In 2029, there’s a good chance you’ll be living in a Google, an Amazon, or an Apple home–you and all of your data, biometric and otherwise. Adding smart devices to your house may have started as a way to make your life and your energy use a little more efficient. But 10 years from now, it may blossom into a full-scale operating system that has automated your life in ways you don’t fully understand.

What might that look like? “The microwave decides you should be on a diet and won’t let you eat popcorn,” says Amy Webb, a professor of strategic foresight at the NYU Stern School of Business and the founder of the consulting firm Future Today Institute. “The washer decides you can get another day out of those jeans. Your garage decides you should walk to work.”

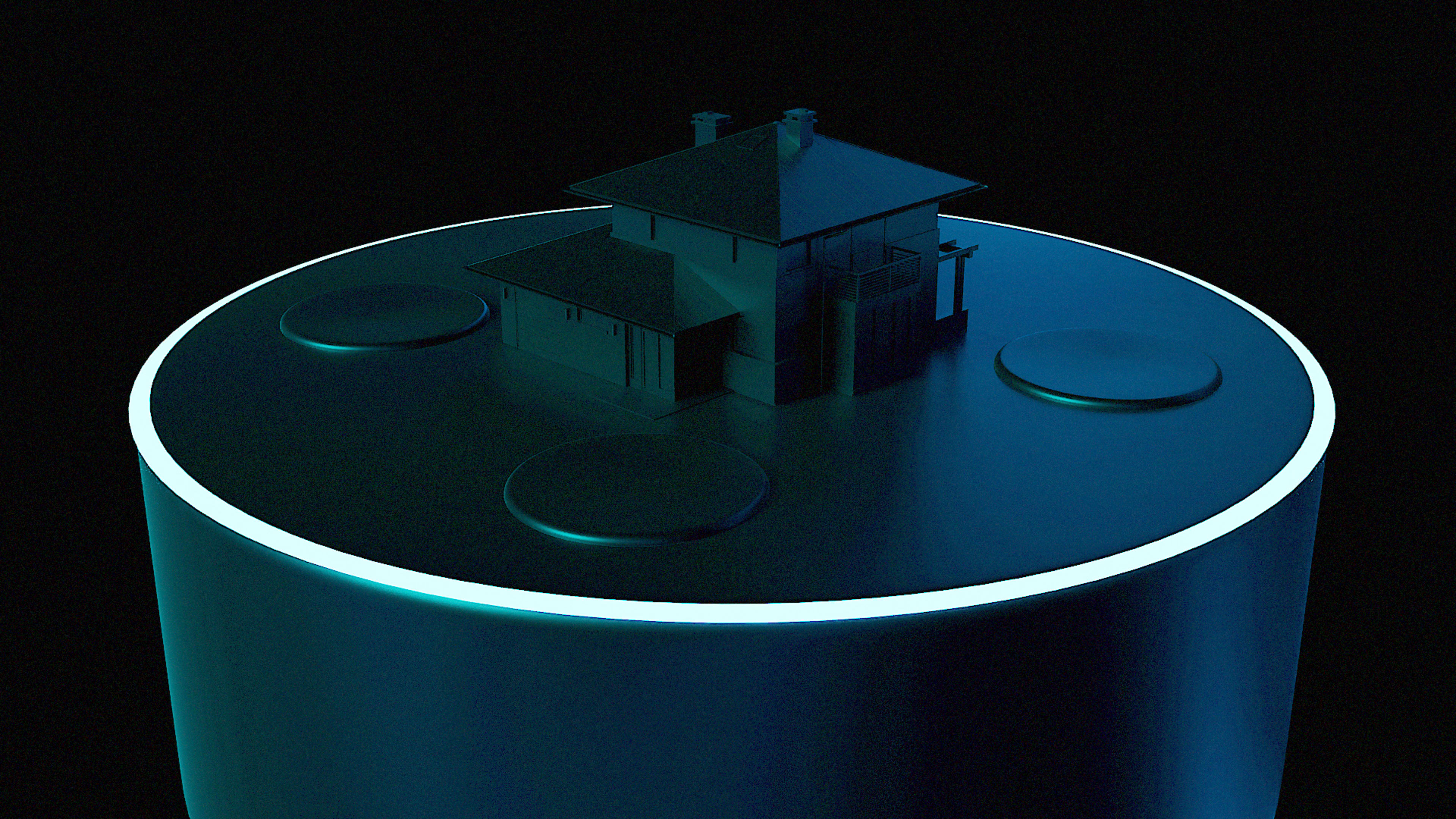

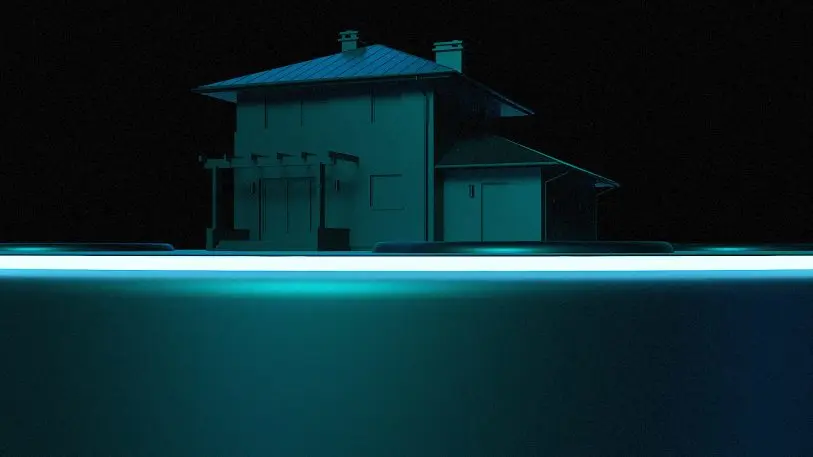

Webb, who authors a report called Emerging Tech Trends every year, believes that a series of trends are converging on a vaguely dystopian scenario: “Your smart home is a smart prison and there is no escape,” she described at the South by South West conference in Austin earlier this month. “You can unplug your microwave, but you can’t unplug your whole family from the system.” That means that your life will become even more dependent on a large tech company–so much so that you won’t be able to escape the operating system that you’re living inside.

According to Webb, this future is nearly inevitable. It’s a mix of three major factors. First, there’s a proliferation of smart home devices that are worming their way inside people’s homes: smart thermostats, smart toilets, smart blood pressure monitors, smart ovens, smart TVs, smart you name it. In 2018, Amazon debuted a smart microwave that you can talk to.

Second, the number of voice-activated devices is increasing rapidly, even beating analyst results: The total number of voice interface-powered devices increased 78% year-over-year, according to a report from NPR and Edison Research. As of January 2019, 53 million Americans own a smart speaker, and a staggering 8% of people in the U.S. received a smart speaker over the 2018 holiday season.

Why would you need to talk to your microwave? It might make your life slightly more convenient to say, “Alexa, heat up my popcorn.” But Webb thinks that the real reason is to help Amazon get more data about you and how you live. Even if you currently subscribe to popcorn refills from Amazon, the company loses all visibility once its package arrives at your home. But if it can convince you to talk to Alexa, the company can gain access to a whole lot more information. As soon as you ask Alexa to pop your popcorn, Amazon will get data about who is heating it up, and what time of day you like to eat your popcorn. But the company can learn more than that: From ambient noise, it may be able to detect who else is in the room and maybe even discern from your voice whether you’re sick or depressed, a technology that Amazon filed a patent for in 2018.

When your microwave–and any other device you’re talking to–begins to send data back to a corporation, that company gains more insight into how you and your family live. That might sound fine on its own. But Webb’s third major trend makes this idea more troubling: Amazon is getting into healthcare through a partnership with JPMorgan Chase and Berkshire Hathaway, and one of the company’s early investors speculates that “Prime Health,” Amazon’s version of the doctor, is already on its way. Google is getting into healthcare through the Alphabet company Verily and its Google Fit ecosystem for wearables. Apple is getting into healthcare through its on-site employee medical clinics, Apple HealthKit, and Apple Watch. In the context of healthcare, lifestyle data starts to be incredibly valuable. If you’re giving health data to a company that is also providing healthcare to you, whether that’s through primary care or insurance, that means the company could potentially use your lifestyle data to inform how much your healthcare should cost. If Amazon knows you eat popcorn every night before bed, will the eventual version of Prime Health cost more for you as a result? Or will it perhaps lock your garage to encourage you to walk to work instead of driving, because it thinks you need to exercise more?

The extent of companies’ grip over our homes is just beginning. In 2018, Amazon debuted a smart plug, a device that sits between your outlet and a non-connected device in your home and enables you to control that device via the Amazon smart home operating system. These smart plugs are laying the groundwork for a home operating system that only works with other Amazon products–a preview of the company’s ambitions to lock you into Amazon’s ecosystem, giving Amazon power over your home and everything in it. That idea is being built in full-scale smart homes as well. In 2018, Amazon partnered with Lennar, one of the largest manufacturers of houses in the country, to launch Amazon-powered connected homes, which are outfitted with cameras and sensors to offer a smart lock, smart security cameras, smart doorbell, and smart speakers all powered by Amazon–and there are likely more features on the way. In 2018, Lennar built about 35,000 houses in 23 states, all with Alexa built in.

Webb foresees Apple and Google eventually offering their own versions of the smart home, powered by their smart assistants, with their own suite of connected products (to be clear, neither company has announced connected homes, though both sell a suite of smart home products). These elements could be so deeply integrated into your home, whether you moved into a connected home or just voluntarily picked an operating system and started installing smart devices, that if you ever decide that you don’t like Google’s or Amazon’s or Apple’s data surveillance, changing your house’s OS would be incredibly difficult. In essence, you’d be locked in–unless you moved.

In an ideal world, all this home automation would make our lives easier, more efficient, and nudge us into healthier lifestyles. (And that’s certainly what the tech companies are selling.) But Webb isn’t convinced: The flip side of all that techno-optimism is that people have less and less choice over what tech they use and how they use it–all for the small, silly convenience of telling Alexa to pop your popcorn.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.