Capital & Main is an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political, and social issues.

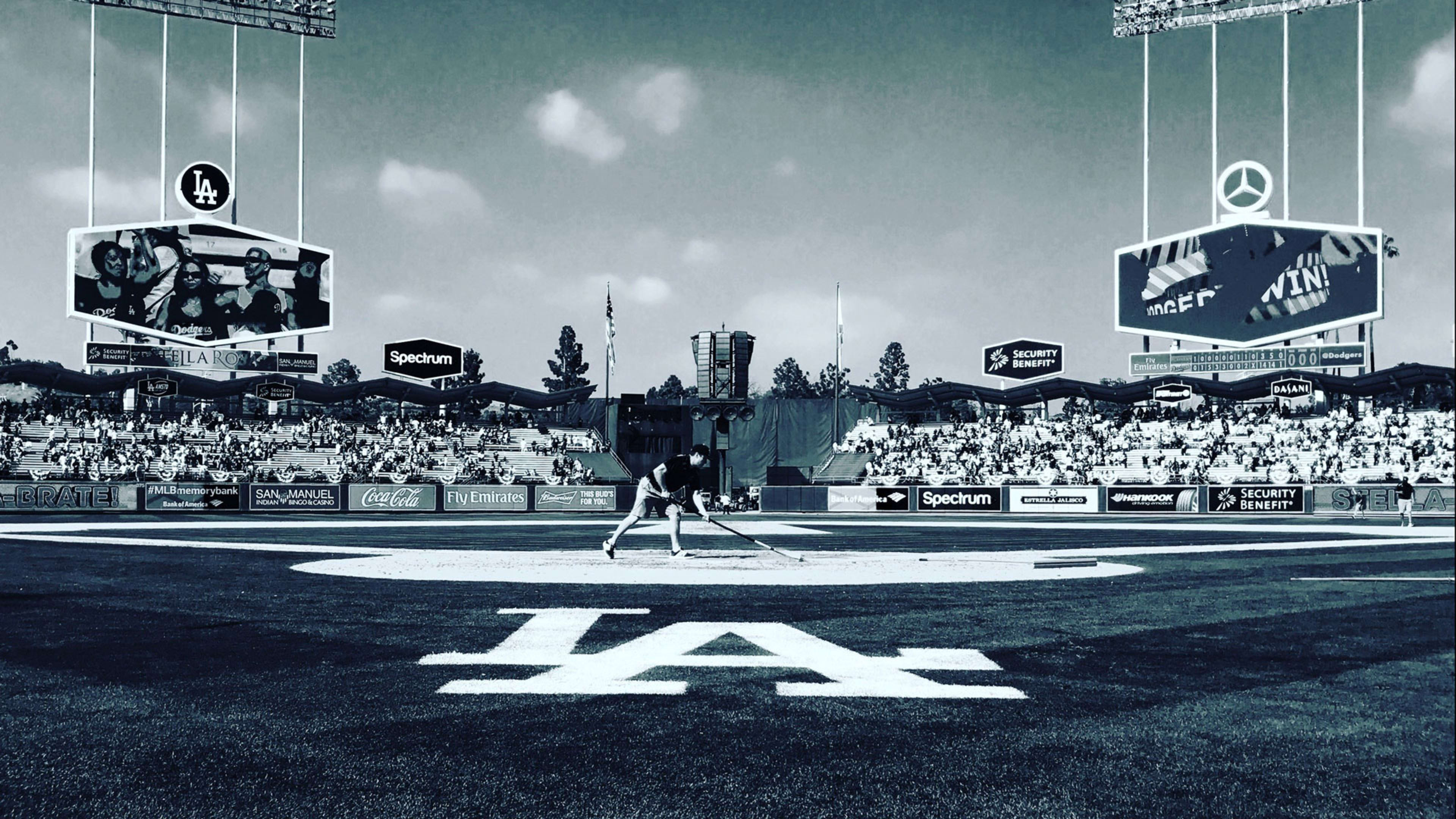

On opening day of the 2019 season, March 28, one of the most multicultural fan bases in Major League Baseball will once again fill Chavez Ravine to cheer on their Dodgers. This year, however, when their beloved Blue and White take the field, there will be a whole lot more white. That’s because the franchise that broke the color barrier with Jackie Robinson in 1947, and has been a model for diversity in baseball for decades, will field a starting team that is nearly all white.

Gone are longtime fan favorites Adrián Gonzalez and Matt Kemp. Gone is the mercurial Yasiel Puig. Culled from their 25-man opening day roster, the Dodgers starting lineup will feature only one person of color, second baseman Enrique Hernandez.

The relationship between the Dodgers and diversity has always been complicated. Chavez Ravine, the arid canyon on which Dodgers Stadium sits, was once a poor Mexican-American neighborhood. The L.A. City Council targeted the area for development in 1950–and over the following decade some residents would be forcefully removed from their homes. How much a part this played in the initial reticence of Latinos to follow the Dodgers in large numbers is up for debate, but it wasn’t until southpaw star pitcher Fernando Valenzuela burst onto the scene in 1980, sparking Fernandomania, that Latinos began embracing “Los Doyers.” Further diversification came in the 1990s with the addition of Korean hurler Chan-Ho Park and Japanese pitcher Hideo Nomo, who brought Asian fans through the turnstiles.

MLB’s demographics have shifted dramatically in the last 25 years. While the evaporation of black players in baseball has been well documented, the percentage of Latino players has risen. Every year, Dr. Richard Lapchick, director of the University of Central Florida’s Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, releases a “Racial and Gender Report Card.” Last year’s edition reported that baseball sported the highest percentage of Latino players (31.9%) and total players of color (42.5) in MLB history. But conversely, MLB also is reporting its lowest percentage of players who are black (7.7) since the studies began in 1991. (In 1991, by comparison, 18% of all players were black and 14% were Latino.)

A survey of major league clubs reveals that most teams show significant representations of players of color, especially for projected opening day starting lineups. For instance, five of nine starters on the 2019 Yankees starting lineup are minority players. The World Series Champion Boston Red Sox have seven. The National League’s Philadelphia Phillies field five of eight (the American League’s designated hitter adds a position) and the Dodgers’ NL Western Division rivals, the San Diego Padres, four of eight.

The average 2017 starting lineup was 57.5% white, 31.9% Latin, 7.7% African-American, and 1.9% Asian. By comparison, the starting lineup for the Dodgers in Game 1 of the 2017 World Series included seven white players, two Latino players (Hernandez and the Afro-Cuban Puig)–and no African-Americans or Asians.

But nearly half the team’s fans are Latino

It was only at the beginning of last year that the Dodgers had players who were born in more countries–eight–than any other MLB roster. But a series of moves over the past year has changed things.

Besides Puig, Kemp, and Gonzalez, the Dodgers last year unloaded pitcher Yu Darvish and outfielder Curtis Granderson, who were becoming free agents. During this past off season, the Dodgers chose not to re-sign Manny Machado and Edward Paredes. Then Yasmani Grandal declined his qualifying offer.

And as spring training came to a close this year, the team sent prospects Keibert Ruiz, Dennis Santana, and Yadier Alvarez back to the minors. And now, the 2019 team’s projected 25-man roster will, at most, probably have nine players of color.

It is estimated, on the other hand, that nearly half the fans coming to Dodger games are Latino. Jorge Jarrín has grown up watching the diversification of the fans up close. His father, Jaime, has been the Dodgers’ Spanish language announcer for 60 years, with Jorge teamed as broadcast partner with the elder Jarrín during the last four years.

“We’ve seen it not only grow in terms of fans who come to the stadium,” says Jarrín, “but we’ve seen it also grow in sponsors who are dedicating more and more of their dollars [because they think] the Dodgers are a good vehicle to reach that Hispanic market. And don’t forget the Dodgers are a global brand. We hear a lot from fans in Latin America and Mexico. We have people who listen to the Dodgers on a regular basis from as far south as Argentina, and, and all through the Caribbean.”

Will it impact ticket sales?

So how will this considerable segment of the team’s fan base react to the new-look Dodgers? Will the makeup of the team negatively affect ticket sales?

New York Times sports columnist Michael Powell, who has written extensively on baseball and diversity, is perplexed, like many observers, and wonders about the optics of it all.

“I mean, their manager Dave Roberts is half black and half Asian . . . so it really astonishes me,” says Powell. “Just the economics of it . . . you would think that at least they would want them to have a diverse team. It feels tone deaf.”

Having foreign-born players on a roster has been proven to have a positive economic effect, with a 2010 study by the University of Michigan finding each foreign-born player added to an MLB roster increased annual team ticket revenue by approximately $500,000.

Ironically, Jarrín says, it may actually have been economics that has led to the current Dodgers situation. “Manny Machado could have been a superstar in Los Angeles,” he says. “But he wanted the big dollars, and in terms of how the owners run their operation . . . they weren’t about to make a commitment to anyone, whether he’s Latino or Caucasian or African-American, for 10 years. Because they owe it to the organization to keep things in line and because you can’t continue to pay a luxury tax that at some point reaches almost 50% of your payroll.” (Each team is allocated a certain amount of money it can spend, while also assigned an amount of tax it will pay if it spends beyond that assigned limit. MLB instituted this to limit wealthy teams from outspending more cash-poor teams for talent.)

And, offers Jarrín, there is this rumor: “What I’ve heard people say, you know, maybe it’s Andrew Friedman–who came from Tampa Bay and that was a nearly all white team. But I really don’t believe that. Not when, when I’ve seen what has been drafted on the international market, and who they are developing.”

Friedman was signed as the Rays’ general manager in 2005 at the age of 28. In eight years Friedman transformed Tampa Bay into a winner, even reaching the World Series in 2008 for the first time in franchise history. But the Rays (as they were called until 2008) also went from being one of the most diverse teams in the league in 2005 (nearly half the 40-man year-end roster was comprised of players of color) to one of the least by the time he left in 2013 (with only a quarter players of color). Is there a reason that goes beyond coincidence or pigment? The real reason may have more to do with a color not yet mentioned: green.

Friedman became the Dodgers’ president of baseball operations in 2014 and is known for relying on analytics, which focuses on finding diamonds in the rough. Some maintain Latino players require more of an investment, and tighter purse strings mean less emphasis on developing foreign players to reduce costs.

“You have to take into consideration that the development of a Latino ballplayer takes a little bit more in times of effort and money in terms of assisting them in getting acculturated to being in the United States,” says Jarrín. “It’s quite a culture shock. But I think it’s really just a coincidence, more than anything else, that the pendulum has just swung that way.”

(The Dodgers and MLB engaged in multiple off-the-record phone calls and emails regarding this story, but both refused to comment officially.)

Jackie Robinson’s former team has no black starters

Whatever their reasons, do the Dodgers or Major League Baseball in general have a responsibility to reflect a particular fan base or society generally? One of the enduring conundrums plaguing American capitalism is the question of the relationship between legitimate business interests and social responsibility. Harry Edwards, PhD, whose studies on politics and race in sports virtually created a field study–the sociology of sports–contends that, historically, social responsibility has really only impacted business decisions when those concerns are inextricably intertwined with business interests. As an example, Edwards cites MLB’s African-American experience.

“On the opening day of MLB,” Edwards says, “every player in the League wears Number 42, Jackie Robinson’s number. The irony is that today, there are fewer than 8% African-American players in MLB, and his former team has no black starters. It is an alarming trend that now sees many teams with rosters with only one or two African-American players.”

According to Edwards, baseball’s desegregation was not some sort of moral awakening. Instead, the league was merely taking advantage of a new fan base, as it sought to draw on both the prodigious talent in the Negro Leagues and the dollars spent on the games by African-Americans. But with Dodgers’ ticket holders tilting close to 50% Latino, does Edwards think the organization has a responsibility to reflect its fanbase?

“Were teams comprised of ‘elected’ as opposed to ‘selected’ front office and player personnel, I would say, unequivocally, ‘Yes.'” But given that is not the case, Edwards says the obligation is not to decry the current situation, but rather to understand the origins and dynamics of such a situation: “Sport inevitably recapitulates society–the situation in MLB says much about what we have already become as a society and much about where we could be headed as a nation.”

As our country has become divided over political interests (to a large degree along racial lines), so too has interest in sports. For instance, a 2013 Nielsen study revealed 83% of baseball television viewers are white. “In both the case of MLB and that of the NFL–in which blacks constitute 72% of players–existing circumstances bespeak an increased trajectory of ‘silo functioning’ across American institutions,” says Edwards. “It is less and less the case that we are coming together either in or beyond the arena.”

Over the years since, Edwards says, the business model for MLB has shifted again by emphasizing the “offshoring of player personnel development” by seeking talent in Latin America. “Emblematic of this shift was the development of MLB player development academies in places such as the Dominican Republic, Panama and Mexico,” he says. “As a result, today 40% of players overall in the MLB system (including those in the minors and in academies) are Latin American.”

The Dodgers were the first team to build an academy in the talent-rich Dominican Republic (Campo Las Palmas in 1987), and they still have an extensive scouting team in Latin America, so it becomes even more pronounced that they have so few Latin players.

Broadcaster Jorge Jarrín, though, sees the current Dodgers lineup as a temporary glitch, with a brown wave gathering on the horizon.

“In terms of players in the minor leagues who are coming up, you have a number of Latino ballplayers that, when they break in, you might all of a sudden see the makeup of the team shift again.”

Metrics suggest this is a distinct possibility. Of the top 30 Dodgers prospects listed on mlb.com, 15 of them are minorities. However, until some of these players of color make it to the big leagues and into the starting lineup, it remains to be seen whether the new-look 2019 Dodgers will end up making many of their fans simply blue.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.