It seems that almost every week there is a controversial story (or three) in the news about Amazon. In the past two weeks alone, there have been stories about Echo conversations being recorded and transcribed, Amazon employees protesting the company’s poor position on climate change, the company’s efforts to argue that face recognition fears aren’t “significant,” and Senator Warren questioning Amazon’s $0 federal tax bill on a $10 billion U.S. profit. A company as large as Amazon, with as broad a reach in terms of products and services, is going to be in the news—and unfortunately for them, most of these stories profile their lack of compassion, interest, or help to the world writ large, particularly to their fellow humans.

One story in the past few weeks that caught my attention was a piece in Vox that described an interview with a warehouse worker, who was complaining about the temperature of the warehouse. As Rashad Long told the publication:

“The third and fourth floors are so hot that I sweat through my shirts even when it’s freezing cold outside . . . We have asked the company to provide air conditioning, but the company told us that the robots inside cannot work in the cold weather.”

While Long and others are involved in lawsuits with the company, and are taking action to unionize, the most prominent complaints from workers seem to be focused on a single point: Amazon is claimed to be treating its workers like robots.

In a statement sent to me after this story was published, Amazon disputed this account as “absolutely untrue,” claiming that systems and teams are constantly monitoring temperatures in fulfillment centers. The company said the average temperature of the facility where Long works was 71.04 degrees Fahrenheit in mid-December.

“Amazon associates are the heart and soul of our operations,” a spokesperson said. “The safety of our employees is our top priority and the health of each employee is valued beyond productivity metrics. We are proud of our safe working conditions, open communication and industry leading benefits.”

However, from the outside, it looks like Amazon’s warehouses are enacting “Taylorism Gone Wild!” As I’ve previously written, Taylorism is an engineering management theory developed in the early part of the 20th century, and widely adopted throughout engineering and management disciplines to this day. While it was originally used to manage manufacturing processes, focusing on organization efficiency, over time, Taylorism became embedded into part of engineering and management culture. With the advent of computational tools for quantitative measurement and metrics, and the development of machine learning based on the big data developed by those metrics, organizations, Amazon among them, started to transition through a period of what I refer to as “extreme data analysis,” whereby anything and anyone that can be measured, is.

This is a problem. Using counting, metrics, and implementation of outcomes from extreme data analysis to inform policies for humans is a threat to our well-being, and results in the stories we are hearing about in the warehouse, and in other areas of our lives, where humans are too often forfeiting their agency to algorithms and machines.

In a 2013 paper I wrote with Michael D. Fischer, we explored the idea that processes were a form of surveillance in organizations, particularly focusing on the notion that when the management in organizations dictates processes that don’t work particularly well for the employees, the employees take the opportunity to develop work-arounds, or “covert agency.” Human agency is our ability to make choices from the options available to us at any given time. The range of what is possible as an option changes over time, but as humans, we have a choice. Agency is how we cooperate. We forfeit a bit of our free choice, someone else does too, and we both can reach a cooperative compromise.

Every time we use a computer, or any computationally based device, we forfeit agency. We do this by sitting or standing to use a keyboard, by typing, clicking, scrolling, checking boxes, pulling down menus, and filling in data in a way that the machine can understand. If we don’t do it the way the machine is designed to process it, we yield our agency, over and over again to do it in a way that it can collect the data to get us the item we want, the service we need, or the reply we hope for. Humans yield. Machines do not yield back.

When human agency is pitted against automation that is difficult to control, there are problems, and in extreme cases, these problems can be fatal. Such a problem has been cited amid investigations into the crashes of two Boeing 737 Max airplanes, which have focused on the pilots’ interactions with an automated system that was designed to prevent a stall. As the world continues to automate things, processes, and services, humans are put in positions where we must constantly adapt, since at the moment, automation cannot, and does not, cooperate with us outside of its pre-programmed repertoire. Thus, in many instances we must do the yielding of our agency and our choices, to the algorithms or robots, to reach the cooperative outcomes we require.

Over time, humans have evolved to trade and barter in a cooperative method, exchanging resources to acquire what we need to survive. We do this through work. In today’s market, if we are seeking a new job, we must use a computer to apply for a position advertised on a website. We must forfeit our agency to use the computer (we can no longer call anyone), where we then further yield to software that isn’t necessarily designed to handle the record of our particular lived experience. Once we’ve done our best with the forms, we push a button and hope for a reply. Algorithms on the back end, informed by management and developers, then “sort us,” turning us into data points that are then graded and statistically processed.

Only if we make it through the filters, does an automated response send us email (that we cannot reply to) to inform us of the outcome. If it is positive for us, eventually a human will contact us, requiring us to use an automated method to schedule a time for a call, which will utilize scripts/processes/narrative guidelines, that again ask us to yield our agency—even in a conversation with another human, where there is usually more flexibility. It’s exhausting.

The human costs of “frugality”

After the Amazon warehouse workers have yielded agency to get through the hiring process and are hired, they, too, are required to yield agency in their jobs. While office workers yield to algorithmic partners in the form of software or business processes, warehouse workers yield their agency by shifting their schedules, and working with robot partners instead of, or alongside, algorithmic partners in the form of software. The survival stakes are much higher for taking agency in a warehouse by not cooperating with a robot than they are by not cooperating with software at an office job.

In some warehouses and industrial settings, workers must yield to robots because robots are fast, made of metal, and could injure or kill them. In this way, a worker maneuvering around robots has less agency with regard to their body at work than those in the offices who are making the decisions about how those workers will work.

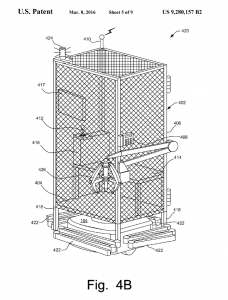

One solution Amazon proposed in 2013 was Patent U.S. 9,280,157 B2, granted in 2016. This patent was described as a “human transport device” for a warehouse, consisting of a human cage. A cage is stark symbolism. While the idea was to protect human workers from robots, it has not been perceived in the way it was likely intended. In the extreme, a cage yet again implies that humans will yield their agency to the robots, appearing to give some truth to the warehouse workers’ initial complaints that robots are given preferential treatment in the Amazon workplace.

Amazon has insisted that it doesn’t intend to implement the idea. “Sometimes even bad ideas get submitted for patents,” a company spokesperson told me after this story was published. “This was never used and we have no plans for usage. We developed a far better solution which is a small vest associates can wear that cause all robotic drive units in their proximity to stop moving.”

Whether it’s a cage or an automated vest, however, these safety interventions raise the question of whether a facility like an Amazon fulfillment center could be designed to not require humans to make these boundary sacrifices—yet still be gainfully employed.

At its core, Taylorism isn’t necessarily about efficiency for efficiency’s sake, it is about thrift of time and, by association, of money. Among Amazon’s self-described “Leadership Principles” is “Frugality,” and it is this one aspect that seems to have overrun their other ideals, for “accomplishing more with less” seems to be the overarching principle in the way the company interacts with everything, and how that interaction impacts their employees and their customers worldwide.

If a company is practicing this Taylorism throughout its culture, humans are going to make decisions about how other humans should work or interact with systems in ways that are going to be in the interest of the metrics that they are serving. If Amazon rewards frugality in management, and is collecting data on how management manages (they do), then management is going to do what it can to maximize forms of automation in order to stay relevant in the organization.

This particular principle, in tandem with Taylorism, creates the perfect environment for data mining and analysis to run amok, and for processes that impact real people’s lives to be ignored. Those in offices don’t see those in warehouses, and can’t realize that their customer service or supply chain performance metrics bear a human, and a humane cost. In an extreme version of what happens at so many companies, profits are linked to nested metrics within the stakeholder chain. Amazon’s $10 billion profit in part comes from millions of tiny Taylorism-influenced “frugal” decisions, each borne by the cost of humans forfeiting their (or others) dignity and agency.

Taylorism was designed and implemented in a time when manufacturing was mechanical, and while some machines could work faster than humans, most of the processes that impacted their work were analog, and at the pace of human processing. The Amazon warehouse worker is at the end of the line of the frugality Taylorism decision tree, and is subjected to being judged against algorithmic processes that control data and machines faster than many humans can process information, much less physically act upon it. These workers are outpaced, by a degree that is unimaginable, yet bound by a corporate mechanism that demands ever more that they and, more critically, the chain above them “accomplish more with less.”

Related: To really protect our privacy, let’s put some numbers on it

Eventually, even with a desire to “accomplish more with less,” there becomes a surplus of “less,” requiring humans to take up the ‘slack,’ creating the “more,” by stretching our own internal reserves. If every process is eventually automated and restricts human agency, while simultaneously requiring our servitude to function, we will be pinned to the wall with no choices, nothing left to give, and no alternatives for coping with it.

S. A. Applin, PhD, is an anthropologist whose research explores the domains of human agency, algorithms, AI, and automation in the context of social systems and sociability. You can find more at @anthropunk and PoSR.org.

This story has been updated with responses from an Amazon spokesperson.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.