When it comes to the debate over online content, Facebook, Google, Twitter, Comcast, and Verizon get a lot more attention than Cloudflare. But the San Francisco-based content delivery network and cloud security provider is growing fast and gaining notoriety for a nearly absolutist free-speech ethos that benefits everyone from human rights activists to white-power and Islamist hate groups.

What is Cloudflare? On an existential level, that question is central to the debate about its responsibilities online. In technical terms, it competes with companies such as Akamai by helping millions of websites negotiate the freewheeling internet, routing the sites’ traffic through a network of 165 data centers in 76 countries, to deliver it faster. Cloudflare also shields clients from attacks, such as the data-packet onslaught called a distributed denial of service (DDoS).

Cloudflare claims to support over 12 million web domains, including companies like Zendesk and Udacity, government agencies like the Library of Congress–and a handful of vitriol-spewing sites like The Nation of Islam and the Westboro Baptist Church (at the URL godhatesfags.com).

As a result, it’s incurred the wrath of hate speech watchdogs like the Anti Defamation League (ADL) and the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). When it stopped serving the white supremacist, harassment-inciting Daily Stormer in August 2017–the single client Cloudflare says it has ever dropped due to “political pressure”–it framed the move as a cautionary tale that it hopes to never repeat.

“Literally, I woke up in a bad mood and decided someone shouldn’t be allowed on the internet. No one should have that power,” CEO Matthew Prince wrote in an email to staff.

“If you do believe–as we do–that the edge of the internet of the future gets controlled by about 10 companies,” says Prince. “If those 10 companies start to impose the values of their leadership on what the internet looks like, I just think that that’s an incredibly risky thing to be doing.”

Cloudflare (which Fast Company named a most innovative company in 2012, 2018, and 2019) does have a shot at joining that group of 10. Launched in 2010, it reports serving nearly 10% of global internet requests. And it’s rumored to be prepping for a $3.5 billion IPO. (Cloudflare declined to comment on any plans to go public.)

The big debate is over where Cloudflare sits amid all the “layers” of the internet. If it’s down at the bottom, along with undersea cables and internet service providers, it arguably has a duty to keep the web free by allowing all the bits to flow. If it’s considered a content host or provider–more like YouTube or Facebook–there is a stronger but still contentious argument to make that it bears some responsibility for the effect that such content has on society.

Given Cloudflare’s growing market power and outspoken leadership, it’s a powerful test case amid the ongoing debate over the responsibilities of tech giants for the content to which they provide a platform. It could set a precedent for the “de-platforming” battles that follow.

One thing both sides agree on is that Cloudflare has worked hard to make its case to the world. “I think they definitely have been more visible,” says Keegan Hankes, senior research analyst at the SPLC. “I went to [international tech and human rights conference] RightsCon last year and heard Matthew Prince talk about this at length.

“But . . . at least when it comes to hate groups and Cloudflare, our position really has not changed,” says Hankes, “despite the fact that Cloudflare is doing more outreach to explain how it sees its role.”

The objectively good

The Cloudflare debate is a complex one, given its many laudable achievements.

In 2014, for instance, it launched Project Galileo, which provides free security services for sites under threat of cyberattack for their news reporting, political speech, or artistic expression. In late 2017, Cloudflare launched the Athenian Project, which provides free hacker protection to U.S. election authorities.

Last April, it teamed with the nonprofit Mozilla Foundation (maker of the Firefox browser) to introduce a free encryption service that makes it harder for ISPs, hackers, or snooping governments to track where people go online. (It encrypts the traffic to the servers that web browsers or apps contact in order to translate a site’s text URL, such as “google.com,” to its numerical IP address, like 172.217.7.196–taking away an easy web-surfing roadmap for snoops.)

This is just a subset of public benefit services the company has offered and continues to roll out.

“Cloudflare does care substantially about not just civil liberties but human rights,” says Brittan Heller, a former Department of Justice attorney on human rights and cybercrime and former director of technology and society for the ADL.

“I think that for them the question is, ‘If we have the ability to reshape the whole internet, when do we use it and how?’ And I think for them the answer is, very sparingly,” says Heller, now an adviser on human rights and technology for governments, tech companies, and civil society groups.

Repulsive bedfellows

Even as it continues to win plaudits for its good deeds, Cloudflare is regularly shamed for enabling repulsive groups by helping them provide a better internet experience to their followers.

In October 2018, Cloudflare stood out by continuing to support the chat platform Gab–infamous for racist chatter, including a post by Robert Bowers, who was charged with murdering 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue on October 27. Infrastructure companies like hosting provider Joyent and domain-name registrar GoDaddy dropped the site. But Cloudflare held on and continues to support Gab.

In December, a Huffington Post article reported that the company serves at least seven groups on the U.S. State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations, including al-Shabab, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), al-Quds Brigades, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, and Hamas.

If true, that would go beyond standing up for freedom of speech. It could be a violation of U.S. law that forbids “material support or resources” to such groups, the article asserts.

“Cloudflare is committed to complying with our legal obligations, including the sanctions programs overseen by the Office of Foreign Assets Control at the U.S. Treasury Department,” Kramer wrote in a follow-up email to our meeting.

But the company places the onus to act on government authorities. “Any law enforcement requests that we receive must strictly adhere to the due process of law and be subject to judicial oversight. It is not Cloudflare’s intent to make law enforcement’s job any harder, or easier,” says the latest transparency report about inquiries from law enforcement agencies.

As for the sites mentioned in the article, Kramer writes, “I want to make it clear that we’ve never been approached by the DOJ or Treasury about anything covered in the Huffington Post article.” He does not address whether the sites use Cloudflare, writing, “As a security company, we cannot discuss individual sites or entities.”

Legal or not, a handful of groups on Cloudflare’s network are not only distasteful but also potentially dangerous. “I know that frequently when we’re talking about content issues, this can become muddled in terms of: Well, what is offensive content?” says Joshua Fisher-Birch, a content review specialist with the nonprofit, nonpartisan Counter Extremism Project (CEP). “We’re focusing on the worst-of-the-worst content here, which is specifically terrorist organizations, which is specifically extremist organizations that explicitly want to cause violence.”

CEP has sent letters to Cloudflare since February 13, 2017, warning about clients on the service, including Hamas, the Taliban, the PFLP, and the Nordic Resistance Movement. The latest letter, from February 15, 2019, warns of what CEP identified as three pro-ISIS propaganda websites.

“When we receive notices of this kind, we direct individuals and organizations to file abuse complaints through our general abuse process. If we determine that a complaint is legitimate, we take appropriate action,” Doug Kramer tells Fast Company. Cloudflare would not comment on any of the sites, but the Hamas, PFLP, and English-language Taliban sites no longer appear to be on Cloudflare.

Keegan Hankes provides the example of U.S.-based Cloudflare client SiegeCulture. It’s associated with the group Atomwaffen (atomic weapon) Division, which both SPLC and the Anti Defamation League (ADL) label as a neo-Nazi organization bent on race war. (We contacted the ADL, but they were not able to provide a spokesperson in time for this article.) In the past two years, current or former members of Atomwaffen Division have been tied to several murders and alleged terrorist plots.

“We are opposed to the Atomwaffen Division having a web presence,” says Fisher-Birch.

One charge that can’t be made is that Cloudflare puts profits ahead of values. Larger clients do pay for its services, but small sites generally qualify for its free tier of service. And fortunately, most hate sites don’t have big followings. Prince says that the “vast majority” of problematic sites have free accounts. “This isn’t a decision that we make because it’s a financial decision,” he says.

Cloudflare’s policies seem genuinely motivated by philosophy. Prince regularly cites thinkers including Aristotle, Emanuel Kant, and James Madison in explaining how the company decided on its content strategy. (Kramer, a veteran of the Obama White House, has an undergraduate degree in philosophy.)

“There are plenty of days that I wake up and I think, Gosh, you know, there’s this wrong in the world, and I sit in a position to be able to impose my will on it,” says Prince. “But I think that’s a really dangerous thing because, who elected me? Who put me in a position to be able to do that?”

What’s Cloudflare’s place in the internet?

Prince may overstate his power. Cloudflare can’t actually kick someone off the internet, a point it makes in describing its limited role to critics. Dropping a site would just make it slower, since it wouldn’t have Cloudflare’s optimization services.

That’s good enough for Keegan Hankes. “I don’t want terror manuals being optimized for content delivery across their networks. I think it’s a negative for society,” he says. “I would also imagine that the families of that group’s victims will think that that’s a negative for society as well.”

Hankes agrees with the argument that companies operating the “pipes” of the internet, such as ISPs, shouldn’t filter content. He just doesn’t consider Cloudflare one of those pipes–or not solely a pipe company. For instance, to optimize a site’s content delivery, Cloudflare has to cache copies of their material on its servers around the world. Hankes calls that being a content host.

If a site could be online even without Cloudflare, is the company really part of the internet pipes? Perhaps. While not technically essential to the internet, content delivery networks like Cloudflare or Akamai, or Netflix’s own dedicated system are key to keeping the internet running smoothly.

While Cloudflare can’t knock a site offline, removing its security services makes it easier for hackers to do so. And a web host provider that suffers continued attacks due to one client might be inclined to cut that client loose.

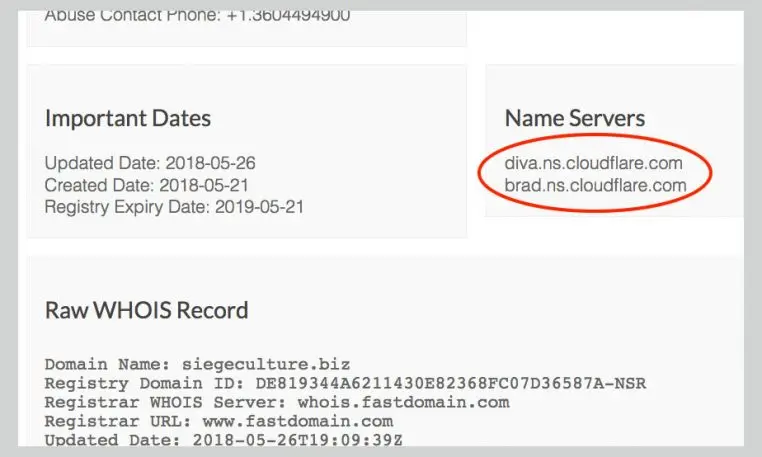

Removing Cloudflare also ends up revealing the identity of a site’s host provider, who often faces pressure to drop offensive sites. (With Cloudflare, the true host name is hidden from domain name searches using the WhoIs lookup service, allowing such sites’ enablers to avoid exposure.)

“Cloudflare is part of the architecture of the internet,” says Brittan Heller. “They speed up traffic, and they provide vital cybersecurity services to most of the internet.”

Cloudflare also opened a budget domain name registrar service last year, competing with companies like GoDaddy. Dropping a site’s registration is another way to kick it offline (which GoDaddy has done for controversial sites, such as Gab).

And the company is now hosting content–even by its own definition. Cloudflare runs a video-distribution service, for instance. This means Cloudflare could have different social responsibilities for different aspects of its business.

“What we do when we are simply mitigating a denial of service attack is different than when we are a caching an object and delivering it, says Prince, “which will be different than maybe if we were hosting a streaming video site. And the policies for each of those things should be different.”

In short, things are only going to get more complicated for Cloudflare as it branches into the new businesses it’s already announced and possibly others that are still on the drawing board. But Cloudflare has always been planning for a long game, says Prince, from before the company even launched.

“The test we would always put out was to say, if Cloudflare ran the entire internet, what would the right policy be?” says Prince. “And when it was three of us above a nail salon in Palo Alto, California, that was absurd. But today, when so much of the internet does flow through us, I’m glad that we made some of those decisions and did things that were really hard.”

But no matter how hard Cloudflare thinks about issues of free speech and its responsibilities to keep the internet moving, others may think differently. “We disagree with your position on hate groups,” says Keegan Hankes, “if you aren’t doing something to actively prevent hate groups from taking advantage of these platforms.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.