them personally, something that’s not currently possible. But it may be one day, and Keenan wants the signage to be able to accommodate future technologies that we can’t imagine right now.

However, the signage system doesn’t solve the biggest problem around technology in public space: Even if it’s disclosed, you still can’t opt out of it. Nor is there any way to indicate consent, or differentiate consent for some sensors to collect information about you, but not others.

Next, Sidewalk Labs and any other institutions that are interested will start deploying the signs in public spaces and asking for feedback from people to learn more about if the signs are doing what they were designed to do: disclose data collection in a way that’s accessible and easy to understand. Through this process, the signs will ideally be improved based on the feedback. Eventually, Lu hopes that the signage, despite the fact that it doesn’t solve the problem of consent, will become a universal standard for disclosing technology in public space.

The signs, which are still early prototypes, came out of a series of design sessions with experts in public space, technology, privacy, and visual design, including feedback from people about what kind of information was important for them to learn from a sign and what could be provided through accompanying digital interface. The materials for these design sessions are available online, with the goal that others will add their input and test the signs out. So far, an outdoor media company has committed to getting people’s feedback on whether the signage is easy to understand when it sets up digital kiosks in public space. Sidewalk Labs is already using the digital system that supports the signage in its Toronto office space, which acts like a lab for prototyping all of the company’s smart city proposals.

Ultimately, it’s important for cities to disclose what technology they’re using to monitor citizens, whether it’s security cameras or sensors to detect how many pedestrians, bikers, and drivers pass a given block. But while transparency is important, it doesn’t mean anything unless people have the option to opt out of being tracked. As the debate around controversial technologies like facial recognition heats up, companies like Sidewalk Labs will have to grapple with ways to give people a feasible way to opt out of public data collection.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.