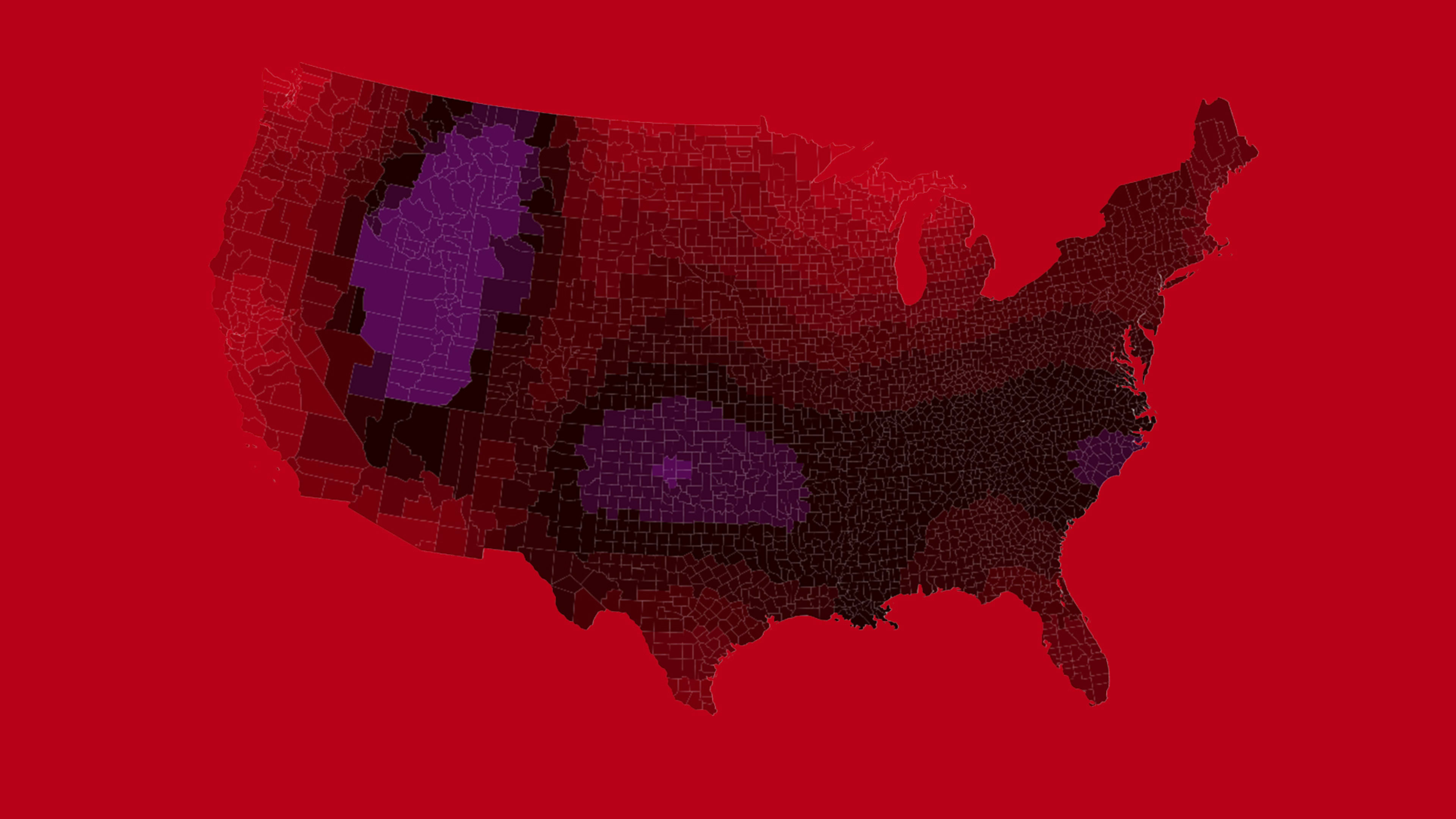

If you’re wondering where illness is spreading in the U.S. right now, the official CDC flu map might not be particularly helpful; it’s based on data that’s both delayed and not very local. Instead, try this new map that uses anonymous data from smart thermometers. When someone gets a fever, the data helps build a detailed picture of who’s sick.

“How do you curb the next epidemic if you don’t know where and when it’s starting? You can’t,” says Inder Singh, CEO of Kinsa, the company that makes the smart thermometers, now in use in nearly a million households.

Singh, who previously worked for the Clinton Health Access Initiative, started the company after seeing how governments work to curb the spread of infectious illnesses. “The sad fact is, we have almost zero accurate information about where and when disease is starting or spreading,” he says. “It’s all based on models that are pretty inaccurate.”

Other models use data including the sale of cold medicine–which comes with a delay, since people may have been sick for a few days before going to a pharmacy–or medical records, which are delayed even more, and don’t track the length of an illness. (Google Flu Trends, which tried to predict the spread of flu based on Google searches, shut down after missing the peak of the 2013 flu season.) Kinsa realized that technology could help gather better individual data, and decided to gather it through thermometers since that wouldn’t involve changing behavior. “We said, let’s give people a smarter, cheaper, better version of a product that they already use within hours of symptom onset,” Singh says.

Near the height of flu season, the company gets around 40,000 temperature readings each day. The thermometer comes with an app, which can gather more data about symptoms and then make recommendations about when to go to the doctor. In a pilot with one healthcare provider, the company found that the system made people more likely to avoid the emergency room when they didn’t need it, which in turn helps avoid infecting the most vulnerable people. Both the temperature data and data from the app also help track the spread of disease. The company has partnered with around 1,200 elementary schools to give away its thermometers to families, who can track a weather forecast-like map of disease at a specific school to know when it’s more likely that a child might have a more serious illness. Pharmacies are also using the data to keep drugs in stock. Ultimately, the company hopes the data will be used by public health agencies. Academic studies have shown that the results are as accurate as the CDC data, but available earlier and detailed down to the level of zip codes, not states. “It turns out that it works,” he says. “We see that we have the best data on where colds and flu are spreading.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.