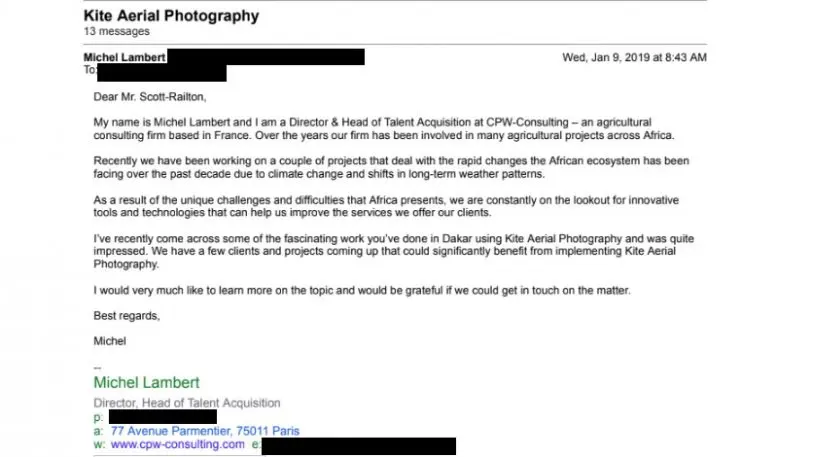

When John Scott-Railton got an out-of-the-blue email last month from someone who claimed to be an investor working on an agricultural project, he was immediately suspicious.

A researcher at cybersecurity watchdog group Citizen Lab, Scott-Railton is used to strange messages purporting to be from people they’re not. That’s how Citizen Lab’s most well-known research subject, the secretive Israeli company NSO Group, designed its sophisticated spyware to be delivered to unsuspecting targets’ iPhones: Click on this seemingly innocuous link, a random text message might tell you, and you’ll have no idea that your device and everything on it has just been owned by government-sponsored hackers.

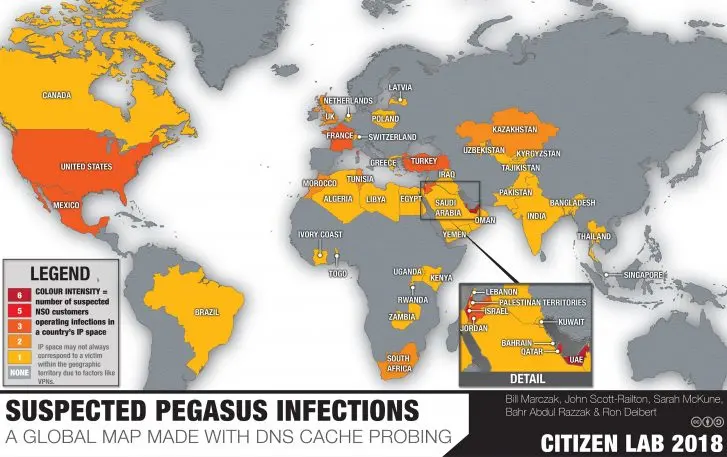

For three years, Scott-Railton and his colleagues at Citizen Lab have earned the ire of NSO and others for meticulously digging up evidence of the cyberweapon at work on the phones of dozens of dissidents, activists, and journalists across the Middle East, Uzbekistan, and other countries with dubious rights records.

The lab—made up of two dozen researchers, PhD students, and post-docs at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs—has been cited in recent lawsuits brought against NSO by a Qatari citizen, by Mexican activists and journalists, and by a Saudi friend of murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi, all of whom have been targeted by the spyware. Khashoggi was also reportedly a target of NSO’s weapons.

His suspicions raised, Scott-Railton decided he would turn the tables on the mystery man.

The sender, going by the name Michel Lambert, said he was a director at a Paris-based agricultural technology firm called CPW-Consulting, and regurgitated words and phrases from Scott-Railton’s personal website and LinkedIn profile. Eventually, he brought up flying kites, which Scott-Railton had mentioned on his website with a cheeky declaration of “I fly robotic kites in Africa.” For the cybersecurity researcher, it felt like someone was playing Mad Libs with his interests and experiences.

The timing of Lambert’s message also set off alarms.

Upon meeting, Bowman instead probed Citizen Lab’s years of research into NSO Group’s software and business practices, and attempted to get Razzak to make anti-Semitic or anti-Israel remarks. Citizen Lab quickly determined that Bowman’s company, the Madrid-based FlameTech, didn’t exist, which reporters at the Associated Press confirmed.

“Trying to give him all the pieces”

To Scott-Railton, the operation had all the hallmarks of private sector intelligence companies like Black Cube, which work for businesses to “help solve complex litigation challenges” under false pretenses, including fake identities designed to gather intelligence and compromise targets. Black Cube, which is based in Tel Aviv and London, has used undercover agents to approach women who had accused movie producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct, and dispatched operatives to probe Obama national security aide Ben Rhodes and another White House staffer involved with the Iran nuclear deal.

The spy’s ruse, Scott-Railton tells Fast Company, seemed terribly executed. Hoping to ensnare the bumbling spook, he indulged Lambert. In his reply, he played up the spy’s assumption that Scott-Railton was an enthusiastic but naive PhD student by sending Lambert a big email with links to papers and annotations.

“Lambert comes back at me and says, ‘Oh, that is very interesting, but I don’t have access to one of those papers, could you send it?” explains Scott-Railton. “Which, in my mind, was a standard intelligence tactic. You want to set up in someone’s mind the process of sharing documents and materials. So, I happily shared it with a bunch of extra stuff.”

A phone call followed, in which Lambert, a genial-sounding older man with a vague French accent, immediately, bizarrely, dove into French.

Up to that point, all communications had been in “word-perfect English.” Scott-Railton says he is bilingual, and he occasionally posts online materials in French, but it’s not a personal detail he typically broadcasts. Perhaps they were testing Scott-Railton to see if he was actually someone else. Or perhaps Lambert was just trying to appeal to Scott-Railton’s assumed enthusiasm.

After more conversation about kites and Africa, Scott-Railton helped Lambert get to the point: meeting in person, so they could discuss upcoming CPW projects and see if the researcher’s kite aerial photography expertise might be useful for his “clients.”

“And wouldn’t you know, he might be available to meet as soon as next week,” the researcher says.

Scott-Railton had decided to move all subsequent conversations and interactions to the United States in the hopes that if Lambert broke any rules, he’d be doing it on U.S. soil. Scott-Railton constructed an elaborate cover story about needing to meet in New York City, where he said he was searching for an apartment.

“During our phone call, he inquires about how the New York search is going, and the answer is, ‘Well, you know, not as well as I’d expect and it’s giving me some money problems,'” says Scott-Railton. “I’m just trying to give him all the pieces he needs to carry me on.”

After landing in New York on mid-January, Scott-Railton obtained a burner phone and submitted his new phone number, with his name and a New York address, to a number of people-finder websites. He also edited some old WordPress posts to include the burner number as his press contact, then created Craigslist posts and a Reddit profile, where he made public inquiries about New York City apartments.

On January 23, Lambert’s assistant, a man named Thomas Mbake, emailed with a location—the restaurant at New York’s five-star Peninsula Hotel.

Scott-Railton went to work developing an operational plan with the help of reporters from the Associated Press. Sitting nearby would be London-based AP reporter Rafael Satter, with a videographer stationed near the front door. Staked out across the street on Fifth Avenue would be a photographer with a telephoto lens. They wanted to be both inside and outside the spy’s surveillance periphery, assuming that Lambert would be there with his own team too.

Scott-Railton would also be wired, and not just for audio. The night before the sting, he stayed up late, armed with a pair of nail scissors, superglue, and a nanny cam, to turn the cannibalized lining of a hotel slipper into a necktie camera.

The conversation

Upon entering the restaurant, Scott-Railton didn’t immediately see Lambert. When the maître d’ escorted him to Lambert’s table, he said the spy seemed to suddenly pop out from behind a pillar that was obscuring him, almost like Boris and Natasha, the bumbling bad guys from the old Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons. Scott-Lambert found himself being ushered to a nice table by a window with his back to the rest of the restaurant. The maître d’ informed him that Lambert insisted he have a martini. “I’m thinking, man, he immediately wants me to start drinking.”

Scott-Railton had another thought soon after the meeting began: “I immediately noticed that another solo diner has plopped himself down at a table with a perfect view of me and the back of Michel, and is trying to unobtrusively take a picture with his cell phone but is looking obtrusive.”

And at various points during the meeting, he says, another unknown individual appeared at the dining room door.

Their conversation continues for just short of two hours, and it’s wide-ranging. For the first hour, Lambert regaled his unsuspecting-but-actually suspecting target with charming stories in French about his fictional life, including meeting African leaders, his love of cigars (specifically, the brand Punch), and his experience in the military with aerial photography and remote sensing. He also tried to get Scott-Railton to make racist remarks in French.

Eventually, Lambert, strangely, turned to cue cards, which he said he relied on to jog his memory. For the non-sensitive topics–background, getting to know Scott-Railton–the cue cards were green, and handwritten in English. When Lambert moved to the topic of Citizen Lab, he began using yellow cue cards. And when he started asking sensitive questions, the red cue cards showed up.

Listen to an excerpt of Scott-Railton’s conversation with “Michael Lambert”:

“It’s a pretty obvious way to do it,” Scott-Railton says. “The whole time he’s on sensitive topics he’s got this pen in his hand, which has an obvious hole in the top of its cap, so it’s either a microphone or camera, that he’s sort of holding pointed at me.”

“Right around the one-hour mark, after we’re well and truly introduced to each other, and we’d plowed the wagyu beef and lobster bisque on his side and then the salmon on my side, he pivots the conversation,” Scott-Railton recalls.

“‘Let’s talk more about your work’ . . . After basically pretending that he had no knowledge of my work, suddenly he has all these specific questions. He asks, ‘Are the people who are concerned with the abuse of spyware in Mexico, is there something anti-Semitic there?'”

Scott-Railton says Lambert’s conversational gambit was bizarre. The spy referenced a controversial novel about a Muslim kid and Jewish kid growing up in France. The Muslim kid eventually goes to jail, and when he’s released he returns to kill the Jewish kid. Lambert’s pivot was, “There’s a new kind of anti-Semitism now. Does that have anything to do with people’s support of your work in Mexico?”

Lambert also wanted to know if Citizen Lab was receiving money in exchange for its assistance in lawsuits against NSO. Another tack involved asking Scott-Railton what he thought about Edward Snowden’s allegation that Kashoggi’s cell phone might have been targeted by Saudi Arabia with NSO Group’s spyware.

Scott-Railton said he didn’t know, but Lambert persisted. “This is sensitive stuff,” the researcher said, half-teasingly. “We just met.”

Related: How Israeli spyware tried to hack an Amnesty activist’s phone

Several times Lambert tried to get Scott-Railton to repair to a cigar room, where they could enjoy a Punch cigar. To Scott-Railton, it all felt like someone who had done this many times. So many times, perhaps, that Lambert had grown too comfortable and complacent about the operation.

Scott-Railton poked his creme-bruleé and tried to draw as many questions out of Lambert as possible. Soon, the spy started asking the researcher probing questions about his family, which disgusted him. At this point, Scott-Railton received a text message on his burner: It was an AP reporter telling him that their recording devices’ batteries were about to run out, and that he needed to wrap things up.

“These are all scams,” he lamented, and showed Lambert a slew of texts supposedly linked to his real estate search.

“These are hackers,” said Lambert. “Be careful.”

Flustered, the spy stood up quickly, ran into a chair, and looked for an exit, only to linger for a bit after realizing he hadn’t paid the bill.

“The second layer was, could he get anything at all about Citizen Lab–any juice that wasn’t public,” he adds. “I keep throwing out these little softballs to him like ‘There’s lots of drama at Citizen Lab, a lot of personalities.’ And he’d say, ‘Oh, I like drama, tell me more,’ and I’d say, ‘Well . . . ‘ and he said, ‘Well, we’re on Broadway, so you should really tell me the drama.’ I look around and ask, ‘Are we really on Broadway?’ It’s really Boris and Natasha stuff.”

Listen to an excerpt of Scott-Railton’s conversation with “Michael Lambert”:

When Lambert’s operation went south, Scott-Railton says the spy did exactly the wrong thing. Instead of insisting that there had been some misunderstanding, that his company was small and seeking investment, Lambert stuck with the fiction, repeatedly insisting that the company was real.

Last week, the New York Times and Uvda, Israel Channel 12’s investigative program, reported that Lambert was actually Aharon Almog-Assoulin, a retired Israeli security official. Up until Tuesday morning, Almog-Assoulin’s WhatsApp profile picture was a photo of a cigar–Punch brand, of course.

“In the gray area”

It isn’t known who Almog-Assoulin was working for, but he turned up in an earlier case linked with Black Cube. A businessman in Toronto told the newspaper that in 2017 a person resembling Almog-Assoulin, using a different name, had asked him about lawsuits between two Canadian private equity firms. One of the companies has acknowledged that its law firm had hired Black Cube to help with its litigation.

Black Cube did not respond to Fast Company’s emailed requests for comment. In response to questions from the Times, the company threatened the paper with legal action and denied being part of the Citizen Lab operation.

As for the investigation into the person posing as Gary Bowman, the man who met with Citizen Lab’s Razzak at the Shangri-La, Scott-Railton said it’s hit a bit of a wall.

The larger issue, he said, is the industry of private intelligence companies. Hired to reduced risk for their corporate clients, he says they actually introduce some serious risks of their own.

“There is an industry that sells this kind of aggressive engagement that uses false pretenses . . . [and it] pitches itself as solving complicated challenges for businesses,” says Scott-Railton. “You can look at the website of a company like Black Cube, and you’ll see that they claim to solve the most complex litigation challenges. Well, in this case, I think whoever did this introduced one. This is a pretty complicated challenge for whoever the company is that did this, and that challenge might also be felt by its customer, whoever that customer is.”

Scott-Railton couldn’t say if his team was actively researching the company who employed Almog-Assoulin, but he did say that Citizen Lab is fully cooperating with all relevant authorities in all relevant jurisdictions.

“This is the kind of situation that, instead of discouraging researchers like us, renews our motivation–it renews our sense that we must be doing something right,” notes Scott-Railton.

He said the spy’s only specific questions about Citizen Lab’s work related to its research on NSO Group. But a spokesperson for the company told the New York Times that it had no link to the episode.

“NSO had absolutely nothing to do with this incident–either directly or indirectly. Furthermore, we did not hire Black Cube or anyone else to investigate Citizen Lab’s activities and we did not ask any person or organization to hire Black Cube or any other person or firm to investigate Citizen Lab,” the spokesman said. He said NSO is “quite familiar with Citizen Lab’s shoddy ‘research’ and its philosophical opposition to our work helping intelligence agencies fight terrorism and crime.”

The company, which is largely owned by Francisco Partners, a San Francisco private equity firm, says it complies with “applicable export control laws.”

Related: This powerful off-the-shelf phone-hacking tool is spreading

As Citizen Lab’s research has shown, powerful cyber-weapons and cyber expertise continue to proliferate beyond large governments like the U.S. and Russia. According to its findings, NSO’s spyware has appeared in 45 countries, and its targets have included an estimated 174 activists, journalists, and lawyers. Last week, Reuters reported that a team of former U.S. government intelligence operatives working for the United Arab Emirates had used a similar piece of spyware to hack into the iPhones of activists, diplomats, and rival foreign leaders.

To Scott-Railton, the time and money spent by the commercial spyware industry on promoting a narrative that it is ethical and built around supporting law enforcement, while it covertly seeks to undermine the work of Citizen Lab, suggests that the industry has a dark underbelly.

“It’s a side [of the commercial spyware industry] that is in the gray area of where there may be cases of illegal, criminal behavior,” he says. “What cases like this do is they suggest that that might be right. This is an argument that there is something with that industry, and that that industry is capable of behaving recklessly.”

“If the goal of that operation conducted against us,” says Scott-Railton, “was to suggest that Citizen Lab’s points were wrong, if anything, they’ve kind of made our point for us: that the industry may be a little bit out of control.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.