In the not-too-distant future, industrial plants might start turning captured CO2 back into coal–and as old coal mines shut down, they could turn into storage vaults for the new product. Machines could shovel coal inside instead of taking it out, in a process that researchers say is something like “rewinding the emissions clock.”

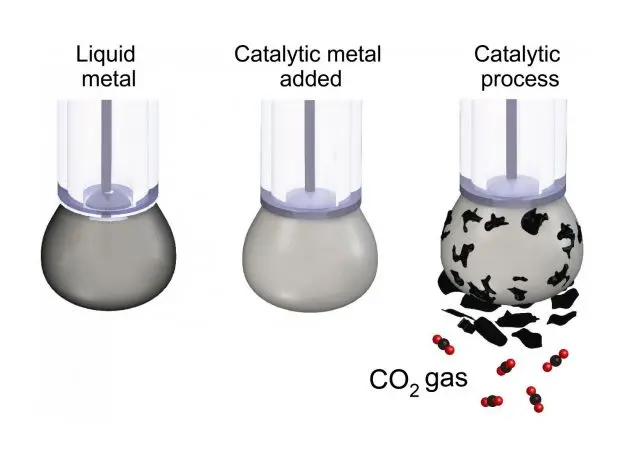

In a lab at RMIT University in Australia, researchers demonstrated the basics of the new process for the first time. Using liquid metal and electricity, dissolved CO2 transforms into solid flakes of carbon. The process could be used in combination with new machines that suck CO2 out of the atmosphere.

“The assumption is that we’ll have to do something like that in the near future,” says Torben Daeneke, a senior lecturer at RMIT University, and one of the authors of a new study about the technology. “I think the consensus is coming now that at some point in the next few decades, once we have conditioned our energy landscape toward green and sustainable energy sources, we will actually have to clean up our atmosphere and take the CO2 back out and do something with it to stabilize our climate.” While some environmental activists are skeptical, U.N. climate models assume that this type of “negative emissions” technology is necessary.

If CO2 turns into a solid, it can be safely stored. But past processes have required such high temperatures that they weren’t industrially viable. The new process can happen at room temperature. It still takes large amounts of energy; it isn’t possible to circumvent basic laws of physics, and you need to put in as much energy as was created when coal was first burned to create the CO2 in the first place. But the process can run on renewable energy. The basic technology is similar to the classic high school science experiment of using electricity via wires to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. In this case, instead of wires, the researchers use a liquid metal designed to efficiently split CO2 into carbon and oxygen.

The research is at an early stage, but promising. “We don’t see any fundamental reasons why this cannot be upscaled and rolled out on a mass scale,” says Daeneke. “We are working at the moment on upscaling and designing prototype devices and reactors to do this in the most efficient and cost-effective way.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.