To seek the origins of Microsoft’s interest in artificial intelligence, you need to go way back–well before Amazon, Facebook, and Google were in business, let alone titans of AI. Bill Gates founded Microsoft’s research arm in 1991, and AI was an area of investigation from the start. Three years later, in a speech at the National Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Seattle, then-sales chief Steve Ballmer stressed Microsoft’s belief in AI’s potential and said he hoped that software would someday be smart enough to steer a vehicle. (He’d banged up his own car in the parking lot upon arriving at the event.)

From the start, Microsoft Research (MSR for short) hired more than its fair share of computing’s most visionary, accomplished scientists. For a long time, however, it had a reputation for struggling to turn their innovations into features and products that customers wanted. In the ’90s, for instance, I recall being puzzled about why its ambitious work in areas such as speech recognition hadn’t had a profound effect on Windows and Office.

Five years into Satya Nadella’s tenure as Microsoft CEO, that stigma is gone. Personal determination on Nadella’s part has surely helped. “Satya is–let’s put it very positively–impatient to get more technology into our products,” says Harry Shum, Microsoft’s executive VP of artificial intelligence and research. “It’s really very encouraging to all of us in Microsoft Research.” That’s a lot of happy people: more than 1,000 computer scientists are in MSR’s employ, at its Redmond headquarters as well as Boston, Montreal, Beijing, Bangalore, and beyond.

CEO determination, by itself, only goes so far. Microsoft has gotten good at the tricky logistics of identifying what research to leverage in which products, encouraging far-flung employees to collaborate on that effort, and getting the results in front of everyone from worker bees to game enthusiasts.

For the record, Shum argues that Microsoft’s old rep for failing to make use of its researchers’ breakthroughs was unfair–but he doesn’t deny that the company is much better at what he calls “deployment-driven research” than in the past. “The key now is how quickly we can make those things happen,” he says.

Judging from my recent visit to its campus, Microsoft is making things happen at a clip that’s only accelerating. I talked to Shum and some of his colleagues from across the company about the process of embracing AI as swiftly and widely as possible. And it turned out that it isn’t one process but a bunch of them.

Meeting of the minds

On the most fundamental level, ensuring that Microsoft AI innovations benefit Microsoft customers is about making sure that research and product teams aren’t siloed off from each other. That means encouraging teams to talk to each other, which Microsoft now does in a big, organized fashion. Every six months or so, for instance, an event called Roc is devoted to cross-fertilization between research efforts and Office product development.

“We have those two-, three-day workshops where we have 50 people from Microsoft Research, 100 people from Office, all coming together,” says Shum. Everybody shares what they’re working on, and the whole affair ends with a hackathon.

Of course, getting people talking about problems and solutions is just the beginning. The potential for AI to improve everyday Microsoft Office tasks such as formatting a document or plugging data into a spreadsheet is enormous. But it’s also easy to see how automated assistance could feel intrusive rather than helpful. Exhibit A: Office 97’s Clippy assistant, which remains a poster child for grating, unwelcome technology.

More than a decade after Office eradicated Clippy, it still wants to detect if you’re performing a task where AI might be useful. It just wants the experience to be subtle rather than intrusive. As Ronette Lawrence, principal product planning manager for Office, says, “One of our core principles is making sure that the human stays the hero.”

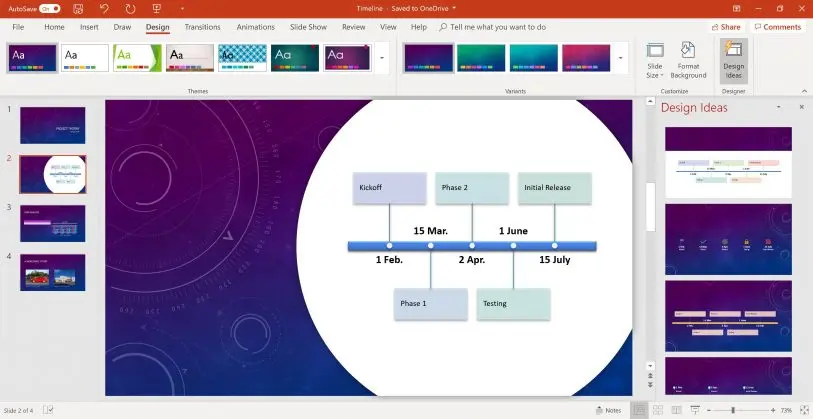

Lawrence says that nearly everything Microsoft is adding to Office these days has an element of AI and machine learning to it. In PowerPoint, for instance, the company wants AI to be “the designer that works in the cloud for you.” If you’re using a pen-equipped PC such as Microsoft’s own Surface, PowerPoint can convert your scrawled freehand words and shapes into polished text blocks and objects. And if the software notices that you’re entering a sequence of dates, it will realize that it might make sense to lay them out as a timeline.

Instead of shoving unsolicited advice in your face, however, “we’re careful to make sure that these kind of suggestions come out as a whisper,” says Lawrence. The “Design Ideas” feature analyzes your presentation in process and shows thumbnails of possible tweaks–such as that timeline layout for a sequence of dates–to the right of your slides. They’re equally easy to implement or ignore.

Though many Office features are dependent on Microsoft Research’s latest work, certain brainstorms make their way out the lab more easily than others. “Some of it feels like science fiction,” says Lawrence of AI in its raw form. “And other [examples] feel closer to product readiness.”

During one workshopping session between the Office product team and MSR, the fact that people typically rough out Word documents and fill in holes later–or ask coworkers to do some of the filling–came up. What if Word helped wrangle the process?

A new to-do feature aims to do that by scanning a document for placeholders such as “TODO: get latest revenue figures” or “insert graph here” and listing them in a sidebar so you remember to take care of them. Microsoft plans to extend the feature so that your colleagues can supply elements you’ve requested by responding to an email rather than rummaging around in your document. It also intends to use AI to suggest relevant content.

The first Office users to get access to this to-do feature in its initial form are Windows and Mac users who have signed up for Office’s early-adopter program. (It’s due for general release by the end of the year.) Oftentimes, however, new AI functionality shows up first in Office’s web-based apps, where it’s easier for Microsoft to get it in front of a lot of people quickly–and learn, and refine–than if the company needed to wait for the next release of Office in its more conventional form.

“It’s pretty important for us to listen to feedback and see how people are using it to train a model,” says Lawrence. “That is part of the new era of Microsoft, where it isn’t just about the usability of the functionality when you release it. The web gives us that feedback mechanism.”

A current series of online ads is devoted to showing that the Office 365 service has an array of handy features that are absent in Office 2019, the current pay-once version of the suite. All these features leverage AI, but the ads don’t mention that. After all, the human is supposed to be the hero.

Changing the game

When did AI begin to have an impact on the video game business? If you ask Kevin Gammill, partner general manager for PlayFab at Microsoft, he’ll reach back four decades and bring up early computer-controlled opponents such as the flying saucers in Atari’s Asteroids arcade game. “I think AI has been around as long as gaming’s been around,” he says.

That includes useful stuff that makes life better for game players without screaming “Hey, artificial intelligence!” Studies, for instance, have shown that online competition greatly benefits from players being matched with others of roughly comparable skill. “If you go into a game and you just get slaughtered, it’s probably not a good experience,” explains Gammill. “If everyone’s too easy, it’s also probably not a good experience.” Xbox Live has long used an algorithm called TrueSkill (recently updated as TrueSkill 2) to help ensure that contestants are neither bored nor massacred by their opponents.

Another piece of practical AI was inspired by the fact that Microsoft “heard for years loud and clear from gamers that they would greatly prefer to spend a lot more time playing games than downloading games,” says Ashley McKissick, who manages the Game Pass service. The company initially tried to let players skip ahead to the action before a download was complete through a system that required some heavy lifting on the part of game publishers and was therefore not universally adopted.

Starting last summer, Microsoft replaced this unsatisfactory handwork by humans with a piece of AI-enhanced technology called FastStart. It leverages machine learning to determine which bits of a game to download first, allowing gamers to begin playing up to twice as fast. “We’re not really changing the laws of physics here, but it does make your download much smarter,” says McKissick.

Increasingly, Microsoft is formalizing the kind of collaboration that helps AI make its way into games. Similar to the MSR/Office meeting called Roc, a confab called Magneto is designed to cultivate conversation–and outright hacking–between MSR and the gaming group. Along with those two constituencies, “there are people from Bing there, there are people from Windows there, there are people from Azure there,” says Tamir Melamed, Microsoft’s head of PlayFab engineering. “Because there’s a lot of those technologies that we think we can share down the road.”

One joint project emerged from Microsoft’s annual companywide hackathon. In 2017, the gaming group was wrestling with the challenge of curating Mixer, a game-streaming service–in the same Zip Code as Twitch, but more interactive–which Microsoft had acquired in the form of a startup called Beam. “We found ourselves with a much larger volume of streams than we had anticipated,” says Chad Gibson, Mixer’s general manager. “And so we were trying to find, ‘How can we provide new, unique ways of allowing players of PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds or Fortnite to be discovered?'”

As long as gaming has its frustrations, AI should provide further ways to mitigate them. Recently, Gammill was engaged in heated competition in the Tom Clancy first-person shooter Rainbow Six Siege against three friends. Then one contestant’s internet connection choked. “Three of us are running around and a frozen character is standing there,” he says. And a frozen character can’t do much except be mowed down.

A better scenario would be if the game could use AI to determine that a player had gotten cut off, and then take temporary control of the corresponding character–and play in the same style as that person. “Now we’re very close to scenarios like that actually coming to fruition,” says Gammill.

The silicon factor

Steve Jobs was fond of saying that Apple was the only computer company that built “the whole widget”–not just software or hardware, but both, integrated so well that the seams of the experience start to fade away. In recent years, that philosophy has reached its ultimate expression as Apple has even designed its own iPhone and iPad processors and optimized them for running Apple software.

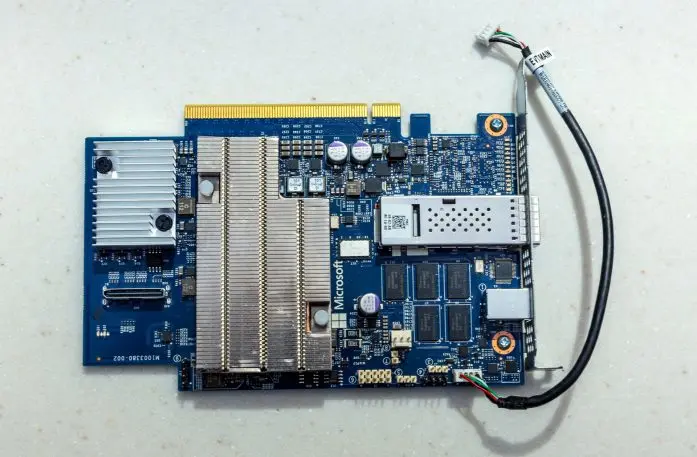

The same vertical integration that’s a boon for a smartphone or tablet makes sense, on a grander scale, for a data center–such as the ones that power Microsofts Azure services. Enter Project Brainwave. That’s the name for the custom hardware accelerator Microsoft has designed–using Intel field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs)–specifically for the purpose of speeding up AI running in the Azure cloud.

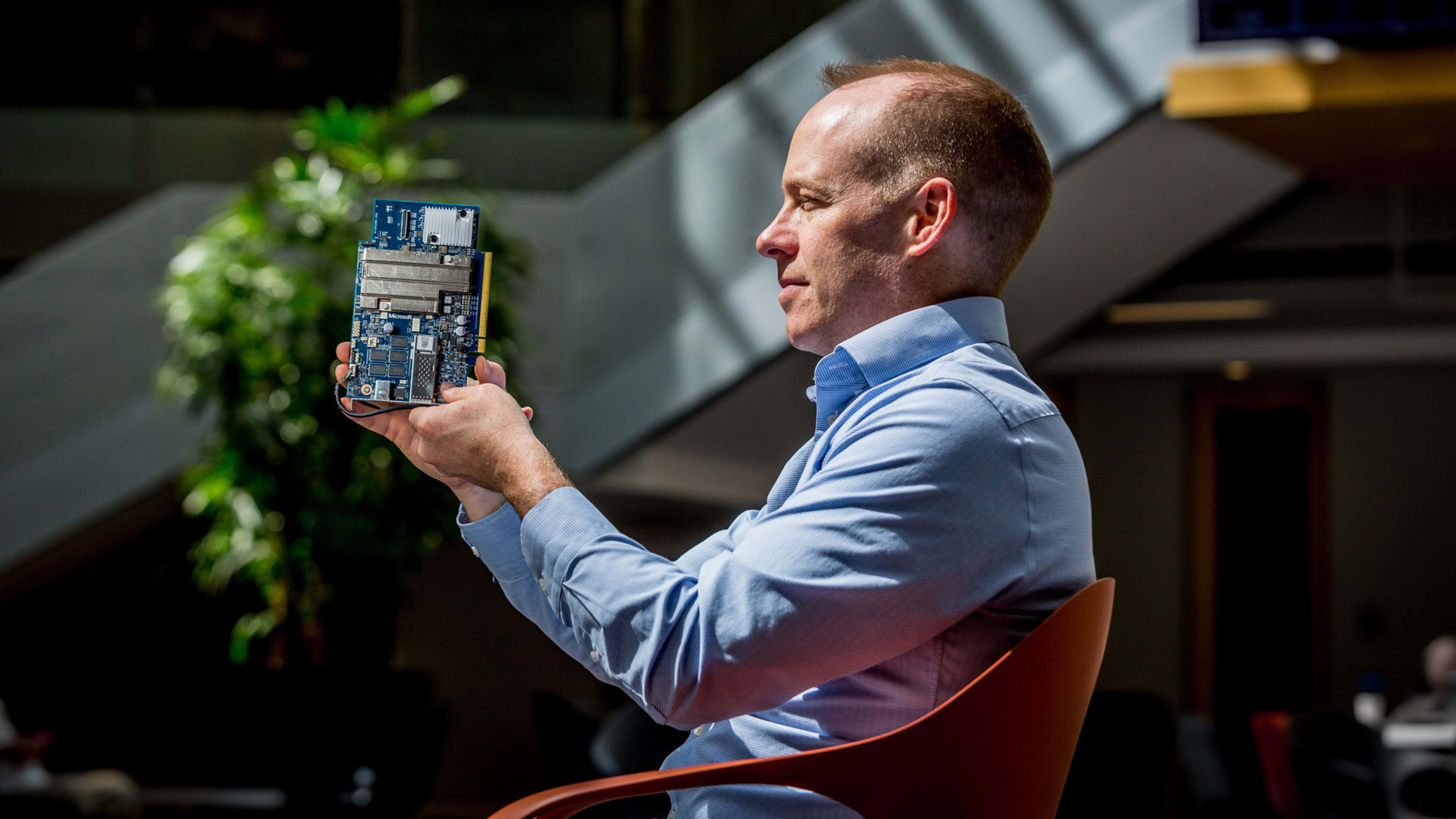

Microsoft’s move into designing its own hardware for optimal AI is hardly unique. Both Google and Amazon are also moving down the stack from software to silicon for similar reasons. But Microsoft isn’t just hopping aboard a trendy bandwagon. Project Brainwave is the end product of an opportunity Doug Burger began thinking about almost a decade ago–and at first, he did it on his own. “I started the work in 2010 and then exposed it to management after about a year,” remembers Burger, who was a researcher within MSR at the time.

FPGA technology allows Microsoft to deliver highly efficient deep learning as a service in a way that addresses specific customer requests. “A lot of the problems that they want to solve are around image analysis,” says Ted Way, senior program manager for Azure Machine Learning. “‘I want to look at my manufacturing defects.’ ‘I want to look at whether [products are] out of stock.’ ‘I want to see if people are smoking at my gas station because I’m afraid of fires.’ Doug’s team was able to turn that around and build these convolutional neural networks that ran super fast on the FPGA in just six months or so.” By silicon standards, that’s quick.

When Burger had begun his personal investigation of FPGAs in 2010, it wasn’t clear–at least to people who aren’t prescient computer scientists–how quickly AI would go mainstream, let alone that delivering it as a service would become a strategic imperative for a company such as Microsoft. Soon enough, Microsoft understood the value his brainchild could bring to Azure. Last July, after Project Brainwave left the lab, so did Burger and his team. Today, they’re continuing their work as part of the Azure group rather than MSR.

Such a segue is not unusual. “One thing about the Microsoft culture now, that boundary between research and product has blurred quite a bit,” says Burger. “The product groups have lots of people who were formerly researchers and are developing new stuff. Research has not only people that do research but engineers building stuff. It’s more of a continuum.” Nadella, he adds, “has done a great job of pushing down this kind of innovation.”

Self-serve smarts

With Azure, Microsoft is in a race with Amazon and Google to provide AI and other advanced computing functions to businesses of all sorts as on-demand services. That’s not just good for outside companies; there are also groups within Microsoft that can benefit from pre-packaged AI and machine learning.

Case in point: Codie, a multilingual chatbot designed to provide information about coding. An internal Microsoft experiment for now rather than a commercial product, it sprang from the realization that one major obstacle for would-be software engineers is simply having access to information about matters such as commands in the Python programming language and syntax for SQL database queries. The problem is especially acute for non-native English speakers.

Matt Fisher, senior data analytics manager for Office 365 and Microsoft 365, and one of Codie’s creators, describes the service as “Cortana’s geekier little sibling.” It emerged from the Microsoft Garage, a program that gives employees encouragement and resources as they pursue ideas they’re passionate about, whether or not they fit neatly into official responsibilities. Fifteen staffers with diverse backgrounds were on the team that created the service, including developers, designers, and marketers. It beat 767 other projects to win the company’s Redmond Science Fair, and took second place out of 5,875 entries in the company’s inclusivity challenge.

Though Codie’s creators brought a variety of skills to the enterprise, none of them started out knowing that much about AI. “We used out-of-the-box tools available as part of the AI Suite that Microsoft offers,” says Rahman. “And as devs we were able to pick up the documentation in no time and just get going.”

Fisher rattles off the Microsoft cloud offerings that power Codie: “We used everything from the Azure learning service to LUIS language understanding. QnA Maker, the Bing graph, the Microsoft graph, the Azure bot framework, the Azure speech plugin.” There was plenty of Microsoft AI expertise in there; it’s just that it was in ready-to-use form. For Codie–and many other things people want to build–that’s enough.

As an effort to leverage AI as an enabling technology for an inspiring purpose, Codie is already a success. The people who built it are thinking about upgrades–one obvious one would be to let users talk rather than type–and how to make it broadly available. “Our goal is that we would like to see it be used outside of Microsoft’s walls,” says Fisher. “We’re working towards what we need to need to do to get there. We have support from this lovely group, the Garage, but this is our second or third job in many cases.”

Real problems, real research

One other thing about Microsoft’s new approach to cross-pollinating research and products: It isn’t just the products that benefit. AI has an insatiable appetite for the sort of data required to train machine-learning algorithms. Microsoft, as one of the largest tech companies in the world, has that data, in anonymized form, by the metric ton. Which means that if there was a time when its research efforts benefited from being walled off from money-making businesses that serve actual human beings, it’s over.

“Nowadays, to do a lot of very exciting AI research, you need to get access to real problems and you need to get access to data,” says Shum. “This is where you work together with [product teams]. You build a new model, you train the new model, and then you tweak your new model. Now you have advanced your basic research further. And along the way, you never know–you could get a breakthrough.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.