It’s a seemingly small thing, but that red “NOT SECURE” warning that may pop up when you’re using Google’s Chrome browser was the product of hours of debate, design, and development to keep users safe.

Emily Schechter, a product manager who runs the security team that came up with this alert for users heading to non-secure sites, says it’s important to know how the web works if you’re going to use it. However, most people would be hard-pressed to define HTTPS, which stands for Hyper Text Transfer Protocol Secure. That is the secure version of HTTP, meaning all communications between your browser and the website are encrypted.

That was confirmed when Google’s researchers interviewed people across a swath of U.S. communities including rural Maine, a suburb in New Jersey, and Silicon Valley. Only about half could identify a secure connection from browser screenshots. “While not terrible,” the researchers wrote, “we hope that someday, more than half of users will understand how to differentiate secure and insecure connections.” What was more alarming was that all of the participants handed over their passwords when asked to log in to their bank over a non-secure HTTP. More secure HTTPS sites are on the rise, according to Google’s data. Schechter says there’s been a sharp increase to 80%, up from 30% in 2013.

Nevertheless, Schechter believes that security should be intuitive and nearly invisible–especially as malicious attacks continue to proliferate. Schechter is quick to point out that that’s not necessarily the product of more sophisticated hackers. “More services are coming online,” she notes, and more people are putting their information online, too she says. “At the same time, we are investing more in security,” she adds.

Parisa Tabriz, Google’s senior director of engineering at Chrome, agrees. She confesses that she didn’t grow up surrounded by technology, and many people in her immediate family are self-proclaimed luddites. “I get a lot of firsthand feedback about how confusing and unusable security solutions are from otherwise smart and well-intentioned individuals,” Tabriz explains, and it’s one major reason she does the work she does for Chrome and for Project Zero.

In the space of four years since it launched, the Project Zero team has reported more than 1,400 vulnerabilities in operating systems, browsers, antivirus software, password managers, hardware, and other popular software, Tabriz noted in a blog post.

“I don’t think it’s ever helpful to blame the user, and when I see people struggle, or worse, become victims, it motivates me to make security simpler and more automatic in the products we build,” Tabriz says. “People shouldn’t have stress about staying safe. That’s our job.”

This is why Schechter, Tabriz, and others are working to simplify security. For example, the lock symbol seems like a given now, as it’s been widely deployed to denote that a website is secure. Google’s researchers noted that it was best to leave well enough alone. “Making major modifications to this [lock] symbol, such as using a different object, may be disorienting: Users now expect to find a lock in a browser window,” they write.

The research also compared Chrome and Firefox. Firefox’s two lock icons have different meanings: a green lock for HTTPS, and a gray lock with a small yellow triangle for HTTPS with minor errors. Chrome similarly has two locks: a green lock for HTTPS, and a red lock with a slash for HTTPS with major errors. They’re both pretty close, especially when seeing them at small scale, like on a mobile browser. Chrome, they noted, can be problematic because it uses colors that colorblind people commonly cannot distinguish, but they kept them anyway.

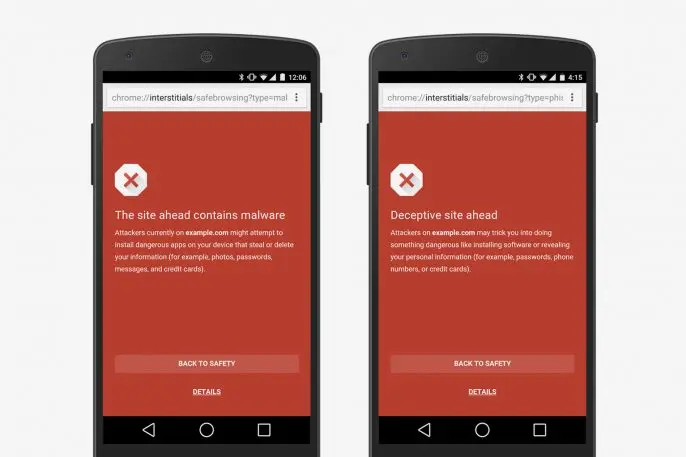

“Google also tested variants of the wording on the warnings,” says Schechter. The hypothesis was that one of the variants would do better than the control. For instance, the control was, “The website ahead contains malware!” and the variant said the same thing, but added, “Go back!” Schechter says they found that the wording variants didn’t make a difference that was meaningful. “This surprised us,” she says.

Tabriz says the Chrome teams take their role as leaders in this space “really seriously,” and that means sharing knowledge and best practices for everyone. For children who are growing up now, never having known a world without the internet, Tabriz says she sees this as a shared responsibility between many different groups across the private and public sectors.

“Technology companies have an important role to play, and that’s part of the reason we kicked off a program called Be Internet Awesome, which provides resources like online games and lesson plans so that kids, teachers, and parents can all learn to be safe online together,” Tabriz says. They also have ongoing online safety workshops for users around the world.

Schechter says that other safety precautions to keep in mind are pretty basic, including installing software updates when prompted. “It’s one of the best things you can do since [software developers] typically release security patches with every update,” she explains, adding that Chrome now features automatic updates.

Tabriz points out that users often know about the importance of creating strong passwords with unique characters and of a certain length, but they often don’t realize how important it is to have unique passwords for each website. “Using the same password across multiple accounts is like using the same lock and key to multiple houses,” Tabriz maintains. “It increases your risk.”

More than half of people (52%), according to Google’s research, reuse the same password for multiple (but not all) accounts, and only 24% use a password manager. To that end, both she and Schechter recommend using a password manager to automatically generate and manage all your passwords. “Chrome has one built in by default,” says Tabriz.

Although this facilitates certain security measures, critics of the Chrome browser warn that its privacy settings default to sending users’ data back to parent company Google to further generate ad-based revenue. Fast Company’s Katharine Schwab recently reported that one of the latest updates to Chrome automatically logs users into the browser whenever they’re logged in to any other Google service such as Gmail or YouTube.

“This basically eliminates the possibility for you to use Chrome and a Google account without the two being integrated, eroding another element of the browser that lets you keep your internet activity separate,” Schwab says.

Tabriz counters with the fact that Chrome’s goal is to be completely transparent with its users about what data they collect and why. “Users have control via settings to make changes to suit their personal needs or just turn it off,” she says. Browsing history or location data is supposed to function as a tool to make more relevant and personalized suggestions that make navigation and searching faster and easier, she says, and this can also be turned off. “We describe this and more in detail in the Google Chrome Privacy Whitepaper,” she says, “and want to give users control so they can make the right trade-offs for themselves.”

The teams are the reason for these developments and the thought baked into the design. “I can’t speak for all female engineers,” Tabriz notes, “and Emily [Schechter] and I certainly have different skills and life experiences we bring to our team, but I do think that diversity of perspectives is critical to building the best solutions.” Tabriz believes that when it comes to keeping the world safe from a huge range of threats people face online, “we need as much diversity in perspective as we can get.”

Ultimately, Schechter says these teams are and should be responsible for doing the heavy lifting. “People should not need to be security experts to be safe online,” underscores Schechter. “That is why our work is important.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.