In 1989, when JamieSue Goodman was a high school freshman in Manning, South Carolina—population 4,000—her journalism teacher got a grant to buy a computer. The idea was to use it to lay out the school paper. But desktop publishing was new, and the teacher didn’t have a technical background. And so the whole experience turned into an adventure in discovering the machine’s capabilities.

“I had to learn how to use the computer alongside my teacher, everybody struggling together,” Goodman remembers. “And I loved it.”

Fast forward to 2019. Schools are full of computers, be they Macs, Windows PCs, Chromebooks, or iPads. However, a modern version of the situation Goodman encountered 30 years ago persists. Even gifted teachers aren’t necessarily prepared to guide students through using technology to accomplish real-world tasks.

And JamieSue Goodman is in a position to help. As project lead for Applied Digital Skills at Google, she spearheads an ambitious program to provide educators with a rich set of video-based instructional materials that they can access for free. “Basically, every job out there requires some basic computer skills,” she says. “And we want to make sure that everybody has what they need to succeed.”

Goodman didn’t set out to make education her life’s work. After majoring in English at the University of South Carolina, she pursued a career in computers and ended up in New York, where she worked on software for Zagat, the publisher of restaurant guides. When Google acquired Zagat in 2011, she became a Googler, eventually returning to South Carolina to work out of a company data center near Charleston.

A self-taught technologist and daughter of a fourth-grade teacher, Goodman found that she had a yen to give other people the kind of education that had taken her far beyond her small-town roots. “I wanted to teach students about digital skills through applying those skills to building awesome things,” she explains. Given that she worked at Google, which reaches 80 million people with its G Suite for Education and 40 million students and teachers with the Google Classroom class management service, she had the opportunity to satisfy that desire in a big way.

Along with Google colleagues, she created an initial curriculum, CS First and field-tested it in South Carolina schools. Following Goodman’s “awesome project” philosophy, it’s organized into activities that kids care about: A collection of athletic-themed lessons, for instance, includes such tasks as recording sports commentary, making a commercial for a fitness gadget, and programming an extreme sports game.

After launching CS First in 2014, Goodman and her colleagues went on to develop the Applied Digital Skills curriculum, which debuted for the 2017-18 school year. Its broader scope helps students prepare for life beyond the classroom, showing them how to create a résumé in Google Docs, organize college information in Google Sheets, assemble a presentation in Google Slides, and even analyze data to predict hit movies.

Applied Digital Skills includes more than 90 hours of video as well as supplemental materials such as instructor guides and a dashboard that lets teachers monitor each student’s progress. Projects range from 45 minutes to 10 hours in completion time; most are aimed at middle and high school students, but some are appropriate for late elementary school students and adult learners. Since it launched, 360,000 students—both K-12 and adult learners—have used the materials and 50,000 teachers have registered.

Google isn’t the only technology provider with free curriculum materials that can help schools get the most out of its products: Apple, for instance, offers “Everyone Can Code” and “Everyone Can Create” lessons centered around the iPad and Mac. Applied Digital Skills immerses students in Google tools such as Docs and Spreadsheets, but Goodman says that it isn’t part of a hard sell to get schools to choose Chromebooks over competitive devices. Everything is equally applicable to classrooms with Windows PCs or Macs.

Though Google planned all along to give its lessons plenty of flexibility to meet the needs of different classrooms, Goodman says that she’s continually inspired by just how inventive teachers get with them. “We saw all of these teachers who were tweeting about using our materials in the English language arts class,” she says. “Someone took an if-then adventure story unit that we did and turned it into an adventure with viruses and medications for their science class.”

As teachers bring their own approach to the Applied Digital Skills materials, their discoveries shape the curriculum’s future. “They give us so many ideas,” says Goodman. “They’re always sending in emails with suggestions about things to add, things to change, places where their kids got stuck.”

One of those helpful folks is Amanda Alford, a seventh-grade science teacher for the Switzerland County school district in rural Indiana. “JamieSue and the crew definitely listen to what people are asking for,” she says, adding that if Google adds a unit on how to become a YouTuber, “I have about a hundred 12-year-olds who would be eternally grateful.”

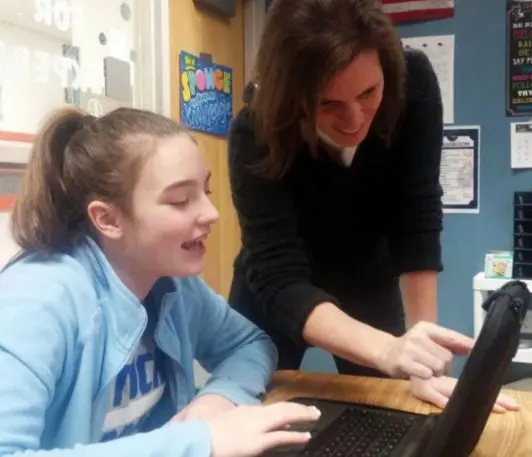

For Alford, Applied Digital Skills is in part about the four Cs that will boost her students’ prospects when they enter the job market: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity. But she says that there’s a fifth C where it might be most valuable: confidence. She recounts a recent moment in her class as students tackled an Applied Digital Skills lesson involving creating an interactive guide to a local area. The project required some coding, which left one girl fumbling a bit and looking frustrated. And then she figured it out.

“My student jumped up and started just doing this happy dance in the middle of class,” Alford says. “She sat back down and had the biggest smile on her face. I said, ‘How do you feel now?’ She goes, ‘I’ve got this.'”

Such moments aren’t just epiphanies for Alford’s seventh-graders; they’ve also led her to reassess how she teaches even when she’s not using Google’s materials. “This is how students learn now, not like 20 or 30 years ago, sitting in the rows with a pencil and a worksheet,” she says.

In other words, Alford is learning alongside her kids, connecting the dots back to when Goodman and her journalism teacher unlocked the potential of her school’s PC 30 years ago. That shared odyssey—as much as any specific skill—is why Google’s curriculum can be such powerful stuff.

This article was also published at The74Million.org, a nonprofit education news site.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.