In March, with swimsuit season just around the corner, the 10-year-old fashion label Reformation dropped a new line of bikinis and one-piece bathing suits. But the collection came with a caveat. On Reformation’s website and in an email to customers, the brand announced: “These swimsuits are not sustainable enough.”

This was an odd thing to hear from a fashion brand. At a time when climate change and plastic pollution are on many consumers’ minds, fashion labels have been loudly advertising how eco-friendly their clothes are, rather than where they fall short. Earlier this year, when Madewell launched its eco-friendly swimwear collection, Second Wave, the product descriptions noted that the suits had a “built-in feel-good factor,” since each was made with eight water bottles. Startup Ookioh advertises on its website and social media accounts that it is made with “100% regenerated materials.” These are just a few of the dozens of swimwear brands highlighting their sustainability chops.

And yet here was Reformation, highlighting the limits of its own sustainability efforts. For one thing, the suits are not biodegradable. They also shed tiny pieces of plastic called microfibers when you wash them. These particles end up in the ocean, where they’re swallowed by sea animals, before ending up in our food chain.

These problems are not exclusive to Reformation: They face all swimwear brands. But Reformation wanted to underscore these issues, rather than hide them. It’s a clever way to get the customer’s attention. It also serves to draw attention to how complex it is to be a truly sustainable fashion brand. “We’re trying to engage our customers in the messiness,” says Kathleen Talbot, Reformation’s director of sustainability. “The fact is that there are trade-offs. We’re trying to be as innovative as possible, but we want to be really honest about the limitations of existing technologies and fibers.”

The Problem With Swimsuits

So why does swimwear present such a challenge when it comes to sustainability? It comes down to one thing: plastic. Synthetic fabrics–like nylon, polyester, and spandex–are perfectly suited for swimwear because they wick moisture and stretch across the body, reducing friction in the water. They are also inexpensive to make, as well as versatile, so the fashion industry relies on them heavily, not just for swimwear, but also activewear, outerwear, and cheap fast-fashion garments. An estimated 65 million tons of these plastic-based materials are generated every year.

This is a problem because plastic is not biodegradable, so it never decomposes. Instead, it sits in landfills or oceans forever, adding to the estimated 8 billion tons of plastic that already exist on the planet. There’s no good way to get rid of this plastic. Some countries have resorted to burning it, which creates carbon emissions, since plastic is made from fossil fuels. In countries without good waste management systems, plastic-based fibers sometimes end up in the oceans, where sea animals can mistake them for food, causing them to choke.

Talbot says that Reformation tries to avoid using synthetic fibers in its clothing. Ninety-five percent of its garments are made using natural, biodegradable fabrics, like organic cotton and viscose, which comes from tree pulp. But there isn’t currently a biodegradable material that has all the performance qualities necessary for a swimsuit. As a result, eco-friendly brands are relying on the next best alternative: recycled plastic. There’s a growing list of swimwear brands that use recycled plastic, rather than virgin plastic, to make products. That includes luxury brands like Mara Hoffman, as well as more affordable pieces from startups like Outdoor Voices, Koru Swimwear, Galamar, and Vitamin A.

The Brave New World of Recycled Plastics

But recycled plastic has its limits. For one, large companies simply aren’t set up to use it. That’s why you generally see smaller startups creating swimwear out of recycled materials. Reshma Chamberlin and Lori Coulter, who launched the swimwear startup Summersalt two years ago, built their entire supply chain using nylon made from fishing nets and industrial carpets. Reformation, for its part, only began creating swimsuits three years ago, and was able to use Econyl, a nylon created from recycled plastic, including industrial plastic diverted from landfills and oceans.

But for Athleta, a large company owned by Gap, Inc., it’s a much more challenging proposition to switch over to recycled materials, partly because its supply chain is spread out around the world. It took three years for Athleta to develop H2Eco, a proprietary fabric made from recycled nylon. Nancy Green, Athleta’s CEO, says that it required significant testing to create a material that was just effective and also as affordable as the virgin materials the brand was previously using. But then, the challenge was to ensure that Athleta’s partner factories could access these fabrics and had the correct cutting and sewing equipment to turn them into swimsuits. “Not all manufacturers have the capability to make these suits,” Greens says. “So it takes time to find factories that are equipped to work with these fabrics.”

This year, Athleta announced that 85% of its swimwear is made from recycled materials, and it is working to get to 100%. Even though it’s a slow process, given the size of its operation, the upside is that the impact is also greater relative to smaller startups that produce less inventory. By using H2Eco, Athleta has managed to divert 72,264 kilograms of waste from landfills, which is the equivalent in weight to 2.4 humpback whales.

Of course, it’s important to remember that recycled plastic is not–on its own–a perfect solution. When the customer is done with it, it is likely to end up in the trash, since there are currently few facilities that recycle synthetic materials. That means the suit will be landfilled, incinerated, or it will end up in the ocean after a few summers.

But this is the reality: The quest for sustainability is full of trade-offs. Take Summersalt. From the start, the brand has relied on recycled nylon for its swimsuits. But the founders also wanted to think about sustainability from a more holistic perspective, including considering how durable the suits are. After all, swimsuits need to survive many elements: the sun, heat, salt water, and chlorine. “The longer the customer is able to use the swimsuit, the longer it stays out of a landfill,” Coulter points out.

This led the founders to reckon with a new trade-off. They wanted to incorporate a fiber called Xtra Life Lycra into the suits to help them keep their shape longer as well as resist degradation from chlorinated water, heat, and sunscreen. This would allow the suits to last up to 10 times longer than unprotected fabrics. The downside, though, is that this Lycra is made from virgin plastic.

In the end, the founders decided to include the Lycra because it would allow them to extend the life of the product, so the customer could wear it for a long time before throwing it out. But it wasn’t an easy decision. “We’re very upfront about the fact that we’re not perfect, but we’re constantly making incremental shifts to make our products more eco-friendly,” says Chamberlain. “But we’re finding that this is a tricky business, and it’s hard for every decision you make to be 100% sustainable.”

In The Hands of The Customer

About a decade ago, scientists discovered something alarming: When we wash synthetic materials, minuscule pieces of plastic are released into the water, which eventually find their way into the ocean. Biologists have found that that traces of microplastics are found inside fish, which means that they have now entered the human food chain. While the study of microplastics is still in its infancy, early research has shown that these materials are taxing our livers and kidneys. “Fashion is not the only industry contributing to this problem,” says Reformation’s Talbot. “But synthetic apparel is definitely contributing to it.”

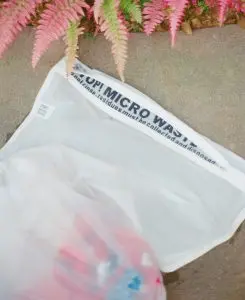

Brands can’t control what happens to a product once it’s in the hands of the consumer. But with its swimwear campaign, Reformation is trying to raise awareness about the problem of microplastics. On its website, Reformation offers customers tips to reduce the shed of microplastic, including gently washing synthetic garments by hand in cold water (which has been shown to release fewer particles than the rigorous cycles of a washing machine). The company also sells a product called Guppyfriend, a bag that captures microfibers when you hand- or machine-wash your synthetic clothes, so that these particles don’t end up in waterways.

But Talbot admits that this is not an adequate solution. After all, you still need to somehow dispose of the microplastics inside the Guppyfriend bag. This involves pulling them out and putting them in the trash–but these tiny particles may end up in the waterways anyway, since they are swept away by rainwaters. Ultimately, Talbot believes that the only way to truly deal with the problem is to install filters on washing machines or in the sewer system to capture the microplastics before the end up in the water–and then use an industrial machine to suck up these plastic particles and recycle them. None of which is terribly realistic for an average consumer. Talbot is also actively looking for materials that simply don’t shed. “Nothing is commercially available yet or at scale, but it might be possible to treat the fabrics differently in the fiber and fabric finishing process to avoid this issue,” she says. “That’s definitely going to be part of the solution.”

Many swimwear brands that advertise their sustainable fabrics don’t have a good solution for helping customers recycle their swimsuits. Athleta, for instance, says it is actively working on an initiative that will collect old garments and recycle them, but this is several years off.

At Reformation, Talbot wants to give customers different ways to make products more circular. Customers can send wearable products to the online consignment store Thredup and receive credit to spend at Reformation. And they can also print out a free shipping label to send old products back to Reformation, where they will be sorted and recycled appropriately.

While we have the technology to recycle fabrics made of a single fiber, like cashmere or cotton, it’s much harder to break down synthetics, which tend to be blends of different fibers. Currently, the best way to prevent synthetics from ending up in a landfill is to send them to a recycling facility that will chop the fabrics into little pieces, which can be used for other products, like housing insulation and the stuffing for throw pillows.

Ultimately, Talbot is gunning for a time when it will be possible to recycle plastic-based fibers. Scientists are currently developing machinery that will separate different fibers in a blend–pulling the nylon apart from the cotton, for instance–and turn them back into new fibers, which can be used for new clothes. This is much like the way we currently recycle paper into new paper, or plastic bottles into new bottles, in a perfectly circular system. Once we are able to scale this technology, it could transform the entire fashion industry. In theory, it would mean that fashion brands would never need to rely on raw materials ever again.

While synthetic fabrics are currently a scourge on the planet, collecting in landfills and the oceans, Talbot envisions a world in which we stopped making plastic altogether, and instead constantly recycle the plastic we already have. “No one really has the silver-bullet solution for circularity,” says Talbot. “But one of the things that is promising about synthetics is that they can be recycled infinitely.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.