“My freshman and sophomore year I was the only student in the whole school with a headscarf,” says Ayah Abdul, a senior at a performing arts high school in New York City. “I’m still the only student in my grade who wears one, which is crazy.”

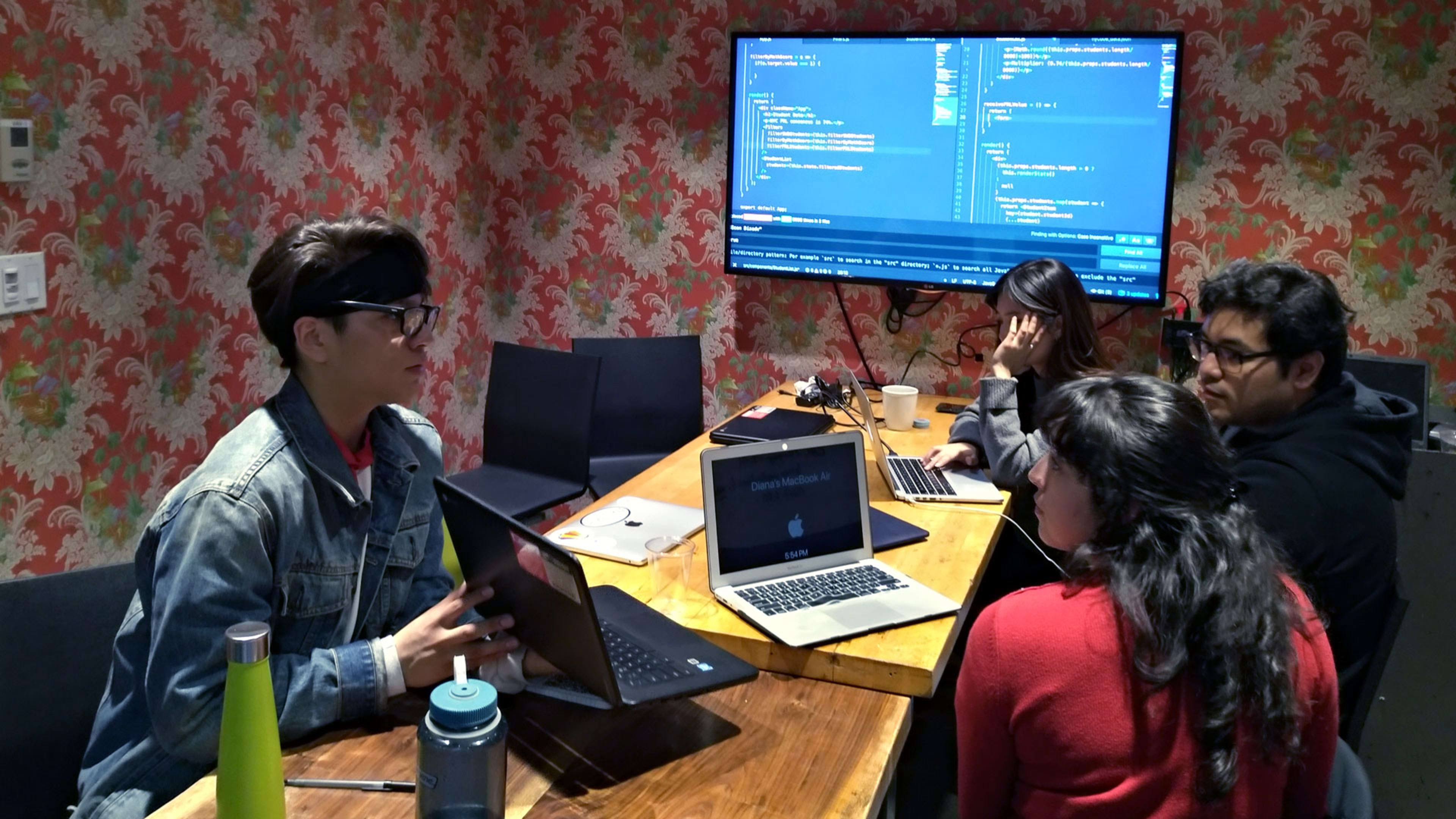

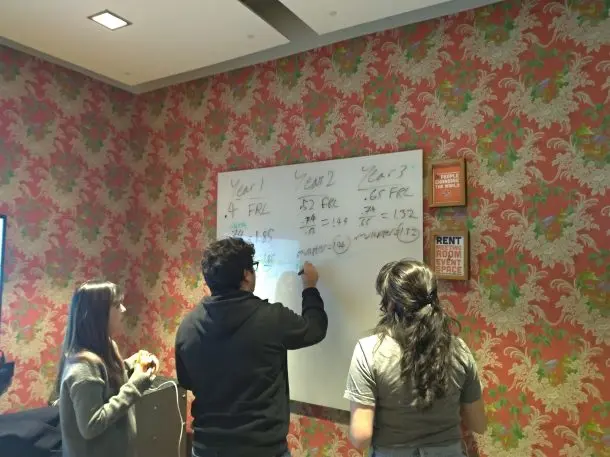

Students like Abdul, who are part of the youth-led organization IntegrateNYC, are advocating for more racial diversity in New York City high schools, which are some of the least diverse in the nation. To make that happen, they are pushing for a key piece of the high school admissions process to be fundamentally changed. The city’s students are currently placed with schools through a matchmaking algorithm based on school and student preferences. At an all-day hackathon last week in Manhattan, Abdul joined other students and adult collaborators to create a prototype of a new algorithm that would take into account the race of students so that high schools might better reflect the diversity of the city.

The debate about racial diversity in New York City public schools has garnered newfound attention in the past year, reaching a fever pitch after a New York Times headline last month pointed out that only seven black students were offered admission for 895 spots at Stuyvesant High School, the city’s most selective public school. Much of the debate has focused on so-called “specialized” high schools within New York like Stuyvesant, which base admissions on a unique standardized test.

But the lack of racial diversity extends far beyond just those eight specialized high schools to the rest of the the city’s nearly 500 public high schools. A 2014 study by the Civil Rights Project at the University of California found that New York has one of the most segregated school systems in the country, especially for black students. Many of the most desirable, highest-performing schools have a gross disparity between the racial breakdown of who applies versus who eventually attends those schools.

Data acquired from the Department of Education by IntegrateNYC through a freedom of information request and provided to Fast Company bleakly demonstrates this point. For instance, while white students accounted for one quarter of students who applied in 2017 to Beacon High School, 42% of that Fall’s freshman class was white. At Eleanor Roosevelt High School, 16% of applicants that year were black, yet less than 1% of admitted students were black.

Part of the problem is that the education children receive from kindergarten to eighth grade is not equal. Students who live in more affluent, largely white neighborhoods have better middle schools, which better prepare students for high school entrance exams. Students from wealthier families are also more likely to be able to afford private test prep for their students. But the city’s current admissions process does nothing to correct this.

How NYC places high school students

Students rank-pick up to 12 schools, in order of preference. Schools are then allowed to set up screens to filter out students that do not meet their requirements. Most screens include academic performance and standardized test scores, but others judge a portfolio of writing or art, or may include an interview, audition, or some combination thereof. Then schools rank the students they would like to admit.

From there, a matchmaking algorithm does the rest. The New York City high school admissions process was revamped in 2004 when that algorithm, created by three economists, replaced how students were admitted to schools. The algorithm uses game theory to go through “rounds” of matchmaking, guaranteeing that no student ends up at school that is lower on their preferences than another school that would take them, given the students still available to that school. It eliminated so-called “sub-optimal” matches, and one of the creators, Alvin Roth, went on to win a Nobel Prize in economics for his work on the subject.

The problem with that algorithm, students and experts today argue, is that it fails to account for disparities along racial lines. Because students are frequently screened by test scores, in which white and Asian students consistently perform better than black and Hispanic students, it ends up reinforcing existing inequality.

“When the data going in is a product of all kinds of existing inequities, then the formulas may work perfectly but they don’t solve the inequity,” said Jesse Daniels, a professor of sociology at Hunter College. “The algorithms reproduce it, or they make it worse.”

As big data and the algorithms that make use of them have become a bigger part of our world in recent years, researchers have started to explain how these ostensibly color-blind algorithms can replicate racial disparities. Much of the focus on these algorithms has focused on criminal justice, including predictive policing and risk assessments in parole hearings, with comparably little attention on algorithms in education. But the principles are the same.

“This is a pretty consistent finding with supposedly ‘neutral’ algorithms that happens because those algorithms get created within social worlds that are, themselves, unequal,” said Daniels. “The algorithms are mathematical and computational formulas that respond to the data that is fed into them.”

A new algorithm

The solution students came up with was to create a new matchmaking algorithm that prioritizes factors highly correlated with race such as a student’s census tract, whether they receive free or reduced-price lunch, and whether English is their second language. Such an algorithm would boost disadvantaged students higher up in the matchmaking process, provided they have already passed a school’s screening process.

“There’s nothing wrong with a neutral algorithm fundamentally, but because we’re overlaying it on a system that’s predicated on racist and classist measurements of our students, it’s just replicating that kind of system,” said Yana Kamlyka, IntegrateNYC’s research director and a current undergraduate student at Cornell. “It’s essential to include equity-prioritizing elements in the process. I think it’s important that our education policies are deliberately anti-racist instead of neutral.”

The New York City Department of Education has tried in other ways to increase access to the best schools, without touching the school placement algorithm. A current policy requires that schools that screen applicants ensure that at least 20% of those who pass their screens are students with physical or learning disabilities. There is no comparable threshold in the screening process for race.

The Department of Education did not respond to questions from Fast Company about whether it would entertain altering the matchmaking algorithm or other attempts to racially integrate public high schools.

At the hackathon on Saturday, students discussed issues they see in the high school admissions process beyond just the algorithm, touching on the ways the screening out of candidates is done or how students’ interests are not adequately reflected in the admissions process. But they decided that the algorithm was the best and likely easiest piece of the admissions puzzle for the city to target.

Students are hopeful that the Department of Education will adopt an alternative algorithm they create or incorporate some of the suggestions they produce. IntergrateNYC has had success working with the city in the past, with three students affiliated with the group sitting on the School Diversity Advisory Group that Mayor Bill de Blasio created in late 2017.

Whether through the algorithm or other interventions, they intended to continue pushing the city to better integrate high schools so that educational opportunities are better distributed.

“I can’t help but notice when I go into schools that are predominately white that they have fancier buildings and a wider variety of programs, more AP classes, their libraries are bigger, they have more after-school programs,” said Brandon Alonzo, a student at a high school that is majority people of color. “My school just closed its Saturday program.”

“There’s no such thing as separate but equal.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.